Luce deLire

Independent Scholar

I. A Case of Murder

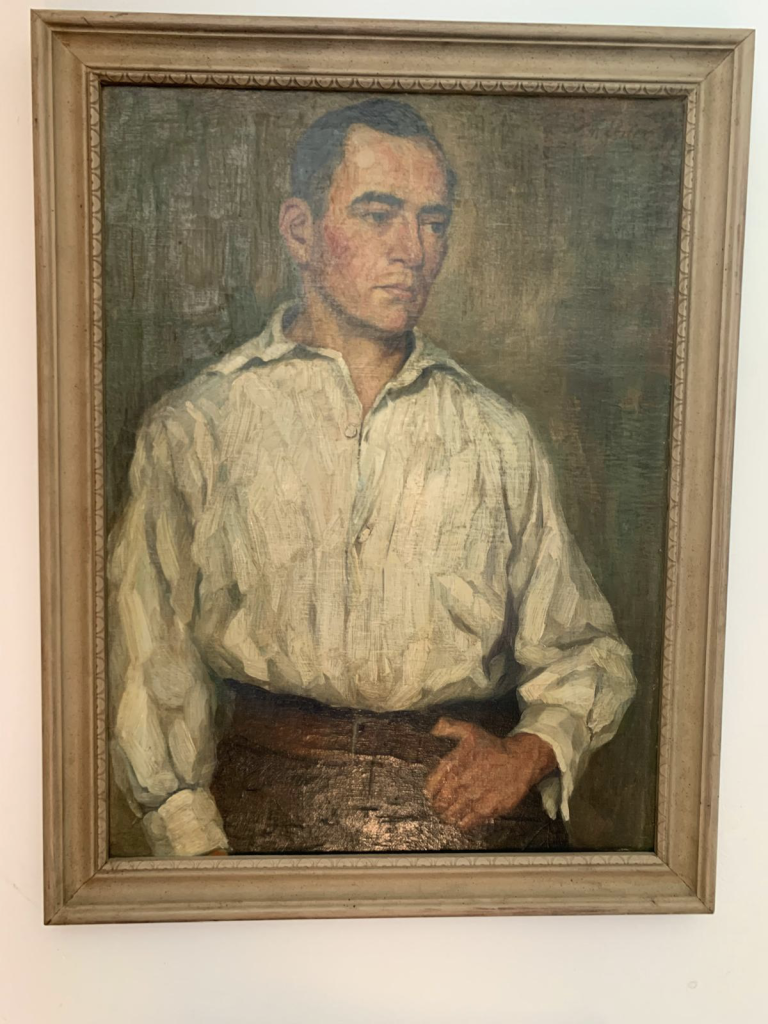

Fig. 1.

The dining room at my grandparent’s apartment used to be dominated by a large painting of a man I never met, a footnote to the lives of my grandparents: “uncle Max.” He and his wife Hilde owned an ironware store with about six employees next to their spacious bourgeois home including six rooms and a small collection of art works. When the Nazis took power, state institutions were banned from doing business with Jewish owned enterprises, which meant significant losses for the Schlossbergers (that was their last name), who up to that point had been a primary partner of the local prison and other state institutions. By 1937, steadily deteriorating income and constant antisemitic discrimination forced them to sell their business below value and leave Germany. Hoping that National Socialism would eventually disappear by itself, they moved their household just over the border to Luxembourg. Yet on May 10th 1940, the German Blitzkrieg overran their new home. They immediately packed up and left. One day later, on May 11th 1940, Max Schlossberger was shot by a low-flying airplane, Hilde Schlossberger survived but ended up in the Gurs concentration camp, which was by then run by the Nazi collaborators of the French Vichy Regime. Through negotiation and petitioning, she was finally able to leave Europe through Lisbon to New York City, where she worked as a seamstress, crafting covers for wealthy people’s furniture so they wouldn’t catch dust during long summer holidays until 1960, when she returned to the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) to spend her remaining years at an elderly care home in Frankfurt Main.

At the tail end of the first election period of the young Federal Republic,1 and under heavy pressure by the Western allies, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims against Germany or “Claims Conference” (an umbrella group covering a cluster of separate Jewish organizations), and the then recently founded state of Israel, restitution efforts took a first legal form under federal law in August 1953.2 In September 1953, Hilde Schlossberger filed for restitution on reasons of loss of property, damage to her career, and the murder of her husband, Max Schlossberger. In June 1954, the regional court in Karlsruhe rejected the latter claim, summarizing its reasoning as follows:

Ultimately, the adequate causal connection between death and persecution is not given. A causal connection is adequate if the measure of persecution was generally suited to make the damaging effect occur. […] The fortune of the claimant’s husband is an unfortunate individual case.

(Entschädigungskammer II, Landgericht Karlsruhe, 0 (EII) 9/54; if not stated otherwise, translations of legal documents are mine)

The court based its decision on three arguments:

- The invasion of Luxembourg, allegedly, was a military action and not an act of racist persecution. Generally, there were many refugees trying to escape the German military at this point – Jewish and non-Jewish people alike. The dangers of the journey, however, were the same for everyone. Therefore, Max Schlossberger’s death was not related to his Jewish identity in particular.

- Although Max and Hilde Schlossberger were persecuted for antisemitic reasons, that persecution was over in 1937 when they resettled in Luxembourg, says the court. The death of Max Schlossberger three years later cannot be causally connected to the earlier persecution. It relied entirely on military causes (see a) instead.

- Lastly, the court argued that even if the shooter had wanted to kill Max Schlossberger in particular, he could not have killed him because he was Jewish, but only because he was on the run. In the eyes of the court, the shooter’s position on an airplane and Schlossberger’s position in a bulk of refugees made it impossible for the shooter to determine Schlossberger to be Jewish. Therefore, he was not killed as a result of racist persecution in particular.

Such was the verdict of the (allegedly) denazified court in Karlsruhe in 1954. Hilde Schlossberger, however, appealed and the case went to the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof, abbreviated: BGH), the highest civil court in Germany. In 1956, Hilde’s lawyer, Dr. Kurt Werthauer responded to the decision of the lower court in written communication directed to the BGH as follows:

The measures of persecution against the Jews undertaken in the Third Reich are an occurrence that had hitherto been unknown to history. Ordinary legal concepts, which aim only at events that take place within legal life (Rechtsleben) in the ordinary way, must not be applied to these measures, which systematize inhumanity (Unmenschlichkeit). In this way, the measures of persecution in the third Reichwhich are situated outside the law blew up the legal system (haben … das Rechtssystem gesprengt). That is why the legal foundations of adequate causality […] cannot be applied in this case.

(Revisionsbegründung in Sachen Schlossberger, Landesgericht Baden-Württemberg, IV ZR 325/55.)

The demand for an adequate causal connection between persecution and death, Werthauer argues, relies on the assumption that some kind of ordinary legality had been in place and that therefore a direct connection between cause (or intention) and effect could be assumed. But given that the legal framework of National Socialism in some fundamental way “blew up” that ordinary legal framework, Werthauer argues, this connection cannot be assumed. In other words: The Nazis did not act wrongly within a correct legal framework, nor did they just make bad laws. Rather, Werthauer argues, Nazi legislation was actually an anti-law, Unrecht – a law against the law. And that is why, he continues, the jurisdiction of the Federal Republic of Germany should not insist on ordinary legal categories.

Taking off from the case of Max and Hilde Schlossberger, this text argues that the insistence on so called “adequate causation” in post-Nazi Germany systematically allowed lawyers to legitimize crimes committed during the Nazi era. Moreover, this insistence on “adequate causation” opposes indeterminacy, thereby echoing Nazi ideology’s identification of abstraction and indeterminacy with Jews (and trans women). Yet again, enmity to indeterminacy is not an accident. It is rooted in the metaphysical structure of value itself. Consequentially, my text calls for a new metaphysics of the law that integrates indeterminacy rather than eradicating it. In other words: Denazification turns on an embrace of indeterminacy.

II. The Dual State

What exactly was that fundamental dis-analogy between law as we know it and Nazi legislation that Werthauer insists on? The first law on restitution was crafted in the American zone of occupation and came into effect already in 1949. It formed the basis for the 1953 Supplementary Law for the Compensation of the Victims of National Socialist Persecution,3 the first restitution law in the Federal Republic which all following amendments were based on. Now, a foundational text within the US American understanding of the Nazi regime was Ernst Fraenkel’s The Dual State, first published in 1940.4 Hilde Schlossberger’s attorney Kurt Werthauer was the only Jewish attorney practising at the Federal Court (BGH) at the time.5 It is thus not unlikely that Werthauer would have had read Fraenkel’s text.

