Ryan Tracy

Knox College

Volume 16, 2024

We liked the fascists.

Gertrude Stein, Everybody’s Autobiography1

We liked the fascists. Thus spoke Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) on the pages of Everybody’s Autobiography (1937), the follow-up to the bestselling The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933). Can we forgive such a phrase, appearing, as it does, under Gertrude Stein’s signature in 1937, at a time when fascist imperialism had taken hold in Italy, and when the Nazi regime in Germany was consolidating its own brand of antisemitic authoritarian terror? Shouldn’t we think it proper, morally right, for Stein to have resisted fascism at all costs and in all of her statements—to hate fascism with every breath, or, at the very least, not to like it? Can’t we move on from this nonsense? Gertrude Stein liked the fascists. Q. E. D. Cancel Stein.

I open with this admittedly defensive provocation for a few reasons. First, when one can run into a young queen at a party who hasn’t read Gertrude Stein but has read enough about Gertrude Stein to vaguely accuse her of being a fascist—Oh, wasn’t she a fascist or something? said this queen—then it is incumbent on Stein scholars, and queer Stein scholars in particular, to answer to the question of Stein’s politics and to make a stronger case for reading her work. Second, Stein’s frank confession underscores the limits of Modernist Literary Studies’ ability to operate as categorically “anti” or against fascism. To read within the modernist canon is to bring oneself into contact with fascism’s history and the traces of pro- and antifascist sentiment that register the globalized political context in which modernism unfolded.

Thirdly, I wish to broach this essay’s underlying proposition—that there is no one resistance to fascism, and that the history of antifascism includes resistances to antifascism that must be understood in order to know what we mean by “fascism” and how we articulate oppositions to it. If, as the editors of this special issue have argued, fascism should be thought of as “a logic of violence rather than simply a mid-century European historical phenomenon” (Martell and Williams), then it remains our responsibility not only to denounce forms of violence that are easily legible as fascistic, but also those that might be ensconced within antifascist movements, or movements and discourses that operate under antifascism’s banner.

It must be said that “antifascism”–that is, organized and ad hoc resistance to the historical fascisms of the twentieth century and beyond–is rather a latecomer to the train of resistance struggles in the West. And like many upstarts, it did not always acknowledge the work of those who came before it. In the racially segregated United States of the 1930s, for instance, black liberation struggles were scuttled under the rollout of state-sponsored resistance to European fascism, which occurred during what scholars refer to as the nadir of American race relations.2 Contemporaneous calls for Americans in generalto resist fascism overseas led African American critics—who had voiced univocal opposition to fascist Italy’s 1935 invasion of Ethiopia against the grain of an often indifferent American public and mainstream press—into the double position of being both antifascist and, when it came to nationalist calls to fight fascism in Europe, anti-antifascist. Satirist George S. Schuyler, who was a major critic of the Ethiopian invasion and the League of Nations’ failure to prevent Italian aggression against a member nation, articulated this particular resistance to nationally voiced antifascism in the pages of the Pittsburgh Courier: “The simple truth of the matter is that we already have fascism here and have had it for some time, if by fascism one means dictatorial rule in the interest of a privileged class, regimentation, persecution of racial minorities and radicals, etc.” (38). Thus, when antifascism was framed as a resistance to something that was only happening in Europe, African American critics found themselves fighting a dual front against two forms of “fascism,” with one form of fascism—white American nationalism—calling itself “antifascism.”3

Feminism was another resistance discourse that troubled the fault lines of antifascism grounded in national consensus. When the liberal governments of America and Great Britain were calling for their citizens to rally together against the fascist menace overseas and on the continent, feminist critics, such as Gertrude Stein and her modernist contemporary Virginia Woolf, voiced opposition to nationalist antifascist appeals by pointing out that “fascism,” as it was being defined, seemed to reflect the conditions of life for most women under Western patriarchy. In other words, feminists of the 1930s noticed that antifascist national discourses were willfully blind to the fascistic treatment of women within their own borders. In Three Guineas (1938), Virginia Woolf takes a slightly different tack than George Schuyler. Though Woolf clearly viewed patriarchy as a kind of fascism, she cautions against calling the systemic oppression of women “fascism.” For Woolf, doing so would be “merely to repeat the fashionable and hideous jargon of the moment” (137). Woolf’s comment underscores how “fascism” could be viewed as a fad, the latest fashion in state violence among so many others, many of which, like patriarchy, had been around for a very long time. Her vision of a “society of outsiders” and an alternative institution of education that would come to the nation’s aid by resisting the normative demands of the patriarchal state purposefully ran interference on the supposed unanimity of antifascist resistance during the 1930s. There is therefore a precedent among feminist critics for insisting on the necessity of marking feminism’s resistance to state-sponsored antifascism when “fascism” was being defined as the most urgent threat to the state—a threat that, though menacing, lay conveniently beyond the nation’s borders.

In what follows, I will closely read Gertrude Stein’s nuanced and, for the most part, transparent self-positioning between feminist, democratic, and antifascist commitments, while diving into antifascist condemnations of Stein that have emerged over the past few decades. I will also parallel Stein’s work and the antifascist reception of Stein’s work with that of Algerian-born philosopher and literary critic Jacques Derrida (1930-2004)—a writer who, like Stein, has been the subject of controversies around historical fascism. I will show that Stein and Derrida’s resistances to fascism (and to “antifascism”) overlap around the double exclusion of the feminine that can occur within the head-to-head conflict between fascism and the purported enemies of fascism. By doing so, I address this special issue’s motivating question about the usefulness of deconstruction for antifascism’s desire to destroy fascism, and to show that feminism was an important historical point of resistance to antifascism as it was being articulated in national and institutional discourses in the mid-twentieth century.

Before continuing, though, I wish to turn to the motif of the “Auntie,” both as a pun with the “anti” of antifascism and as recurrent figure in Gertrude Stein’s work. I follow, here, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s contention that a critical thinking of “avunculate” or aunt/uncle relations could be “imaginatively exciting and politically important” for scholarly projects (71). In particular, Sedgwick argues that research in the avunculate might help dislodge the stranglehold “Oedipal” models of kinship have over literary analysis, including “deconstructive” readings of sexuality that propose to subvert gendered and sexual binarisms (53-55). Sedgwick laments the tendency of such readings to obscure the plethora of kinship relations that play important and sometimes leading dramatic functions in literary works, such as Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), under the pretense of interrogating the “Name of the Father” or other Oedipally-centered “modern” models of sexual identification and desire. In contrast, Sedgwick beckons us to “Forget the Name of the Father!” by directing our attention to the way certain texts themselves enact a forgetting of fathers (59). For Sedgwick, “the making visible of aunts and uncles” (61) in narratives of family and history turns a spotlight on the “space of nonconformity” (63) that avunculate circuits make possible, as well as the many positions that already obtain in “the actual extant relations” (72) of social life, whether of the family or the nation-state.