II.a) Normative and Prerogative State

In any case, the distinction between an ordinary way of legal procedure and another order in friction with that ordinary procedure is central to Fraenkel’s analysis. Fraenkel holds that the Nazi state actually consisted of two states. On the one hand, the normative state, based on remnants of the civil code and the Weimar constitution, worked in a decentralized fashion so as to ensure the regular procedures of everyday life. It applied primarily to the economical sphere, because the complexity of individual human interactions could not be directed top down (by decree or prerogative). Or, in the words of Fraenkel, remnants of the normative state were necessary due to “the necessity for decentralization of certain functions in any large scale society with advanced technology.” (Fraenkel The Dual State, 185). On the other hand, the prerogative state centralized political power so as to ensure the general unification of all processes of political life – it brought the state in line with National Socialist ideology and the will of its functionaries. In the prerogative state, party officials who traced their appointment and thus their power back to the ultimate power of Hitler participated in that power by way of sheer command. (Fraenkel The Dual State, 3.) The orders (or commands) given under the auspices of the prerogative state could well contradict the rules of the normative state (and each other). In case of an appeal to a court (which is part of the normative state), judges would mostly show themselves complicit with the prerogative measures.

One of Fraenkel’s many illustrations is the following: The Deutscher Freidenker Verband (German Freethinkers Union) had been forcibly coordinated (Gleichschaltung).6 In 1936, some former employees were claiming compensation for their dismissal from a cremation business that had been connected to the otherwise political organization on the basis of a wage agreement from 1932. “The Reich labor court reduced the essence of the matter to the question of whether an association, despite a change in name, purpose, and legal form (Rechtsform), retained its legal personhood (Rechtspersönlichkeit).” (Fraenkel The Dual State, 244.) If this was the case, then the cremation business had to reimburse the employees for the dismissal. If not, then the cremation business was a different enterprise than the business that had dismissed the employees in question and could not therefore be ordered to reimburse them. What we see here is a clear confrontation between the Gestapo on the one hand – who had dissolved the business by decree functioning as prerogative state – and, on the other hand, the court asked to determine the legality of that dissolution functioning as normative state.7 Eventually, the court rules against the priority of the prerogative measure. Yet the Gestapo develops a workaround: they simply cease the compensation granted by the court. Note that after coordination [Gleichschaltung], all capital of any particular organization was effectively owned by the state. Effectively, the Gestapo took the money from the reimbursed employees and transferred it to the Gestapo. In other words: The state put back the compensation awarded by the court where it had been compensated from, effectively voiding the legal verdict by political decree.

This example shows why Werthauer thinks that the Nazi regime is incompatible with “legal life (Rechtsleben) [as it occurs] in the ordinary way [meaning: the ways of the normative state]”. (Fraenkel The Dual State, 244) The Nazi melange of prerogative measures and normative legal code is bent towards the prerogative state. Particular orders made for particular purposes (such as ceasing some employees compensation) replace the reliability of laws made to apply to all people at all times in a generalized fashion. The prerogative state ultimately undermines the ‘ordinary’ legality of the bourgeois state. The allegedly ‘normal’ parts of stately conduct are nothing but a cover for a regime that ultimately opposes the legal certainty granted by general laws altogether in favor of commands, prerogatives and orders tailor made for particular intentions in particular moments.8

II.b) The Industrialization of the Law

The issue, however, runs deeper. I will now argue that the Nazis industrialized the law in response to the economic challenges of the early 20th century. The confrontation between the prerogative state and the normative state actively causes the production of more prerogative measures, more laws and more legal action in general, such as when claimants appeal against prerogative measures at normative institutions (courts), or when laws have to be crafted to bring the two orders in line, or when some prerogative measure trumps another one. In this sense, Fraenkel says: “When we speak of the state therefore we are using the term in its broader sense, i.e., as the entire bureaucratic and public machine […],” (Fraenkel The Dual State, xxv (my emphasis).)including the party and the ordinary state institutions, but first and foremost both the prerogative and the normative state. The image that Fraenkel suggests is not a mere metaphor: The Nazi state was a machine indeed. Marx, for example, explains the mechanization of labour as follows:

In the modern manufacture of envelopes, for example, one worker folded the paper with the folder, another laid on the gum, a third turned over the flap on which the emblem is impressed, a fourth embossed the emblem and so on; and on each occasion the envelope had to change hands. One single envelope machine now performs all these operations at once, and makes more than 3,000 envelopes in an hour.

(Marx 1976, 500. [translation modified], original: MEGA II.10, 339-340.)

A central aspect of mechanization over against manual labour, then, is the contraction of various activities into one. In this case, at least four different operations are condensed into one single process. Yet Marx insists that mere contraction is not enough. It is important to integrate the principle of movement into the machine as well so as to take human force and agency out of the equation and degrade particular workers to elements of the machine, handlers rather than operators.

As soon as a machine executes, without human help, all the movements required to elaborate the raw material, and needs only supplementary assistance from the worker, we have an automatic system of machinery, capable of constant improvement in its details.

(Marx 1976, 503. [translation modified].)9

Such is the case in a factory. Here, a set of machines operates more or less on their own. The machines are handled and maintained by humans but exceed each individual human’s intention and control as much as they exceed the sum total of intentions and controls of all humans involved. The machine is no longer an extension of human action. Rather, the machine itself becomes the main actor, while humans become extensions of the mechanized process, secondary to it, and ultimately replaceable. In this sense, the factory gives rise to a different kind of labour, one where the machine part is primary, the human part is secondary. That is why the factory does not merely optimize manual labour. It really does mechanize or industrialize labour itself.

In a way similar to the industrialization of labor just described, the Nazis industrialized the state. From early on, the Nazis used all means to unify the disjointed elements of the state and its social sphere (cultural, social, political, intellectual, artistic, military etc) into a coordinated whole (Gleichschaltung) that could be used to pursue a single purpose: “[The unity] of people, war and politics is the victory (Triumph) of the idea of the war of extermination (Vernichtungskrieg) – it is waged internally as well as externally.” (Reemtsmaa “Die Idee des Vernichtungskrieges – Clausewitz – Ludendorff – Hitler,” 397.) Yet even before the state became a mere extension of the German war machine (or during the process of becoming that war machine), it produced laws, measures, orders, and decrees, fuelled and fostered exactly by the friction between instant political measures and the ordinary legal order, between prerogative state and normative state. Nazi legislation integrates the motivating factor for the creation of laws and jurisdiction into the legal system itself, turning humans into extensions of the double aspects of the legal process (normative state vs. prerogative state). It is not, as contemporary humanists would have it, a mere regime of injustice (Unrechtsregime), meaning that the whole system was tainted by the lawlessness of its operating officials.10 Rather, the contentious constellation between the two aspects of the Nazi state turns it into a perpetuum mobile, a self-moving apparatus of the production of legal code. “[T]he existing positive law was developed further on a day-to-day basis through a million individual decisions in the administration and the judicial system.”(Stolleis The Law under the Swastika, 8.) Law is being industrialized.11 The Nazi state does not merely optimize legal operations in service of an evil purpose. Rather, the Nazi state really does mechanize or industrialize the law itself. The state becomes an edifice geared to generate new measures, new code, and new legal material that can then itself function as fuel for the production of more measures, etc. Confronted with the industrialization of economy and society, the Nazis took initiative and industrialized politics as a whole.12 They did not restrict themselves, however, to the extensive usage of then contemporary machinery and media (the radio, the autobahn, synthetic drugs, tanks etc.), mass movements, and the unification of civil society, industrial production, and military in a total war.13 They industrialized the legal apparatus as well. That is the origin of the often cited “banality of evil”: (Arendt Eichmann In Jerusalem) In the factory, the machine itself becomes the main actor, while humans become extensions of the mechanized process. The factory gives rise to a different kind of labour, where the machine part is primary, the human part is secondary. Likewise, the Nazi state poses as the main actor. It denigrates citizens into extensions of a mechanized process. This state gives rise to a different kind of politics, where the party-state is primary, the individual person is secondary (if existing at all). This constellation pays off for the complicit member of the mechanized state: It ultimately allows to relegate responsibility away from oneself and onto a fictionalized agent (the state, the party, the leader, the people etc). That is how the industrialization of the law, the industrialization of the state enables violence and cruelty: it systematically undermines responsibility in favor of submission, identification with a capricious power and participation in despotic violence. Denazification, then, cannot just sort out some bad apples and keep the system running (although, as I will discuss later, not even that happened). It must re-think the problem of industrialization. Yet where that does not happen, injustice prevails – or so I shall argue.