Gertrude Stein left literary traces of a father-forgetting, avunculate thinking of “aunts” dispersed throughout her writing, and which can help us think through, I argue, the complexity of political positioning that unfolds when fascism forces a discursive realignment of social relations, including positions that understand themselves as “anti” or against fascism. I thus summon Stein’s frequent thinking of aunts as a resource for addressing modern crises of thought, writing, and politics.4 (For clarity, I grew up pronouncing aunt with the short “a” of “ants,” like Dorothy Gale’s “Auntie Em” from the fascist-era film The Wizard of Oz (1939) (an exemplary auntie who brought aid to Dorothy in her most precarious moment of distress by encouraging her to forget about Oz and its paternalistic Wizard). Though scant scholarship has addressed Stein’s aunt-filled textual imaginary, aunts play an important role in her writing, theories of writing, and autobiographical reflections. In “Portraits and Repetition” (circa 1934), Stein credits two of her most well-known theories of language to her aunts. Her theory of repetition, or, rather, her deconstructive idea that, strictly speaking, “there is no repetition” in spoken language because the living moment in which repetition occurs is always altered by “insistence,” came to Stein after she had moved from Oakland to Baltimore to live with her extended family. This family included “a whole group of very lively aunts” whose constant conversations prompted Stein to reflect on the differences at work in repetitious language (“Portraits and Repetition” 289). Living with her aunts inaugurated a new era in Stein’s life, which she called the “beginning of knowing what there was that made there be no repetition” (290). Stein also credits these aunts with helping her realize “the essence of genius,” that is, the ability to talk and listen at the same time (290).

Birgit Van Puymbroeck has recently remarked that Stein turned to her aunts to develop an “antipatriarchal” and political “antiexpansionist” theory of counting (201). In her introduction to “Let Us Save China,” Stein’s little-known response to the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War, Van Puymbroeck portrays Stein as an advocate of military restraint and economic openness between nations, which Stein associated with a Chinese method of counting. Instead of counting by accumulation (e.g. “1, 2, 3…”), the way Western imperial societies teach, Chinese people count abstractly “by one and one [and one]… as my little aunts did” (Stein in Van Puymbroeck 324). Van Puymbroeck is right to bring Stein’s thinking of Chinese counting in relation to Stein’s belief that Jewish people were part of a salutary diversification of a “finished” Europe—what Stein calls the “peaceful Oriental penetration” of the “Western world” in Everybody’s Autobiography.5Van Puymbroeck also demonstrates that Stein links her thinking of Chinese counting to her commentary on “depressing” fathers in Everybody’s Autobiography, where Stein describes pre-communist era China as “more a land of mothers than… a land of fathers. Mothers may not be cheering but they are not as depressing as fathers” (Stein in Van Puymbroeck 201). Though here, Stein thinks of mothers as a gendered counterweight to depressing fathers, Stein’s linking of aunts with non-accretive (and perhaps non-procreative) counting suggests that aunts might be a better figure for interrupting the forms of political violence that follow from accretive, kingly counting, as well as modes of queenly counting that would simply mirror that of kings. (I will address Stein’s critique of “fathers” later in this essay.)

Yet Stein’s most iconic reference to aunts is likely her beloved first automobile, the Ford ambulance Stein purchased so that she and Alice could be volunteers for “The American Fund for the French Wounded” during World War I. Stein and Toklas named this ambulance “The Auntie” after Stein’s aunt Pauline who “always behaved admirably in emergencies” (Alice B. Toklas 172). Like the aunts who helped Stein think through crises of language and embodied speech, “The Auntie” came to the aid of moral, political, and militaristic crises in France. What I call “Auntie”-fascism, then, can be understood as a way of behaving admirably before the emergency of fascism, that is, before the emergency produced by the emergence of fascism, and the emergence of antifascismas an oppositional force prone to mirroring what it opposes.6 Much like Derrida’s conception of deconstruction as embodying the “problem” of “how to behave in front of texts” (we might say, before the crisis of any text), “Auntie”-fascism outlines the problematic of how to act before, or when faced with, the text of fascism (“Women in the Beehive” 168). In this sense, “Auntie”-fascism does not take sides with fascism against antifascism. Nor does it dogmatically rely on consensus to oppose a non-specific or conveniently selected “fascist” straw man. Rather, “Auntie”-fascism’s avunculate angles re-marks the “space of nonconformity” (to borrow Sedgwick’s phrase) out of which the fascism-antifascism binary is forged and underscores how challenging it can be not to let “antifascism” devolve into a series of accusations and recriminations. In other words, “Auntie”-fascism can come to antifascism’s aid by keeping antifascism open and attuned to important differences within antifascism.

The Stein and Derrida Affair(s)

As I have mentioned, Gertrude Stein and Jacques Derrida have each been subjected to the spirit of antifascist criticism. Along the way, each has been accused of “collaborating” with fascism by masking right-wing sympathies in their writing.7 In the 1980s, Derrida was drawn into—and, admittedly, played his own part in—a series of so-called “affairs.” Less romances, though never without erotic connotations, these “affairs” were intellectual altercations that took place in the media between 1987-88, centering not only on the Nazism and antisemitism of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger and Derrida’s friend Paul de Man, respectively, but also on the question of the relationship scholars should have with these writers and their writings. Common to these “affairs” was the problem of distorted and tendentious “readings” of texts by those most vehemently condemning fascism and Nazism, leaving scholars like Derrida on the defensive and advocating for more patient and scholarly approaches to these problems.