III. Indeterminacy, Abstraction, and Antisemitism

There is certainly no such thing as the “incarnation of some homogenous ‘Nazi ideology,’ let alone the even more chimerical ‘Nazi personality.’” (Griffin Modernism and Fascism, 255.) “[T]he roots of Nazi thought were far too eclectic to be subsumed under the label of biological racism [or any other unifying label].”(Roseman “Racial Discourse, Nazi Violence, and the Limits of the Racial State Model”, 32, see also ibid. 52.) Yet an analysis of some basic traits can still be useful for a progressive understanding of denazification. In this vein, we should notice that the Nazi project was industrial in its execution, but it was metaphysical in nature. The previous section has argued the former point (industrialization). This section will argue the latter (concerning metaphysics). I agree with Moishe Postone and Enzo Traverso that an integral dimension of the Nazi project was the eradication of abstraction as such, phantasmatically projected onto “the Jews,” and identified with the ills of capitalism such as alienation, poverty, isolation. (Postone “Anti-Semitism and National Socialism: Notes on the German Reaction to ‘Holocaust,’” 129.) Yet in order to demonstrate the full complexity of that project and why it cannot possibly succeed, this chapter will proceed in two steps. First, I will provide a deconstructive analysis of the concept of value with a double upshot: We will simultaneously understand where the enmity against abstraction and indeterminacy originates and how it misapprehends the concept of value itself. Secondly, I will combine this analysis with the identification of ‘Jews’ with ‘abstraction’ in European modernity, in general, and in Nazi ideology, in particular.14 This should give us a broad picture of the metaphysical problem embodied in Nazi ideology. Simultaneously, it will show that the jurisdiction on the death of Max Schlossberger was indeed a structural continuation of the project of Nazi ideology: the eradication of abstraction and indeterminacy, phantasmatically embodied in whatever Nazis understood under the term “the Jews.”

A note on terminology: I prefer ‘indeterminacy’ to ‘abstraction’ in this context. The latter comes from the Latin abstrahere: “to drag away, detach, pull away, divert”. It thus suggests a relation between a source and a derivative, some stock of things and something taken away from it. But, as I hope the following analysis will show, ‘taking something away’ really isn’t the problem. A constitutive blur, unclarity or indeterminacy is.

III. a) A Deconstruction of Value

I am now going to develop a deconstructionist theory of value,15 turning on the claim that exchange value lives in the heart of utility itself. To begin with, value can be understood as an infinitive. We call an infinitive the form of a verb which can be universally applied. In that sense, ‘to run,’ is the infinitive because the specific subject/object relations are not yet determined. Dogs and machines may run, may have run, may soon run etc. There are infinitely many applications. That is why it is called “infinitive.” In such a way, we could understand value as an infinitive as well, which is just to say: Everything can be valued or not valued. But how do we determine a particular value? What is the measure of value to be? Who or what is assigning value? There are two classical theories: (Spivak “Scattered Speculations on the Question of Value,” 73.) The materialistic conception of value on the one hand, and the idealistic, liberal conception of value on the other hand.16 The liberal conception of value has it that an individual consciousness paradigmatically assigns value. “I like ice cream.” “I want to be an influencer.” The materialistic conception of value has it that valuation or evaluation is not grounded in an individual consciousness, but in some kind of labor force – in a real, material process that generates the value, such as the time invested or the resources spent during production (Marx Das Kapital, 74).

Both pictures, however, start their analysis with consumption, understood as the act in which the object of consumption is used up in part or completely (or excessively, see Bataille The Accursed Share, 24). Thus, in consuming peanuts, I literally eat them up, in consuming someone’s time, that time is spent in this or that way, in consuming someone’s labour, that person is getting tired and must thereafter recover, in a toxic relationship, desire, pain and the dynamics ensuing from them become destructive and all-consuming, sometimes lethal.17 Yet for the most part, things are not actually consumed. Rather, they are intelligible to us as consumable. A thing’s consumability effectively is its utility – its usability in a certain respect, its intelligibility as having this or that effect if used. There is no consumption without utility (however phantasmatic or unreal it may be). And insofar as utility is nothing but use value, there is no consumption, no enjoyment, no use without use value. In a way, what is consumed in consumability is a thing’s ability to be consumed – it’s a second order consumption or use.

Yet a certain indeterminacy resides in between utility and consumption. For nothing guarantees that the projected effect will actually come to pass. Nothing guarantees that the tasty looking peanut will actually be tasty. Likewise (side eyeing my Marxist friends) nothing guarantees that the labour or the time I put into this text or spend with factory work or any other productive activity will actually make a text, a good text, or whatever other product may have been envisioned etc. Nevertheless, there is no way to prevent a thing from having utility either. For utility is nothing but the intelligibility of consumption, the projected effect that a certain use might have etc. And, as long as there is perception, there will be utility.

The continuously re-occurring mismatch between projection and actualization, between expectation and effect is hard wired into reality as the intimate difference between a thing as it is “in itself” and a thing as it is “for something else” (its intelligibility in a certain respect). I call this mismatch ‘indeterminacy’ (Bataille may call it an “inevitable loss”, though in a less conceptual way, see Bataille The Accursed Share, 31). Such indeterminacy is inevitable. Yet it must be ignored or at least suspended in dealing with particular things. If I light a candle, I expect it to shine some light. Of course, for whatever reason, it may not. But this “not” must be suspended in order for me to light the candle in the first place – for if I did suspect the opposite to happen, or nothing at all, I would not light the candle in the first place.18

Now, nothing prevents use value, utility, the intelligibility of consumption from being applied to itself. For quite obviously, use value itself has a use value – some plot of land may be more useful in the spring than in the fall, or it may be more useful to someone willing to work the land than to a city girl like me. Accordingly, use values can be measured against each other. In fact, that is exactly what happens whenever something is determined to be more or less useful. Here, some use value is itself being used, namely to determine its proper value in relation to other use values. Use value, then, may itself be made use of. Utility itself, in other words, has its own kind of utility. And that second order utility is – mutatis mutandis – exchange value. For what we call “exchange value” is exactly the measuring of different use values against each other (and against an open list of other factors).19 Nothing, then, can prevent use value from becoming exchange value. The utility of some thing, its intelligibility as useful in this or that regard, can itself be used, can itself be measured against other utilities or against utilities for different people. Exchange value, then, lives at the heart of use value, at the heart of each thing, really, insofar as it is perceived by someone as useful in the first place.

I am well aware that this is not a standard idea of the relationship between use value and exchange value. Most theories of exchange value map it onto some other variable, such as labor time (Marx Das Kapital, 74). But why introduce an additional variable (be it time, intention or anything else) if we can explain reality by self-application of the variable at hand (use value)? Let’s keep it simple. As I demonstrate here, you can generate exchange value from use value, or rather: from the application of use value onto itself. This, I take it, distinguishes my model from other models – and I prefer it exactly for its simplicity.

Yet use value by virtue of being use value must exceed the play of mutually determining value-signifiers that is exchange value in some sense, if only by aspiration (Spivak 1985, 80.). Otherwise, it just wouldn’t have the fundamental connection to the consumption of the object that constitutes its phantasmatic relation to use. If I consume a thing, I must really consume it – I must actually eat the cookie, work the land, burn the money and thus take it out of the matrix of mutually determining value signifiers. Yet the act of consumption is not a use value. It’s just an extreme limit of use value, although one towards which use value is directed like a vector or an EXIT sign (never mind whether that door actually exists or leads anywhere). That is as much as we can say about it: use value supposedly exceeds the comparative and mutually determining chains of value signifiers also known as exchange value by fiat. There is, then, an intimate difference between use value and exchange value, just as there is an intimate difference between consumption and use value: They are in fact connected like a Möbius strip, two sides of the same thing, both “inside” and “outside,” distinct only by virtue of their relation to an index, a reference point.20 Use value gestures towards an externality of value (consumption), while exchange value circulates in between values (immanence, dissemination).