The first “affair” broke with the publication of a condemnatory book: Victor Farías’ Heidegger and Nazism (originally published in French in 1987). The book, claiming to expose hitherto unknown (or ignored) facts about Heidegger’s Nazism, provided leverage for attacks in the media, not only against Heidegger, but against scholars, like Derrida, who drew heavily on Heidegger’s work. Around the same time, a “De Man” affair broke when The New York Times reported on Paul de Man’s wartime antisemitic writings, which had been unearthed by a graduate student who was doing archival research on de Man’s early work. Though de Man’s Nazi-era essays would not be published until the following year, knowledge of de Man’s pro-Nazi work was enough to prompt swift condemnations in the press. Those who had been rankled by the popularity of deconstruction in the Anglo-American university found Derrida’s proximity to Heidegger (as a touchstone for philosophical reflections on modernity) and de Man (as a close friend and colleague) symptomatic of a larger problem with deconstruction itself—namely, that its flamboyant and hermetic practitioners were at best, intellectual charlatans who had come to defile the West’s most preciously guarded principles (truth, reason, objectivity, liberalism, individualism, history, etc.), and at worst, sympathizers of fascism’s attacks on these same principles (Peeters 393-401).8 For his part, Derrida mounted elaborate analyses of Heidegger and de Man’s writings alongside vehement defenses, not so much of “deconstruction,” but of the university as an institution committed to maintaining norms of discourse that should allow it to address these problems (i.e. debates over fascism’s history and the meaning of “fascism”) better than any other institution.9

A few years after these first “affairs,” the question of the relationship between deconstruction and Heidegger’s Nazism was again raised when scholar Richard Wolin, in his edited volume of essays The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader (1991), published his own translation of “Heidegger, The Philosopher’s Hell”—a 1987 interview Derrida had given with Didier Eribon following the release of Farías’s condemnatory book.10 While the French journal that had first published the interview had granted Wolin permission to undertake the translation, Wolin (according to Derrida and Derrida’s defenders) had not reached out to Derrida to let him know the translation was being done, nor to inform him that it would appear in a book whose introduction, written by Wolin, “comments hostilely” on the interview.11 Derrida’s attempt to forestall the inclusion of Wolin’s translation in subsequent editions of Wolin’s book became public knowledge in 1993, when journalist Thomas Sheehan took to the pages of the New York Review of Books to accuse Derrida of using legal threats to have Wolin’s book impounded. The inflammatory title of Sheehan’s article, “A Normal Nazi,” could be read both as a reference to Heidegger and as an ironic coinage indexing Derrida’s supposed excusing of Heidegger’s Nazism (a charge Wolin and Sheehan agreed on). Yet it could also be read as a pointed attack on Derrida himself. Perhaps, the title blithely suggests, we should think of Derrida, too, as “a normal Nazi.”

Sheehan’s essay precipitated a series of heated exchanges in The New York Review of Books, all published under the handle “L’affaire Derrida” (a perfunctory legal phrase plucked from the subject of a letter sent by Derrida’s lawyers to Columbia University Press, who had published Wolin’s book).12 The attacks and recriminations that ensued testify to the unpleasant acrimony that debates about fascism can provoke in mediated spaces, as well as to their enduring capacity for eruption. Whence, just two years ago (fifteen years after the earlier “affairs”), the re-inflammation of tensions around deconstruction, Heidegger, and Nazism when an academic symposium devoted to Derrida’s essay Geschlecht III again drew anti-Nazi condemnation, only now on Facebook. In their account of this new affair, published in Política Común, Rodrigo Therezo and Adam R. Rosenthal note “the confusion that tends to prevail when [these debates are] reduced to shaming and blaming, as though the issue were so simple as to require an equally simple, and simplistic, solution.” They also comment on the dizzying phenomenon of “accusers [relying] on the very venom they claim to be purging,” or what Derrida called the “mirroring effects” that can take place in the head-to-head combat between fascism and those purporting to oppose it. In other words, the refusal to condemn “fascism” outright and, instead, to think through its more nuanced and complicated ideological and historical structures, can sometimes draw denunciations not all that different from those deployed by reactionary and fascistic regimes. To quote Derrida, reflecting on his own “affairs”:

It is always… in the name of transparent communication and consensus that the most brutal disregard of the elementary rules of discussion is produced (by these elementary rules, I mean differentiated reading or listening to the other, proof, argumentation, analysis, and quotation). It is always the moralistic discourse of consensus—at least the discourse that pretends to appeal sincerely to consensus—that produces in fact the indecent transgression of the classical norms of reason and democracy.

(Derrida in Peeters 400; emphases Derrida’s)

If a moralistic and condemnatory consensus has been reached, one need not wonder how such a consensus has come about.

Gertrude Stein’s path to antifascist denunciation hews remarkably close to these same patterns. Though Stein’s political conservatism and her friendship with the French Americanist scholar and Vichy appointee, Bernard Faÿ, have been common knowledge for nearly a century, condemnations of Stein did not surface in scholarly discussions until 1996. That year, Modernism/modernity published the work of (drumroll…) a graduate student, Wanda Van Dusen, whose (drumroll again…) archival exploration of Stein’s wartime writing turned up an introduction that Stein had written for her own translations of the speeches of Vichy leader and French war hero Philippe Pétain, an unpublished project Stein undertook from 1940-1942. Van Dusen’s essay—which, as one of Stein’s critics helpfully notes, was “written in the wake of the De Man scandal”—portrays Stein as a writer invested in a fetishizing image of Pétain as the “Maréchal” on a white horse, a father figure and “savior” of France.13 Relying on Lacanian psychoanalysis, Van Dusen argues that this image is fetishistic, in part, because it prevents the reality of the persecution of Jews under Pétain’s Vichy government from rising to consciousness in Stein’s text. A “Stein Affair” is surely on the horizon.

While other scholarly explorations of Stein’s wartime life and political commitments (including her Pétain translation project) were published contemporaneously with Van Dusen’s essay (such as Janet Malcolm’s essay “Gertrude Stein’s War Life and Letters,” which appeared in the pages of The New Yorker in 1995, and Edward Burns and Ulla E. Dydo’s appendix essay included in their edited volume of Stein’s correspondence with Thornton Wilder, appearing in 1996), Van Dusen’s condemnatory essay was the work that sparked controversy. Dartmouth scholar Barbara Will—one of Stein’s most exhaustive critics—explicitly frames her research as an extension of Van Dusen’s investigation of Stein’s Pétain translation project.14 In an article from 2004, the 2011 monograph Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma, and in public comments, Will consistently follows Van Dusen in creating a condemning, collaborationist portrait of Stein, criticizing the very idea of Stein’s Pétain translation project and directing inordinate attention toward Stein’s friendship with Faÿ, who—after he was appointed the director of the Bibliotheque Nationale (replacing the Jewish director)—protected Stein, Alice B. Toklas, and their art collection, while working independently with Nazi operatives to expel Jews from the national library and exterminate and deport French Freemasons.15

Though Will sometimes gestures toward a “gray zone” in which Stein (and even Faÿ’s) political leanings might be countenanced—that is, not denounced, given the political and ideological turmoil of the occupation period—her broadly disapproving characterization of Stein’s politics and her friendship with the “tragic” “gay” Faÿ (not to mention the monograph’s selective and tendentiously cropped images) overwhelmingly conveys a vision of Stein to be lamented by readers.16 As critics of Will have noted, Will willfully misreads an ironic comment Stein made (and explained) in a New York Times interview in 1934.17 In this interview, Stein quips that Adolf Hitler should be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize because, “[b]y driving out the Jews, and the democratic and Left elements” (that is, all political opposition in Germany) he has created a repugnant state of “peace” that lacks the requisite elements of difference and competition that keep a state vital. According to Stein, this kind of homogenous state atrophy does not happen in the racially and ethnically diverse United States (Stein and Warren). As Amy Feinstein has it, Stein “attacks Hitler’s ‘peace’ as the equivalent of [national] ‘death’” (184). Yet Will, reading past the palpable irony of the “Nobel Prize” comment (or, as Will has it, suspending the ironic meaning in order to access a “literal” and potentially “deeper meaning”) draws the conclusion that Stein supported Hitler’s eradication of Jewish people from Germany by linking Stein’s use of “peace” in the interview with her comments elsewhere that “peace” is necessary for writers to write (Unlikely Collaboration 71–73). I will set aside that Stein never appears to have expressed a desire to transport her writing career to the peace and quiet of Nazi Germany (rather, around the time of the Time interview, Stein was considering moving back to the United States; see Everybody’s Autobiography 12), as well as the possibility that virtually any writer who relishes peace and quiet might now find themselves on the brink of an affinity with genocide. But I will push back against thedistortions of reading and reasoning that are needed to sustain Will’s condemnation of Stein as a “collaborator.”18 They feel stubborn, as though Stein must be a fascist if we are to have anything useful to say about her. But more importantly, they create confusion where clarity is desperately needed.

By sheer coincidence, two major art exhibitions surrounding Gertrude Stein were mounted in 2010 and 2011, just as Barbara Will’s monograph was sounding alarms about Stein’s “collaboration” with fascism. Organized by and traveling to major cosmopolitan museums (including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art), both exhibitions found themselves coming under attack in the media for “suppressing” Stein’s supposedly right-wing and pro-Nazi political leanings from the explanatory signage patrons often read when viewing exhibitions (Dershowitz, Ellenzweig). These attacks—many of them made by academic scholars—were unequivocal in their denunciation of Stein’s “outright collaboration” with Nazism (Melnikova-Raich), the “work” Stein did “on behalf of France’s Vichy government” (Greenhouse), Stein’s “fascist leanings” (Karlin), her role as “a full-blown Nazi operative” (Dershowitz), and, not surprisingly, her apparently unironic desire to award Adolf Hitler the Nobel Peace Prize (Dershowitz, Melnikova-Raich, Karlin). The same reading of Stein’s “Hitler” interview has appeared in the media as recently as December 8, 2020, on the podcast Bad Gays. Like Barbara Will, one of the co-hosts, Ben Miller, a Berlin-based Queer Studies scholar, interprets Stein’s explanation of the kind of “peace” that Hitler was achieving by racially homogenizing Germany as Stein’s personal desire to see that kind of peace achieved “on the streets” of Germany (34:06). Despite co-host Huw Lemmey’s better interpretation—that Stein saw in American diversity a social vitality not present in Nazi Germany—Lemmey concedes the point, eventually assigning his vote to condemn Stein, with Miller, as “one hundred per cent” a “bad” gay (49:10).19 As Amy Feinstein has noted, Barbara Will’s writing became an authoritative buttress for many of these condemnations, providing a basis for repeated misreadings of Stein’s words and ideas in mainstream media (183). Like Victor Farías’s book on Heidegger, Will’s book has been hailed by antifascist critics as an exposé that tells the suppressed truth about a beloved literary intellectual. Unlikely Collaboration was so uncritically trusted that when The Met agreed to amend their wall signage (under pressure, it is worth noting, from a handful of New York City’s political leaders) The Met also agreed to direct patrons to purchase Will’s book without making any gesture toward evaluating the merits of the claims it made about Stein.20

Yet one has doubts that anyone will actually read Stein—or Will, for that matter. Despite Will’s oddly casual mention of Stein’s confession, “We liked the fascists”—which serves as the epigraph to the present essay—none of the antifascist critiques of Stein that I have come across mention it; not even the Bad Gays podcast.21 But wouldn’t We liked the fascists be enough evidence to write Stein off for those wishing to oppose fascism wherever it rears its ugly head? Why not read Stein’s textin order to gain a better understanding of her pro-Nazi and pro-fascist views, rather than rely on the mediated filter of hearsay and distortions of fact? Derrida similarly felt that, during these kinds of “affairs,” people who were vehemently attacking his work were either intentionally distorting his ideas, misreading them, or not reading them at all. This is a terrifying possibility in conflicts that center on how we judge people’s words, or how we behave in front of spoken and written texts—conflicts that summon the specter of not reading, or advocate outright against reading works by writers whose politics run afoul of the arbiters of public space.

As Edward Burns has noted, antifascist attacks on Stein almost always broach the possibility of banning her work. The antifascist denunciation of Stein, Burns writes, “extends to her literary works. How can one read this writer, they seem to be saying, when she has such odious pro-Vichy, pro-fascist views” (“A Complex Itinerary”). Stein’s critics are well aware of this phenomenon. In her own antifascist critique of The Met’s Stein exhibition, New Yorker contributor Emily Greenhouse consulted Barbara Will on the question of whether to read or not to read Stein. While Greenhouse expresses confidence that we shouldn’t “stop reading” writers like “Heidegger, Eliot, Pound, or even Céline, just because their prejudices were bigoted and their politics abhorrent,” she nevertheless puts the question to Will regarding Stein. In response, Will displays an airy agnosticism. She does not answer Yes. She does not answer No. Instead, Will critiques the “intellectual innocence” of her fellow scholars (a concept she borrows from Frederic Jameson) in order to push back against the cult of personality that she views as supressing important critiques of Stein’s fascism. “I think,” Will warns, “we do need to ask ourselves whether our writers and artists should be judged by higher ethical and moral standards” (Greenhouse). While I do understand where Will is coming from (and I admit to sometimes feeling the desire to immunize my favorite writers against criticism), I nevertheless find it worrying that, in the name of dispelling the aura of genius that supposedly protects and therefore collaborates with fascist collaborators, Will is content to leave on the table the teetering possibility of not reading Gertrude Stein. Anymore? Ever? The abyss yawns.