Use value, from the perspective of the self-application of the value to itself, is merely the stipulated outside of the concept of value itself, it’s the designated EXIT from the field of mutually determining exchange values. Yet again there is no necessary connection to real consumption or actual enjoyment.21 Hence, there is indeterminacy between use value and exchange value as well. This is why I prefer to speak of “indeterminacy” rather than “abstraction”: Really, exchange value does not “abstract” from use value and neither does use value “abstract” from consumption or anything natural. Rather, they are all dimensions of one another. Nothing “drags away, detaches, pulls away, diverts”. Rather, consumption, use value and exchange value are flavors of one another. They relate to each other like the haptic, the visual and the olfactory dimensions of physical objects relate to each other. They are heterogenous dimensions, neither distinct like pieces of a puzzle, nor unified like water and H2O.

Note that this indeterminacy is independent of any projected system of valuation or determination of value. It occurs whether we determine value materialistically (like Marx) or idealistically. Thus, indeterminacy does not lay with the mode of determination but only with the relation between consumption, use value and exchange value itself, never mind how that value will ultimately be determined. This indeterminacy is the inevitable tendency of exchange value not to match its use value, the inevitable tendency of use value not totranslate into consumption, the inevitable tendency of a projection not to match its actualization.22

But then what? Things may not add up – but that doesn’t mean they evaporate into thin air or nothingness either. The tendency to mismatch involves them being used, exchanged, consumed or actualized otherwise. It tells of the indefinite ways in which things can play out in spite of expectation, calculation and against the odds. Indeterminacy, in this sense, is the condition of any economy whatsoever. It is being avoided at all costs. Security measures, research, testing, contracts, promises, warranties all turn on the avoidance, exclusion, minimization of or deflection from such indeterminacy. Yet due to its inevitability, such avoidance (exclusion, reduction etc.) nevertheless conditions reality. In a way, then, every economy avoids, suspends, ignores, and deflects from this inevitable tendency to go wrong. Spivak gives a number of helpful examples for the ubiquitous applicability of that same logic:

In the continuist romantic anti-capitalist version, it is precisely the place of use-value (and simple exchange or barter based on use-value) that seems to offer the most secure anchor of social “value” in a vague way, even as academic economics reduces use-value to mere physical co-efficients. This place can happily accommodate […] [computers] (of which more later) as well as independent commodity production (hand-sewn leather sandals), our students’ complaint that they read literature for pleasure not interpretation, as well as most of our “creative” colleagues’ amused contempt for criticism beyond the review, and mainstream critics’ hostility to “theory.”

(Spivak “Scattered Speculations on the Question of Value,” 79.)

In all of these cases – use value vs. exchange value, hand-sewn leather sandals vs. mass produced flip flops, reading for pleasure vs. interpretative reading, the magical aura of the object vs. art criticism as a genre in its own right, practice vs. theory – the concrete is staged as the primary, originary position over against a devalued derivative. The latter functions as the vessel for the unruly indeterminacy just demonstrated to reside within consumption and use value already. The devaluation of the derivative (or ‘abstract’) is just a coping mechanism in the face of the constitutive indeterminacy of value. It inversely constructs the reliable enjoyability of the allegedly concrete by way of phantasmatically confining indeterminacy in the secondary, the derivative, the ‘abstract’ – in theory, interpretation, flip flops, etc. Yet, as we have seen in the case of use value, the devalued twin lives at the heart of its romanticized sibling (in fact, this logic is romanticism).23 In the same way, the flip flop lives at the heart of the leather sandal, interpretation lives at the heart of pleasure, theory lives at the heart of practice etc.

This catastrophic indeterminacy, however, cannot be exorcized by way of flipping the table either. Pretending that value was a mere relation between signifiers, exchange values will not do the trick. Spivak calls this fantasy of pure immanence or relationality ‘textualization’: “In my reading, […] even textualization [insisting on the primacy of exchange value, flip flops, interpretation and theory] […] may be no more than a way of holding randomness [inevitable indeterminacy] at bay.” (Spivak “Scattered Speculations on the Question of Value,” 79.) That is to say: Even a wholesale inversion of the romantic primacy of the concrete, determinate, actual over indeterminacy would not yield a better system altogether. In such a textual theory of value, total determination is assured by way of the uninterrupted connection of mutually determining elements. Examples can be signifiers, or relations such as position/negation or causal interaction etc (for an economic model of this kind, see exemplarily Klossowski Living currency, 60-65.) Yet, the unyielding indeterminacy persists. Things may always go wrong – or other than expected. In the context of a theory of value as a sphere of immanence, such indeterminacy allows for incessant re-perspectivation, re-description, re-interpretation, re-naturalization.24 Things are intelligible in infinitely many ways. Nothing can guarantee that this particular exchange value in this particular context really originates in this or that complete chain of determining factors. Instead of falling for Skylla (the romanticism of the concrete) or Charybdis (the romanticism of textuality), we should live inside the problem of value in that we face the material manifestation of the indeterminacy at play,25 rather than ignoring it by looking the other way (to the concrete) or by universalizing it (into textuality). But more on this later.

In the following section, I demonstrate how Nazi ideology is a particularly strong denigration of indeterminacy – and how the case of Max Schlossberger actually continues that same ideology into the jurisdiction on restitution of the Federal Republic of Germany.

III. b) The Metaphysics of National Socialism

The Nazi project is industrial in its execution, but it is metaphysical in nature. In the European 19th and early 20th century, the signifiers ‘Jews’ and ‘Jewish’ came to be identified with abstraction across the board. “As the personification of the abstraction that dominated the social relations of the capitalist, urban, and industrial world, the Jew was stripped of his real features and became simply a metaphor for modernity.”(Traverso The Origins of Nazi Violence, 130.) Accordingly, and in a different way from other ideologies based on race, “[i]n modern anti-Semitism [the power attributed to ‘the Jews’] is intangible, abstract and universal.” (Postone “Anti-Semitism and National Socialism: Notes on the German Reaction to ‘Holocaust,’” 106.) To the present day, “[a]ntisemitism frequently manifests as a concern over putative Jewish hyperpower. […] Jewishness is very much a marked identity—and the markers quite frequently center around beliefs about Jewish power, domination, or social control.” (Schraub “White Jews: An Intersectional Approach,” 379–407, here 384.)

Nazi ideology gives this constellation an additional metaphysical twist. It has as its goal the destruction not just of this or that group, but of the abstract altogether. Thus, “one of the fundamental characteristics of Nazism was its destruction of (Jewish) abstract legal forms by a “concrete scheme of thought” (koncretes [sic] Ordnungsdenken), oriented by the notions of soil, race, “living space,” will, and so on.”(Traverso The Origins of Nazi Violence, 142.) We have seen an example for this in the Dual State: The “abstract” system of laws (the normative state) is supplemented with an allegedly “concrete” order of prerogative measures and commands grounded in mythic authority (i.e. Hitler). Running in the same vein of the violent imposition of a “concrete” order so as to eradicate an “abstract,” we find the phantasmatic identification of “Jewishness” with abstract value or capital and its combination with an antisemitically charged revolutionary psudo-anti-capitalism. In short: extinguishing those phantasmatically identified as “the Jews” was meant to eradicate the undesirable effects of capitalism, especially alienation, atomization, and the power of finance.26

As we have seen, the devalued twin of each allegedly concrete concept (use value, leather sandals, pleasure etc.) lives at the heart of its romanticized sibling. In each case, the conjoined twins can only appear to be separate by virtue of an act of epistemological violence. And this leads us to the metaphysical dimension of National Socialism. The project of National Socialism is metaphysical in that it aims to eradicate the abstract. It is like abolishing colours or countability altogether. It is not the mere redistribution of power or the submission of a particular kind of people. Rather, it is the attempt to fundamentally alter reality itself and not just some of its instantiations. Following our deconstructive analysis of value, it is clear where this project comes from: in order to avoid the constitutive nature of indeterminacy, the concrete is traditionally reified over against its allegedly accidental abstract aberration.