Amy Feinstein’s Gertrude Stein and the Making of Jewish Modernism, published last year (2022),is a comprehensive and welcome rebuttal to Barbara Will, and to the cyclone of “antifascist” criticism that has swirled around Stein for the last two decades. Feinstein’s monograph is exceptional for its self-consciously patient and ecumenical reading of Stein’s wartime writing. It is also frank in its criticism of the distortions Barbara Will’s work has incited around Stein’s perception of Adolf Hitler, arguing rightly that Will’s contention that “Stein admired Hitler,” and claims based on this contention, “have no sound basis” (183). As Feinstein demonstrates, “Stein consistently and enthusiastically criticizes Hitler in her [wartime] writings” (184)—a claim I will soon lend support to with my own readings of Stein. By critiquing misleading “antifascist” critiques of Gertrude Stein made, ironically, in the name of historical accuracy and transparency, Feinstein performs precisely the kind of anti-antifascism that this essay has been tracking.22

Stein’s Critique of Fathers

I turn now to Stein’s well-known critique of “fathers” in order to follow the threads of Stein’s thoughts as they navigate the Scylla and Charybdis of fascism and patriarchy. As will become evident, it is this schism in Stein’s own thought that leads to a certain contradiction in her opposition to fascism. It is also a place in Stein’s text that has been distorted by a “antifascist” readings. In Everybody’s Autobiography—the same text in which Stein proclaims to “like the fascists” and, in my reading, the only of Stein’s texts Derrida cites at length—we find Gertrude Stein resisting fascism and antifascismalong feminist lines. Much like Virginia Woolf’s critique of “the power of fathers,” Stein folds her critique of fascist leaders into a broader critique of patriarchy via the metonym “fathers.” “Fathers,” according to Stein, are a “depressing” plurality, a corporation of male leaders monopolizing power in order to control the lives of others (137). Thus, Stein did not only associate fathering with the fascist regimes of the time. She also called out fathering across the political spectrum in ways that, admittedly, can feel unnuanced:

There is too much fathering going on just now and there is no doubt about it fathers are depressing. Everybody nowadays is a father, there is father Mussolini and father Hitler and father Roosevelt and father Stalin and father Lewis and father Blum and father Franco is just commencing now and there are ever so many more ready to be one. Fathers are depressing.

(137)

I want to pause over Stein’s grouping of male proper names in this passage. Stein’s inclusion of Mussolini, Hitler, and Franco in this group of “fathers” feels apropos.23 On those counts, her critique of fathers can be interpreted as antifascism. We might also accept Stein’s inclusion of Stalin in this corporation of “fathers,” given the realities of state violence under Stalin’s totalitarian government.

Yet it feels difficult to endorse Stein’s yoking of historical icons of fascism and totalitarianism with liberal and leftist leaders, such as the American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Léon Blum, the socialist leader of the Popular Front who became the first Jewish Prime Minister of France while Stein was writing Everybody’s Autobiography. Insofar as Roosevelt and Blum can be thought to have fought against fascism, Stein’s critique of them would appear to resist antifascism in a sense I do not advocate for. Even if I agree with her feelings about fathering, surely there are important differences between these “fathers” and their styles of parenting. I’m prompted to argue: Not all dads are “fathers.”

Nevertheless, I wish to follow Stein’s thoughts a little further to survey how Stein asks us to envision “fathers” from a feminist perspective. For one thing, Stein’s critique of depressing fathers spans global history. For Stein, fathering is a force that can make or break a century. When there is fathering, Stein contends, life pretty much sucks for everyone: “As I say fathers are depressing any father who is a father or any one who is a father and there are far too many fathers now existing. The periods of the world’s history that have always been most dismal ones are the ones where fathers were looming and filling up everything” (137). In another passage, Stein elaborates on the popularity of the becoming of fathers and the eventual resistance to fathers, across Western history:

Sometimes barons and Dukes are fathers and then Kings come to be fathers and churchmen come to be fathers and then comes a period like the 18th century a nice period when everybody has had enough of anybody being a father to them and then gradually capitalists and trade unionists become fathers and which goes on to communists and dictators, just now everybody has a father…

(146)

Stein’s narrative of human history toggling between wanting and not wanting fathers hews remarkably close to a historical materialist view of the world.24 But instead of the history of class struggle, Stein asks us to think of world history as the history of sexual struggle, in which communism arrives not as the transcendence of the dialectic, but as one among perhaps infinite stages of conflict between fathering and the resistance to fathering. In the twentieth century, “everybody has a father” because men (and perhaps “any one”) across political and social strata have decided to become “one”—that is, “a father.” I find it difficult not to identify a little with Stein’s commentary on what we might think of as geopolitical manspreading over time. Would not many of us credit, in large part, the “depressing” events of the past ten years to the worldwide renaissance of political strongmen, the rise in right wing popular support for them, and the political alliances they have been making across the globe? Thus, while Stein may be painting with broad strokes, a recognizably depressing “father” figure does appear on her canvas.

Importantly, Stein’s political critique of fathers is grounded in personal testimony as a Jewish woman: “I had a father, I have told lots about him in The Making of Americans but I did not tell about the difference before and after having him” (Everybody’s Autobiography 137). Stein is referring to her father, Daniel Stein, who, according to Stein, asserted patriarchal control over the Stein family. Like Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein expressed feeling a sense of freedom when her father died: “Then our life without a father began a very pleasant one. // I have been thinking a lot about fathers any kind of fathers” (146). While Stein situates her critique of fathers within her personal testimony about being raised by one, and while all of the examples Stein gives of fathers are men, Stein’s use of the neutral pronouns “everyone,” “any kind,” and “any one” leaves room for thinking of “fathers” as a modality of relation that assumes economic, political, and domestic domination of others as its primary goal, and which anyone (or “any one” in Stein’s phrasing) can embody or lend support to, including women. As a genre that is not one, there are any kinds of fathers and fathering, and anyone can be one. Stein thus radicalizes “fathers” so that it becomes a signifier naming an ever-widening patriarchal corporation not limited by gendered, political, geographic, or religious boundaries.