The term “abstract” itself is a symptom of this tendency: Founded on the Latin ab-strahere (to draw away from),it seems to point towards a concrete source as the object of something to be dragged or pulled away from, something detached, diverted etc. In its relationality, the term and idea of ‘abstraction’ seem to relegate indeterminacy (as discussed above) to a place without abstraction, a place where something is taken from, dragged out of, pulled from etc. – an allegedly primordial, independent, concrete, actual source. Thus, in the relation abstract-concrete, the denigration of indeterminacy is already manifest. For really, concreteness must lend itself to be carried, dragged or pulled in order for the ‘abstraction’ to happen in the first place. In this way, there is ‘abstractability’ right there within concreteness. This capacity to lose its concreteness is exactly the indeterminacy of concreteness itself, which is often banished into an allegedly separated term called ‘abstraction’. The originality of ‘abstractness’ also articulates itself in the term often thought opposite to ‘abstract’: For the ‘concrete’ is literally grown (con-) together (crescere). Now, such growing can only occur of parts previously separated – abstracted – from one another. And, linguistically speaking, the term ‘concrete’ must be abstracted from this etymology (“grown together”) in order to mean that which is naturally other than abstraction, other than the dispersed, disseminated, spread out etc. Thus, the ‘concrete’ turns out to be an abstraction of its own meaning – the abstract turns out to be primary after all.

This pattern – deny the constitutive dimension of indeterminacy, reify the concrete, confine indeterminacy in the abstract, then denigrate it– is what Derrida calls the metaphysics of presence, where “presence” in his terminology takes the place of the concrete, of leather sandals, pleasure, use value and consumption. (Derrida Of Grammatology, 49.) The metaphysical dimension of national socialism is thus an especially radical manifestation of the metaphysics of presence. It is the project to make everything present, make everything concrete by way of literally killing the abstract, ideologically located in the Nazis fantasy of “Jews” qua bearers of abstraction, capital etc.27

IV. Re-Nazification

The metaphysics of presence cannot understand the intractable nature of a certain indeterminacy. Yet that indeterminacy structures reality in its entirety and human reality, in particular. Indeterminacy, for example, makes us move around a sculpture. It is because we cannot see the other side from where we stand that we walk around it – the other side of the sculpture might be (and probably is) not exactly what is expected. (Deleuze Difference and Repetition, 56.) It is not unlike the relation between use value and consumption: In both cases, we are dealing with the incommensurability between intelligibility (use value, one side of a sculpture) and reality (consumption, the other side of the sculpture).28 Yet the metaphysics of presence compulsively insists on the eradication of all indeterminacy. In our case, all three dimensions of the court’s decision to reject Hilde Schlossberger’s attempt to gain restitution for the murder of her husband revolve around indeterminacy:

- The court maintains a rigorous distinction between German military action and German antisemitism. Yet research around the famous Wehrmachtsausstellung in the 1990s clearly pointed out that there was no rigorous distinction between German military aggression and German aggression against civilians (labeled “Jews”, “asocials”, “communists” etc) to begin with.29 But furthermore, from the position of the Schlossbergers, the distinction was really indeterminate. They knew that they had been persecuted by Nazis, they knew that this was a Nazi army, and they knew that it would be followed by antisemitic purges. Thus, although there sure was a distinction between Wehrmacht, SS, Gestapo etc. to them, as there was one in reality (however you want to understand that term), that distinction did not consist of strictly drawn lines, but was mostly nominal. Just as the distinction between use value and exchange value is real but permeable, so was the distinction between Wehrmacht, SS, Gestapo in their function regarding the persecution they conducted. Although they were different institutions, they were effectively part of the same killing machinery.

- The court argues that only the Schlossberger’s actual departure from Germany (which ended in 1937) can count as persecution proper, while the departure from Luxembourg cannot. This effectively ignores a crucial dimension of the actual reason for both departures: the projected, indeterminate persecution, persecution to-come if you will. It is the indeterminacy of whether or not the Gestapo will round up all Jews in Luxembourg within a day’s time that set the Schlossbergers in motion, has them pack up and leave at the break of dawn. Even if there was an actual gun on Max Schlossberger’s head, his reaction would still be a result of his vision of a trigger being pulled, a bullet entering his head, an indeterminacy oriented to be actualized in a certain way.

- The court argues that the shooter could not possibly have been motivated to shoot Max Schlossberger because he was Jewish. The argument thus exploits a certain indeterminacy: the shooter supposedly was not aiming at anything in particular, while only persecution on the grounds of some determined category (such as being labelled ‘communist’, ‘Jewish’ or ‘asocial’) supposedly counts as proper reason for financial restitution. Yet shots were fired at a crowd of refugees escaping Luxembourg. Nazi supporters had no reason to take flight in this context. Thus, the whole bulk of refugees consisted of those fearing Nazi persecution. Even if it was true that the shooter could not ultimately determine whether he was about to murder Jews, communists, Sinti, trans people or others with this or that particular bullet, yet that he would most probably kill people belonging to some of these groups was pretty clear. The indeterminacy in this case was thus an integral element of his murderous intention: He shot into the crowd indiscriminately because he was fine with any victim whatsoever. Thus, although Max Schlossberger was not necessarily shot at because his murderer thought him to be Jewish, he definitely was shot at because he was being persecuted – as part of a group made up of people persecuted indiscriminately (indeterminably).

The court’s insistence on the actual connection between adequate causes in line with the metaphysics of presence is thus not merely unjust. It also insists on a forensic nature of reality – a situation where everything is fully given and accessible to comprehension, where things are clearly demarcated from one another, and causal connections can be clearly determined without any rest of doubt. Instantiating that order, however, was a crucial aspect of the Nazi project: Abolish indeterminacy, eradicate abstraction. In this way, the legal requirement of the Federal Republic of Germany for restitution factually continues the Nazi project with other means: it forces a logic onto reality that is ultimately alien to reality. It effectively penalizes those who suffered under the Nazi regime already, in this case: Hilde Schlossberger. In this sense, in this particular case, German restitution legislation continues the Nazi project with the means of the normative state.

Yet this particular case was in no way, as the court in Karlsruhe pretends, an “unfortunate individual case”. (Entschädigungskammer II, Landgericht Karlsruhe, 0 (EII) 9/54, quoted above.) As of 12.31.2020, the Federal Republic of Germany has paid out a total of 79,000 billion Euros in restitutions to victims of the Nazi regime.30 Most of these payments resulted from administrative confirmation of claims for restitution. Only 10-20 % of the claims ended up in court. (Lehmann-Richter Auf der Suche nach den Grenzen der Wiedergutmachung, 286.) Yet how many claims were rejected and did not end up in court remains unclear. Similarly, it is debatable whether the payments were adequate. Hilde Schlossberger, for example, ended up with a monthly stipend of 700 DM for both the property lost and the damage to her career (there was no restitution for the murder of her husband).

In his extensive study of post war Western German jurisdiction on restitution, Arnold Lehmann-Richter states that “the most important factor in the jurisdiction of the BEG [German restitution law, see above] to the detriment of the persecuted had to do with the distinction between damages due to persecution from damages which, in the eyes of the courts, originated less in the persecution than in the general consequences of war or in the general risk of life [Lebensrisiko].” (Lehmann-Richter Auf der Suche nach den Grenzen der Wiedergutmachung, 65.) He observes that the courts “transferred the concept of ‘adequate causal connection’ from civil law into restitution law.” (Lehmann-Richter Auf der Suche nach den Grenzen der Wiedergutmachung, 66.) This echoes Werthauer’s critique of the Federal Court of Justice [BGH] in 1956. The courts however explicitly rejected an interpretation of causality “in the sense of mechanistic causation as it is found in the natural sciences.”(BGH RzW 1956, 81.) Yet overall, “[i]n published legal decisions […] a critical engagement with the theory of adequate causation did not take place at all.”31 (Lehmann-Richter Auf der Suche nach den Grenzen der Wiedergutmachung, 67, ft. 139.)

Werthauer was thus more correct than his letter might suggest: German courts in general (and not just the regional court in Karlsruhe or the Federal Court of Justice [BGH]) treated restitution as just another legal matter, subsuming it under the civil law, feigning an ‘ordinary’ legal situation and thus ignoring the particular challenges at hand.32

In the public and political debates of the ‘50s and ‘60s, the political reason for a restrictive interpretation of restitution law was financial in nature: full restitution for all victims of the Nazi regime would allegedly have brought the young Federal Republic to its knees financially, which was undesirable to the Western allies due to the blossoming cold war.33 But this is only half the story at best.

In 1949, 14423 of the 49121 civil servants [Beamte]in Bavaria were former members of the NSDAP. Yet since 1945, Bavaria had appointed only 265 civil servants that had been persecuted for political reasons and 92 that had been persecuted for racial reasons. The Federal Ministry of Foreign Affairs [auswärtiges Amt] employed more [former] armoured infantrymen [PGs] in the Federal Republic than under Ribbentrop [the minister of foreign affairs from 1938 – 1945].

(Pross Wiedergutmachung – Der Kleinkrieg gegen die Opfer, 54.)

Of the 22 judges and district attorneys of the special court in Kiel available in 1945, 21 (95 %) were back in office by 1951. […] Two-third of them […] were promoted to higher offices. Schleswig-Holstein, however, was not a special case. The same structures [Personalstrukturen] can be observed in the judiciaries of other federal states.

(Godau-Schüttke “Von der Entnazifizierung zur Renazifizierung der Justiz in Westdeutschland”, 55.)34

Walter Strauß, one of the founders of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU, then the governing party) and state secretary in the federal ministry of Justice 1949 – 1963, whose Jewish parents had died in Theresienstadt and whose legal career had been forcibly terminated in 1933, paradigmatically told the judges of the Federal Court of Justice [BGH] at the 75th anniversary of the Supreme Court of the German Reich [Reichsgericht]: “Just as the Federal Republic of Germany is not a new foundation, but a historical and legal continuation of the Reich, […] we also understand the Federal Court of Justice [BGH] not as a historico-legal continuation of the Supreme Court of the German Reich [Reichsgericht], but as identical to it.”35 And Konrad Adenauer (the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, who had himself been imprisoned by the Nazis in 1944) together with his financial advisor Hermann Josef Abs (one of the architect of the “aryanization” of Jewish property, employed in high offices at Deutsche Bank during and after the war)36 in the early ‘50s were planning to reduce restitution for Israel to the founding of a (1!) hospital. (Pross Wiedergutmachung – Der Kleinkrieg gegen die Opfer, 58.) After some of his advisors and negotiators had stepped down, Adenauer finally changed his mind, partially motivated by the allegedly large influence of “international Jewry” [Weltjudentum] at the US stock market – thus on at least partially antisemitic grounds. (Pross Wiedergutmachung – Der Kleinkrieg gegen die Opfer, 67.) In short: The young Federal Republic was clearly marked by continuity with the Nazi regime especially regarding its administrative and legal apparatus, even beyond the lines of Nazi personnel.37

Picking up on Fraenkel’s Dual State and Postone’s analysis of the connection between antisemitism and the concept of value, I argued above that the Nazi regime industrialized legality (with the two cogs “normative state” and “prerogative state”) in the service of its metaphysical project to eradicate the abstract itself, phantasmatically manifested in “the Jews.” We can now see that this general project remained in place beyond the collapse of the Reich, not only in one case, but in many cases. Besides the obvious continuity in personnel, the project of the eradication of abstraction to the detriment of oppressed groups – Jews, communists, gays, lesbians, trans people, so called “asocials” etc. – never stopped. The Federal Republic of Germany continued the Nazi project, in lower intensity and with other means – it was, in fact, renazified, not denazified. It should thus sadden, but not surprise us to learn that the Federal Court of Justice [BGH] rejected Hilde Schlossberger’s appeal and repeated the jurisdiction of the regional court [Landgericht] Karlsruhe word by word. As there was no higher court to appeal to, the jurisdiction remained in place. Legally speaking, Max Schlossberger’s death did not originate in antisemitic persecution. It was an unfortunate individual case – one of many.

V. Indeterminacy Reconsidered

In this section I argue that the Nazi project is in no way specific to the Nazi regime. I will do so by way of two examples: transmisogyny and anti-black racism.

V.a) Trans Misogyny

Joni Alizah Cohen points out that “[j]ust as the Jew becomes the concrete manifestation of the abstraction of capitalism and the law of value, the trans woman becomes the concrete manifestation of the abstraction and denaturalisation of gender.” (Cohen “The Eradication of “Talmudic Abstractions”: Anti-Semitism, Transmisogyny and the National Socialist Project,” italicized in original.) This is the case in Nazi ideology, one of whose first primary targets were Magnus Hirschfeld (“The most dangerous Jew in Germany”, according to Adolf Hitler) (Mancini Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom, 101.) and his Institute for Sexology [Institut für Sexualwissenschaften], which counted trans people among its staff and clients, offered gender affirming surgeries and cooperated with the police to issue “transvestite passes” (Transvestitenschein) that would exempt owners from anti trans police violence. Cohen demonstrates that “the primary object of Nazi persecution of ‘homosexuals’ was in fact the gender variance implicit in their understanding of homosexuality, most pronounced in people who demonstrably showed feminine traits such as dressing in feminine clothing and taking on feminine names.” (Cohen “The Eradication of “Talmudic Abstractions”: Anti-Semitism, Transmisogyny and the National Socialist Project”) In other words: To the Nazis, the paradigmatic homosexual was a trans woman. And the more trans you were, the pore persecution you had to fear.

Now, in a way, the phantasmatic trans woman is pure exchange value. For the trans woman, in her patriarchal framing, mirrors the cis woman.38 She is but a poorly made copy, composed of an exchange of signifiers (“feminine traits such as dressing in feminine clothing and taking on feminine names”, Cohen 2018). And according to the romanticism of the concrete this means that she is but a shameful aberration of nature (meaning: of original masculinity).39 Transness, from the point of view of the metaphysics of presence, is nothing but an expression of the indeterminacy at play between a body and its intelligibility – just as the indeterminacy at play between use value and exchange value, and between intelligibility and reality in general.40 It is thus no accident that to the Nazis – the historical Nazis and their contemporary counterparts – trans women are the pinnacle of bourgeois abstract distorted life style, a point of constant agitation, of panic, rage and aggression, to the point that some imagine a conspiracy of Jewish trans women behind contemporary tendencies of social liberalization. (Cohen “The Eradication of “Talmudic Abstractions”: Anti-Semitism, Transmisogyny and the National Socialist Project”.)41 Yet, it should be clear from our analysis so far that the indeterminacy of gender and its social malleability do not befall a body from a diabolically motivated outside.42 As has been shown over and over again in response to, critique of, and in dialogue with the work of Judith Butler in particular, trans really lives at the heart of gender itself.43 In a patriarchal society however, trans femininity touches a particularly soft spot. It is treason to the allegedly powerful paradigm of masculinity. I will not return to this point explicitly, but it should be clear that denazification implies trans emancipation in a paradigmatic and non-incidental way.

V.b) Anti-Black Racism

In another register, Denise Ferreira da Silva argues that “the emergence of modern science can be described [as] […] an inquiry into the efficient causes of changes in the things of nature.“ (da Silva “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞: On Matter Beyond the Equation of Value”.)44 As the European idea of knowledge closes in on effectivity as determination, the unruly indeterminacy that has haunted us throughout this text must become anathema. (da Silva “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞”.) This framework “is presupposed in accounts of the juridical and ethical field of statements (such as the human-rights framework)” in two ways: (da Silva “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞”.)

- Some universal framework (a legal code, human rights, universal ethics) is said to apply everywhere without constitutive indeterminacy between the framework and the cases subsumed.

- The objects of these frameworks must fit neatly into the categories in place and must be conceivable by a rational human mind (such as the mind of the judge in place).

Yet blackness, da Silva continues, has generally been labelled and treated as the indeterminate matter of (white) action and cultural development. Riley Snorton provides a prime example for this process: the role of black slaves in the development of gynaecology. James Marion Sims developed his medical techniques and instruments while conducting experimental surgeries on enslaved black women without anaesthesia. His name is part of medical history until the present day, his enslaved collaborators – Lucy, Betsey, Anarcha and many more – remain all but nameless to the point that at times it is unclear in his own notes whether he knew their names at all. (Snorton Black on Both Sides – A Racial History of Trans Identity, 23.) Sims’ “procedures of ‘total objectification’ […] [aimed at producing] subjectified objects of flesh.” (Snorton Black on Both Sides, 34.) This notion of the body as malleable flesh has since become paradigmatic not only in gynaecological surgery. It is also, for example, the medical departure point for gender affirming surgeries for trans people – surgeries that thus hinge on a material history of racism and exploitation.45 The case, however, is paradigmatic for the phenomenon described by da Silva: black bodies function as indeterminate matter to the determining effective causes enacted by hegemonically identified (often white) subjects. In this sense, “racial knowledge transform[s] the consequences of hundreds [of] years of colonial expropriation into the effects of efficient causes (the laws of nature) as they operate through human forms (bodies and societies).” (da Silva “1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ − ∞ or ∞ / ∞”.) Blackness is rendered indeterminate, utterly material, and then erased from history, memory, and perception.