This might explain Stein’s willingness to critique patriarchy within Jewish tradition despite the role antisemitism was playing in fascism’s populist appeal during the time she was at work on Everybody’s Autobiography. Here is Stein again: “The Jews they come into this because they are very much given to having a father and to being one and they are very much given not to want a father and not to have one, and they are an epitome of all this that is happening the concentration of fathering to the perhaps there not being one. / Well anyway…” (146-147). If Jewish people are “very much given to having a father” and “to being one” (that is, to being a father), they are also prone “not to want a father and not to have one” (that is, not to have a father). Likewise, if Jewish people are “the epitome” of “the concentration of fathering,” they are also the epitome of the possibility of “there not being one” (that is, there not being a father). The Jewish resistance to fathering that Stein marks in this passage could index two forms of anti-fathering resistance. On one hand, not wantinga father could refer to Jewish women’s resistance to patriarchy within Jewish community. Stein certainly would have counted herself among Jewish feminists opposed to the control of women’s lives by the patriarchal norms of Jewish tradition. On the other hand, “being very much given not to want a father”—when read in relation to Stein’s inclusion of Hitler as a contemporary icon of “fathering”—could also point to Jewish political resistance to state antisemitism. Thus, as the “epitome” of the dialectic between patriarchy and feminism that Stein observed playing out on the world’s stage during the 1930s, Jewish tradition mirrors the paradigm of depressing fathering evident in human societies more broadly. More importantly, Jewish community also gives rise to resistance to fathering, whether by fighting back against antisemitism, or by resisting patriarchy’s depressing impact on the lives of Jewish women.25

I will pause to address Barbara Will’s interpretation of this passage in Unlikely Collaborators, in which Will trundles out this passage to support her view of Stein as being ashamed of her Jewish heritage. Reading the same passage, Will argues that Stein “decried” Jews for “their ‘concentration of fathering,’” and that, for Stein, Jews were “the worst malefactors” of fathering’s attempt to control other people’s lives (Unlikely Collaboration 95). Will reads “epitome,” here, hyperbolically and one-sidedly, solely in relation to the “concentration” of fathering, rather than as the back-and-forth between wanting and not wanting fathers that, according to the letter of Stein’s words, Jewish community exemplifies. Will also misreads Stein’s use of the pronoun “one” in this passage, in which (in my reading) Stein consistently links “one” with “father.” Without explanation, Will claims that “one” in the phrase “perhaps there not being one” means perhaps Jews not being Jewish anymore. Here’s Will: “it is not just fathers who are to be purged from [Stein’s vision of the] future/past; chillingly, this sentence also seems to be anticipating a moment where both fathering and the Jews may end up ‘not being one’” (47). Will then claims that this passage represents Stein’s “eerily prophetic” endorsement of the eradication of Jews signaled by the Kristallnacht pogrom, which would not occur until one year after Stein wrote the passage in question (47-48). Such a “reading” is so far out of bounds of scholarly norms, I do a double-take every time I read it, and I wonder why I spend so much time with Will’s work (considering her arguments across two essays and a monograph, genuinely learning from her in-depth historical research, doubting my own faggotty obsession with Stein) when Will seems so casually to dispense with reading Stein in order to denounce her as a Hitler-loving fascist who supported the Final Solution.26 If we read Stein, carefully, considerately, her feminist take on fathering and its relation to Jewish identity is clear, if complex. Jewish community epitomizes the back and forth of “fathering” and non-fathering, that is, the institution of and resistance to patriarchal authority as it manifests itself historically in all kinds of political states—fascist, liberal, or communist.

While Stein’s feelings about fathers are generally pessimistic, she nevertheless envisions a possible reprieve from fathering’s stranglehold in a way resonant with Eve Sedgwick’s negative mnemonic injunction that we “forget” the paternal logos. “[Perhaps],” Stein speculates, “the twenty-first century like the eighteenth century will be a nice time when everybody forgets to be a father or to have been one” (146).27 For Stein, and perhaps for Sedgwick, paternalistic fathers might go away if only people will forget about them. Stein’s prognostic vision of a twenty-first century that has forgotten the desire for fathers—the desire to be or to have one—is a bittersweet wish to dwell upon, given current world affairs. In many ways, the “nice time” that Stein hoped the twenty-first century would have feels further away than ever.

For my part, I do take issue with some of Stein’s thinking around these problems, and her deep-seated though eventually waning support of Philippe Pétain. In my reading, Stein’s error is not that she was a fascist or a “full blown Nazi operative.” Rather, she seems unable to have foreseen the numerous ways that Philippe Pétain, and right-wing political philosophy generally, represented and enacted the kind of persecutory fathering she elsewhere spoke out against. I also agree with Will that Stein’s denial in a letter about Faÿ’s participation in the denunciation of Freemasons displays a willful ignorance that bears holding Stein to account (181). Stein was likely well aware of Faÿ’s anti-masonic feelings, and she would have known that Freemasons, like Jewish people, were targets of right-wing persecution. Moreover, Stein’s casual celebration of slave-owning 18th century European republics as utopian societies-without-fathers also betrays the committed resistance to fascistic violence that she displays elsewhere. That said, Stein’s critique of fathers remains of interest insofar as it touches on a historically salient elision of feminist concerns from the fields of progressive and antifascist politics–an elision Derrida will also interrogate when he turns his thought toward Nietzsche, and Nietzsche’s desire for an academic “Führer.”

Derrida’s Critique of Führers

As scholars have noted, Derrida’s meditations on the relation between fascism and philosophy predates the Heidegger and de Man “affairs” that, according to some of Derrida’s detractors, exposed deconstruction as a rearguard defense of historical fascism. One such work is the essay “Otobiographies: The Teaching of Nietzsche and the Politics of the Proper Name.” Originally written as the second session of Derrida’s 1976–77 university seminar (published recently in English translation as Life Death [2020]), this essay was delivered in English translation in 1978 and went on to appear in The Ear of the Other (1988) with “minimal” yet notable differences from the seminar.28 Uniting the essay and the seminar on which it is based is Derrida’s extended thinking of the relationship between education, philosophy, auto/biography, and Nazism. Like the seminar, the essay juxtaposes two of Nietzsche’s texts—the autobiographical Ecce Homo (1908) and the early or “youthful” lecture On the Future of Our Educational Institutions (1872)—in order to take stock of the legacy of the Nietzschean text, which, as Derrida stresses, served as a recurrent reference point and philosophical cornerstone for National Socialism in Germany; a problematic fact that Derrida also links to Heidegger (“Otobiographies” 29; Life Death 44). Already in this essay, Derrida is concerned about the “mimetic perversion,” or mirroring effects, in play both in Nietzsche’s text and in debates about fascism and antifascism in relation to Nietzsche’s text (“Otobiographies” 31).29

I want to underscore that Derrida’s stress in this essay is not to acquitNietzsche or Nietzsche’s text from the history of its destination as a resource for Nazism. Derrida refuses simply to dismiss the allegations that there might be something fascistic about Nietzsche’s philosophy. But neither does Derrida allow for simply accepting right-wing interpretations of Nietzsche that would presumably support something like the establishment of a fascist state. Turning to Nietzsche’s early writings on the German university, Derrida keeps Nietzsche’s text on the hook, so to speak, wondering why “the only teaching institution… that ever succeeded in taking as its model the teaching of Nietzsche on teaching will have been a Nazi one” (“Otobiographies” 24; Life Death 41).30 “There is nothing absolutely contingent,” Derrida continues later, “about the fact that the only political regimen to have effectively brandished [Nietzsche’s] name as a major and official banner was Nazi” (“Otobiographies” 31; Life Death 46). In short, Derrida is willing to interrogate Nietzsche’s thought in order to consider what in the text might authorize a Nazi or fascist interpretation of it, and he does so by turning attention to the word “Führer” as it appears in Nietzsche’s early treatise on education.