Indeterminacy is being denigrated, ostracized, and harmed, if not murdered, in its phantasmatically manifest form. Yet in the case of anti-black racism, enmity is directed not against the abstract indeterminacy of exchange value, but against the concrete indeterminacy of matter. That is to say: Anti black racism is not the same as antisemitism.46 And yet, they share a common source: incapacity to deal with indeterminacy and the phantasmatic manifestation thereof in a particular group of people.47

VI. Staging the Law – Denazifications to Come

Enmity towards indeterminacy is not specific to National Socialism. What makes the Nazi project particular is the radicality of this enmity – to not only subject, exploit, enslave the designated location of indeterminacy, but to aim at eradicating indeterminacy itself and altogether. Nazi ideology in this sense is not merely a wicked political project. It is also a metaphysical assault against reality itself. Although it was doomed to fail on that level, it nevertheless did wreak havoc along the way. Despite the differences between Nazi ideology and other modes of oppression (some of which I commented on in the previous section), it is exactly the anti-real radicality of this project that allows us to see a general pattern maybe more clearly than we could see it elsewhere: reification and denigration of indeterminacy, violence against (or murder of) its phantasmatic manifestations.

It has already become clear that the denazification of West Germany in the ‘50s and ‘60s was mostly a failure.48 The attempt to cut off the heads of the hydra and hope that the former Nazis will somehow adjust to the new regime had dire consequences that have been widely documented and discussed. Their repercussions still play an important role in the politics and the psychic life in and beyond Germany.49 However, for the remainder of this text, I want to ask: What could a denazification of the law look like?

As should be clear by now, denazification must entail a new understanding of legality as such. The dismissal of Nazis from office, the reformation of Nazi legislation, the demolition of the prerogative state, the memorialization of past violence, payment of restitutions and reparations are surely necessary conditions, but besides not being properly enacted, these measures effectively missed the crucial point: Nazi ideology was a response to the metaphysical problem of inevitable indeterminacy with then contemporary technological means, namely industrialization. Rolling back the means and apologizing for a bad solution is not going to do the trick. Once the paradigm of pre-industrial denigration of indeterminacy has been shattered, there is no going back.50 What is required is another legal approach to this metaphysical problem.

For now, I can only gesture towards such an approach. My suggestion, however, is this: The law is commonly understood as some sort of commanding signifier that ought to be obeyed like a religious order. And where it is not obeyed, where indeterminacy raises its recalcitrant heads, the police, the military, or another authority is thought to use violence to bring the malefactor in line and restore the sacred and determined order. Yet that is not how the law actually works. For most people simply do not know the law, or they interpret it very differently, and most of these interpretations are never scrutinized with legal precision. Where they are, interpretation has its place yet again. The existence of courts of appeal and the right to remain silent attest to this. In them, the re-occurrence of misinterpretation is institutionalized. Courts of appeal indicate that legal decisions may be wrong, that the law can be misinterpreted and thus require re-interpretation. This counts for courts of last resort as well, even though legally, they should terminate this problem. The case of Max and Hilde Schlossberger exemplifies this.51 The problem of indeterminacy is institutionalized in the right to appeal. Similarly, the right to remain silent manifests that a defendant may mis-speak, that interpretation may distort a statement and that an institution might commit violence in the name of the law. In a way, the existence of attorneys responds to the same problem: in order for the law (personified by a judge) to be able to interpret a case, it must first be translated into legal code. And in order to do that, someone must speak of the case in the language of the law. We call that person an attorney.

In this way, indeterminacy is already integrated into legal practices. It is just (or justly?) disavowed. Yet we may wonder: What would a legal practice look like that integrates indeterminacy even more positively and turns it into a column of the state? I want to suggest that the law is always and anyway already staged, as in a theatre production. Legal code is like the direction of a theatre production. And although this performativity of the law is everywhere denied, it is nevertheless everywhere in place. In fact, the law works best if it is not enforced by any legal or executive authority. Yet such non-enforcement does not mean that everybody follows the rules. What it means is that most people improvise around it in such a way that it does not create enough friction to actually call in the cops. My suggestion is that this should not just be an accidental effect, not just the inevitable expression of indeterminacy. It should be the way the law is being written – with an eye on improvisation and future determination. Call it performative justice, envisioned as a participatory social process, a collective improvisation based on, but not determined by the legal script.In the same way, judges should take the law not as determining commands, but as directions to be adjusted to the situation at hand. Of course, such a proposal can only work out to the benefit of a community if that community is integrated in the development of the constantly evolving considerations under which the legal proposals at hand are to be enacted, put in place, and performed. That is why denazifications (in the plural) must always remain to come: given that the metaphysical problem with indeterminacy is a real problem, it will not go away. Yet we can say about denazification what Spivak says about critique: brushing your teeth is a critique of mortality. It must happen continuously and some day you might lose the battle. (Spivak “The Trajectory of the Subaltern in My Work,” 53:00 min.) The same counts for denazifications as integration of indeterminacy, especially regarding the indeterminacy of the law: the community of those improvising based on the law must be thought of as constantly changing and the relevant context of cultural input onto legal authorities and their legal practices must be conceived of as malleable in this way as well. What it takes is a legal culture beyond compulsive neuroses, per-emptive submission and quasi-religious subjection to a sacred text. The first steps in this direction, however, must be conceived of as an artistic task. What could a denazifying, improvising, pro-indeterminacy legal practice look like? In The Broken Jar, Heinrich von Kleist depicted the transformation of a jurisdiction based on local custom and legal privileges to the Enlightenment ideal of equality before the law. What it takes now are contemporary artists who can imagine the writing of the legal text itself and its interpretation in court as a creative, collective and in principle interminable project. The court room was developed based on the theatre. (Parush “The Courtroom as Theater and the Theater as Courtroom in Ancient Athens,” 118-137.) We should resuscitate that connection. Yet it must happen with the means of contemporary technology. Can we re-imagine the court as a digital theatre, a collective practice of negotiating and re-negotiating justice? A virtual reality with actual impact?

Notes

- Note that the first laws about government subsidies for widows, orphans, returning soldiers, and victims of the war were put in place as early as 1950. ↩︎

- “The German compensation efforts were codified in three laws of the 1950’s and 1960’s. The first law, entitled the ‘Supplementary Law for the Compensation of the Victims of National Socialist Persecution,’ enacted October 1, 1953, implemented the initial German compensation program. It, in turn, was followed by the ‘Federal Law for the Compensation of the Victims of National Socialist Persecution’ of June 29, 1956, which substantially expanded the first law’s scope in favor of those receiving compensation. The ‘Final Federal Compensation Law,’ enacted on September 14, 1965, increased the number of persons eligible for compensation as well as the assistance offered. The final deadline for application under the BEG was December 31, 1969.” (United States Department of Justice Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, “German Compensation for National Socialist Crimes,” in: Brooks When Sorry Isn’t Enough—The Controversy over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice, 62. ↩︎

- The law was “supplementary” because it transformed the law crafted for the US zone of occupation in such a way as to apply to the Federal Republic of Germany as a whole. ↩︎

- See: von Brünneck 2001. For Fraenkel’s role in post war Germany, see also Buchstein 998, 458-461. Another important influence was Franz Neumann’s Behemoth. See Hayes “Introduction”, in: Franz Neumann, Behemoth – The Structure and Practice of National Socialism 1933 – 1945, Vii. ↩︎

- “Jewish Experts Ask Germany to Improve Indemnification Law”, in: Jewish Telegraphie Agency – Daily News Bulletin, 01/15/1954, <https://www.jta.org/archive/jewish-experts-ask-germany-to-improve-indemnification-law>, also: <https://pdfs.jta.org/1954/1954-01-15_010.pdf>, accessed 03/01/2022. ↩︎

- Gleichschaltung is the German term applied to the institutional Nazification of German society after the Nazis seized power in 1933. All social institutions, including political, cultural, and artistic institutions, were meant to become subject to control by the NSDAP (National Socialist German Worker’s Party). The goal was a One-Party-State, where everything would be coordinated through one central force, the Nazi Party, lead by one central person: Hitler. Although Gleichschaltung was a top-down process, it was often met with welcoming complicity on the side of local institutions. Hitler is reported to have been surprised by the speed and efficiency of the process: “everything is going much faster than we ever dared to hope.” (Thamer erführung und Gewalt: Deutschland 1933– 1945, 233). See also Lidtke The Alternative Culture: Socialist Labor in Imperial Germany. ↩︎