In German, Führer is the common word for “leader,” but can also mean “driver” or “guide” (“Führer”). Importantly, its appropriation by Hitler and the Nazis, and its collapse into a demagogic singularity—Der Führer, the Führer, the one and only leader—stands as emblematic of the conflation of führers and fathers articulated by feminists like Woolf and Stein. The homophonic resonance between Führer and father, in other words, is more than just wordplay across faulty etymology and the abysses of translation. Führers and fathers collaborate across idiomatic and geographical borders, co-constructing the image of a male dictator whose arrival promises the restoration of law and order, the rigidification of borders, cultural and ethnic homogeneity, spiritual alignment, and the subsequent regeneration of the nation via the paternal logos—in short, the building blocks of a fascist mythos. Along these lines, Derrida interrogates Nietzsche’s insistence that the problem with the modern university, and what leaves it open to the feminizing forces of decay, is that it is missing a leader, or, to use Nietzsche’s word, a Führer. Here is Derrida paraphrasing Nietzsche: “The whole misfortune of today’s students… can be explained by the fact that they have not found a Führer. They remain führerlos, without a leader” (“Otobiographies” 28). Not unlike Stein’s vision of a leaderless France in her introduction to the Pétain translations, Nietzsche diagnoses the German university’s lack of vitality as the logical result of another lack–the lack of a leader, or Führer.

Rather than exculpating Nietzsche’s text from its eventual complicity with the Nazi institutionalization of this word, Derrida ask us to give Nietzsche’s Führer a thorough hearing:

Doubtless it would be naive and crude simply to extract the word “Führer” from this passage and to let it resonate all by itself in its Hitlerian consonance… as if this word had no other possible context. But it would be just as peremptory to deny that something is going on here that belongs to the same (the same what? the riddle remains), and which passes from the Nietzschean Führer, who is not merely a schoolmaster and master of doctrine, to the Hitlerian Führer, who also wanted to be taken for a spiritual and intellectual master, a guide in scholastic doctrine and practice, a teacher of regeneration.

(“Otobiographies” 28)

In other words, there is not nothing going on between Nietzsche’s call for a Führer and Hitler’s answer to that call. Some “same” runs between Nietzsche and the Nazis as they fantasize about a Superman, or, heroic figure of rescue.

Interestingly, this is precisely where Derrida’s essay departs from the text of the Life Death seminar. In the essay, Derrida’s questioning of “the same” that runs between Nietzsche’s umbilical cord, the university, and the state leads him to a feminist reflection on the absence of women in Nietzsche’s university. It is this absence of women that juts out, like a phallocentric spur, in the Nietzschean text. Resisting the temptation to identify with the prophetic and perhaps antifascist image of Nietzsche’s university to come made up of professors who are “knights of a new order” and “mischief-making students” (37), Derrida pauses to mark this absent presence:

Yet, even if we were all to give in to the temptation of recognizing ourselves, and even if we could pursue the demonstration as far as possible, it would still be, a century later, all of us men—not all of us women—whom we recognize. For such is the profound complicity that links together the protagonists of this scene and such is the contract that controls everything, even their conflicts: woman, if I have read correctly, never appears at any point along [Nietzsche’s] umbilical cord, either to study or to teach.

(38)

In a text that is palpably antifascist, Derrida astutely links Nietzsche’s discourse, and the Nazi discourse that claims Nietzsche as an ur-source for education, to the phallogocentric exclusion of the feminine. Thus, even if we can glean an antifascist Nietzsche from his text, what remains to be interrogated is the fascist-like suppression of women. In other words, the erasure of women is perhaps this “same” that resonates between the Nietzschean Führer and the Nazi Führer, and produces the depressing conditions of feminist resistance–—as with all ages in which people can’t stop remembering to be or to want “fathers.” Between Stein and Derrida, then, feminism figures as a point of resistance to both fascism and an antifascism that fails to interrogate phallogocentrism.

Archive Fever

There is, however, more to the Derrida/Stein connection than the mere coincidence of their affairs, or their mutual interest in interrogating the double exclusion of the feminine in war between fascism and antifascism. While I have written about this elsewhere, it bears reiterating that Derrida was aware of Stein’s status as an important feminist and modernist figure, that he read her work, and that he cited Everybody’s Autobiography in one of his most personal essays, “Circumfession” (1993) (“Writing in Cars”). Derrida also cited Stein’s proper name on at least two other occasions. In the interview “This Strange Institution Called Literature” (1992), Derrida includes Stein in a list of “immensely great modern writers” along with Virginia Woolf (59). Then in The Animal That Therefore I Am (2008) (originally published French in 2006), Derrida refers to Stein as one of many well-known literary “autobiographical animals”—again along with Woolf (49). All in all, Stein appears to have been a meaningful literary and cultural touchstone for Derrida during the last two decades of his life.

Yet Stein’s name, writing, and politics had touched Derrida as far back as his childhood in French-occupied Algeria. In 1940—when “Jackie” Derrida was ten years old—Philippe Pétain made an armistice with Adolf Hitler, effectively avoiding direct war, but conceding political authority in continental France to the Nazis. Like many people living in France at the time, Stein thought Pétain’s capitulation “saved” France from utter destruction (Burns). Though her feelings toward Pétain degraded over time, Stein remained adamant that the armistice helped France “win” in the long run (see “The Winner Loses” and Wars I Have Seen). But while Gertrude Stein was championing Pétain and mounting the project of translating his speeches into English (with the express purpose of convincing Americans to support Pétain’s regime), Pétain and Vichy passed a series of antisemitic laws without any pressure from Nazi leadership.31 These laws, defining Jews as a distinct “race,” instituted quotas on Jews holding public and professional positions, as well as the number of Jewish students who could be admitted to French public schools. Then on October 7, 1940, Vichy rescinded the Crémieux decree, thus stripping French citizenship from Jews living in French colonies—including a ten-year-old Derrida. The rise of Vichy also led to a more rapid institutionalization of antisemitism in Algeria, whose colonial leadership consistently went further in persecuting Algerian Jews (Peeters 19). Thus, in 1942—while Stein was still devoting creative energy to celebrating Philippe Pétain—Pétain’s regime and supporters passed measures resulting in Derrida’s expulsion from the French school he was attending in colonial El Biar.