- Gestapo is short for Geheime Staatspolizei – secret state police. The Gestapo was a key player in the persecution and elimination of political resistance by the Nazis in Germany and in occupied territories. ↩︎

- In fact, the illusion of normalcy kept the terrorizing aspect of the Nazi regime afloat. See Stolleis The Law under the Swastika, 160. ↩︎

- One might wonder why the physical set up of the machine does not figure more prominently in this description. In fact, I do believe that restricting the terms ‘mechanization’ and ‘industrialization’ to the development of machines falls prey to a bourgeois ideology of progress and misses the point about what industrialization really is. ↩︎

- This would be the thesis suggested by Franz Neumann, but also Max Horkheimer, Otto Kirchheimer, and others. See Fuchshuber Rackets – Kritische Theorie der Bandenherrschaft. ↩︎

- For some examples, see Neumann Behemoth – The Structure and Practice of National Socialism 1933 – 1945, 522. ↩︎

- See also Griffin Modernism and Fascism – The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler, 253. ↩︎

- For some outstanding case studies, see: Traverso 2003, 77; Birdsall Nazi Soundscapes: Sound, Technology and Urban Space in Germany, 1933–1945; Ohler Der Totale Rausch – Drogen im Dritten Reich. ↩︎

- On the historical causes for German antisemitism in particular, see: Nirenberg 2014; von Braun 2000, 149–213, 156 and Carter Race: A Theological Account, 79. ↩︎

- For other approaches, see especially Spivakwinter 1985, but also Derrida 1991, 34; Derrida 1992, 112 and Schrift 1997. ↩︎

- The most prominent proponent of the materialistic version is certainly Marx, the most prominent proponent of the idealistic version is probably Locke. For the real history of capitalism in its relation to colonialism and the theft of actual land, see exemplarily Bhandar, 2018 and Federici 2004. ↩︎

- In this way, the logic of consumption is also the logic of reproductive labour – in order not to be used up completely, people need to have their resources restored, so as to be consumed again, survive another day at the office, another onslaught of toxic attachment etc. ↩︎

- That is why the increasing usage of computation in the production of goods manifests a fundamental transformation of the concept of property as such. ↩︎

- There is, of course, a second order exchange value, where some thing’s exchange value is in turn used so as to generate more exchange value, such as in cryptocurrencies or stock exchange. ↩︎

- For an analysis of this difference/connection in a materialistic vein, see Derrida Life Death, 37. ↩︎

- Both ‘real consumption’ and ‘actual enjoyment’ in this context function as stipulated limit cases – they don’t actually have to exist in order for my argument to work. ↩︎

- Derrida calls this most fittingly adestination – the non- or anti-aim, -purpose or -destination. See: Derrida La Carte postale: de Socrate at Freud et au-dela, 35. ↩︎

- See de Man The Rhetoric of Romanticism, also Ronell Dictations: On Haunted Writing. ↩︎

- In the spirit of Hasana Sharp’s concept of “renaturalization”: “Examining Spinoza’s framework as a whole, we discover ‘Ideology’ to be a feature of natural rather than exclusively social (human) existence, and the project of critique becomes an engagement with the ‘life force’ of ideas.” (Sharp Spinoza and the Politics of Renaturalization, 63.) ↩︎

- There are, of course, projects that do not directly align with the ideological formation that I describe here: “Unlike European primitivism more broadly, which sought to replace the [abstract] European subject with the [concrete] primitive object, Jewish primitivism was the struggle to be both at once— European and foreign, subject and object, savage and civilized.” (Spinner Jewish Primitivism, 4) ↩︎

- See Postone “Anti-Semitism and National Socialism: Notes on the German Reaction to ‘Holocaust,’” 110. ↩︎

- It should be noted that it wasn’t exactly easy for Nazi legislation to specify who exactly should qualify as ‘Jewish’, see Hilberg The Destruction of the European Jews, 65. ↩︎

- In this way, indeterminacy in the subject is the structural reality of the unconscious, see Spivak “Revolutions that as yet have no model: Derrida’s Limited Inc.,” 33 ↩︎

- See exemplarily: Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung (Hrsg.): Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941 bis 1944 (Katalog zur Ausstellung „Vernichtungskrieg – Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941 bis 1944“), Red.: Hannes Heer und Birgit Otte, Hamburger Edition, 1. Auflage, Hamburg 1996, 30. Also Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung (Hrsg.): Verbrechen der Wehrmacht. Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges 1941–1944. Ausstellungskatalog, Gesamtredaktion: Ulrike Jureit, Redaktion: Christoph Bitterberg, Jutta Mühlenberg, Birgit Otte. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2002. ↩︎

- German Federal Ministry of Finance, “Public sector compensation payments” (Last updated on 31 December 2020), <https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Standardartikel/Themen/Oeffentliche_Finanzen/Vermoegensrecht_und_Entschaedigungen/englisch-leistungen-oeffentlichen-hand-wiedergutmachung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=12> ↩︎

- Such a critical engagement might have lead exactly to the question of media and technology already mobilized above. For it is the technological development of the 19th century that enables an understanding of criminal investigation as a forensic enterprise. A proper denazification of legal practices would have involved a detailed understanding of the industrialization of these indexical practices. 19th century fingerprints, photography, audio recording and other media rely on the direct confrontation (called ‘indexical’) between different materials, such as light and paper (in photography) or skin and surface (in fingerprints). The idea of ‘adequate causation’ is an expression of this development. “The nineteenth century witnessed a rearrangement of the hierarchy of judicial proof, as the value previously accorded to witness testimony was replaced by the scientific reputation of the analysis of indices. […] [T]he sine qua non of a hunt for clues [hence adequate causes], a trial based on evidence as opposed to testimony and confession, dates only from the middle of the eighteenth century. This new concept of evidence transformed both the narrative logic of signs of guilt and the methods of recognition. Instead of reading conventional signs imprinted on the criminal body with the force of sovereign power [through torture], [forensic] detection was approached as a science, employing careful measurement and observation, privileging regimes of knowledge over brute force.” (Charney Cinema and the Invention of Modern Life, 22.) But how was this logic translated into a regime of prerogatives? And how is it transposed into the age of AI and machine learning? ↩︎

- It should be noted that Lehmann-Richter himself favours the application of the principle of adequate causal connection, although he is very critical of its application. His reasoning, however, does not seem sound to me. Without the principle, he argues, relatives of someone who escaped Nazi persecution and then died of a car accident in their new home would be entitled to payments by the government although the accident was mere“fate [Schicksal]”. Lehmann-Richter, Auf der Suche nach den Grenzen der Wiedergutmachung page number? ↩︎

- See Lehmann-Richter Auf der Suche nach den Grenzen der Wiedergutmachung, 283, also Pross Wiedergutmachung – Der Kleinkrieg gegen die Opfer, 118. ↩︎

- For a case study on one of the most influential legal scholars of the Federal Republic of Germany, see Stolleis 1998, 185. For an overview of post-war German discourse on Nazi legislation, see Stolleis The Law under the Swastika, 40. ↩︎

- Bericht der Juristenzeitung (JZ) “Zum 75. Geburtstag des Reichsgerichts“, in: JZ 1954, 680. ↩︎

- For more on the role of Abs and the Deutsche Bank in the so called ‘aryanization’, see James The Deutsche Bank and the Nazi Economic War Against the Jews. ↩︎

- For a more detailed analysis of the complex composition of the fourth civil court of appeal at the Federal Court of Justice [BGH], which is the court that heard the case of Hilde Schlossberger, see Godau-Schüttke “Von der Entnazifizierung zur Renazifizierung der Justiz in Westdeutschland,” 58. See also Lehmann-Richter Auf der Suche nach den Grenzen der Wiedergutmachung , 286 for a general assessment. Also Greve Der justitielle und rechtspolitische Umgang mit den NS- Gewaltverbrechen in den sechziger Jahren, 396. ↩︎

- See Cohen 2018, but also Baudrillard Seduction, 8, 15. ↩︎

- Note that even skilled critical thinkers are not immune to the seduction of transmisogyny, see for example Spivak “Displacement and Discourse of Woman,” 52, 67. ↩︎

- See also Bettcher “Trans Identities and First-Person Authority”. ↩︎

- also Peterson, Montgomerie, Stein 3/6/2021 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jj-VEM6hx_k> ↩︎

- See also deLire “Transsexuality at the Origin of Desire”. ↩︎