It was during this tumultuous time, according to Derrida’s biographer Benoît Peeters, that Derrida began to develop a love of literature, in large part due to the presence in Algeria of French literary giants, such as Albert Camus and Andre Gide (18, 29, and passim). Algeria was flush with French literary culture in the 1940s, with “Algiers [becoming] a sort of second French cultural capital at the end of the war” (29). Progressive Algerian-based publisher Edmond Charlot, who had introduced Camus to the French readership, was instrumental in disseminating politically dissident and anti-Vichy writing during the war, including modernist works of the American and English avant-garde. Importantly, between October of 1940 and the summer of 1944, Charlot published several French translations of Gertrude Stein’s works, including a piece called “Mort est” (or “Death Is”), in the journal Fontaine. As Peeters reports, during this time Derrida was an avid reader of “literary supplements and reviews, sometimes [reading them] out loud” (29). (Derrida was also writing and submitting poetry at this time.) It seems probable, then, that before Derrida was even a teenager, he would have read Gertrude Stein—possibly out loud—in French translation.32 In other words, “Circumfession”might not have been the first or only time Derrida tried to import Stein’s voice into his own. Moreover, Derrida would have associated Stein with the political resistance to fascism and antisemitism that he was cultivating as a persecuted Jew in Vichy-era Algeria.

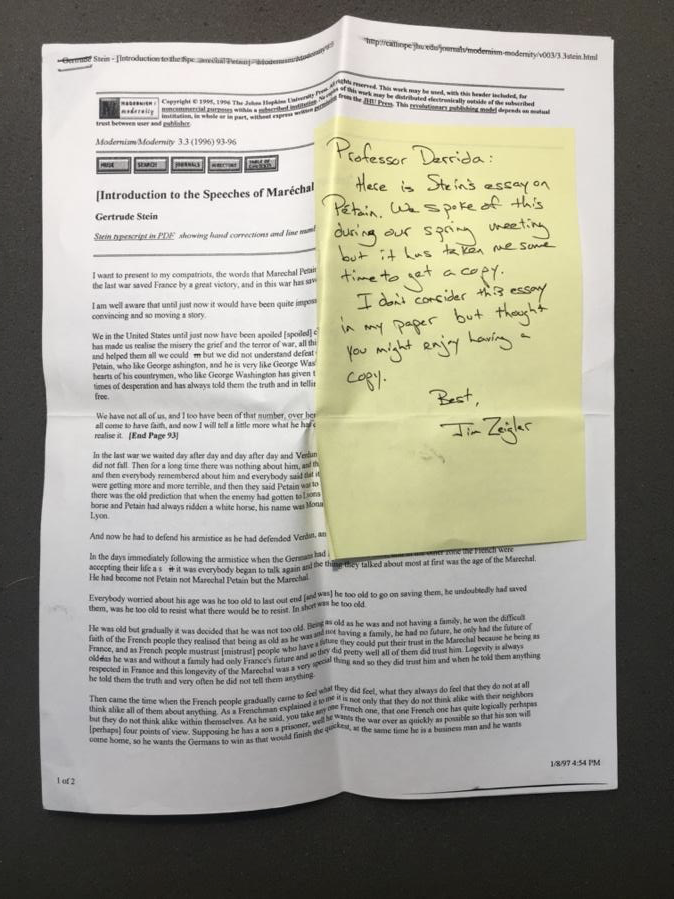

But Derrida did not admire Stein with the “innocence” that some antifascist scholars are keen to strip away from their colleagues. Derrida’s library, held at Princeton University, offers evidence that, later in his life, Derrida was aware of Stein’s support of Pétain, and that the so-called doyen of modernism had become a flashpoint in “scholarly” arguments over fascism. Derrida’s library actually includes a copy of Stein’s “Introduction” to the Pétain speeches that Wanda Van Dusen’s research brought to light. The printout of Modernism/modernity’s1996 reproduction of Van Dusen’s typescript appears to have been given to Derrida by a student, Jim Ziegler. Attached to the printout is an adhesive note that reads: “Professor Derrida: Here is Stein’s essay on Pétain. We spoke of this during our spring meeting but it has taken me some time to get a copy. I don’t consider this essay in my paper but thought you might enjoy having a copy” (Fig. 1). Dated January 8, 1997, the printout and accompanying note suggest that Derrida had discussed Gertrude Stein’s support of Pétain in a scholarly context around the time Stein’s “Introduction” was made public in 1996. Derrida’s mention of the repeal of the Crémieux decree in 1997’s De l’hospitalité, and his mention of Stein in the 1997 Cerisy lecture that became The Animal That Therefore I Am, might thus be read anew in light of Derrida’s knowledge of Stein’s pro-Pétain writings.

Fig. 1. Printout of Modernism/modernity’s reproduction of Stein’s introduction to the Pétain speeches. The Library of Jacques Derrida, Studio Series, RBD1, Rare Book Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

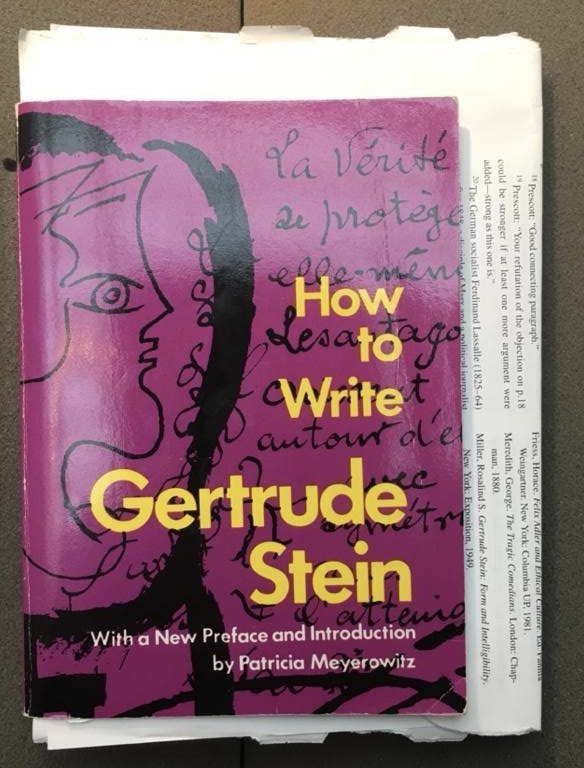

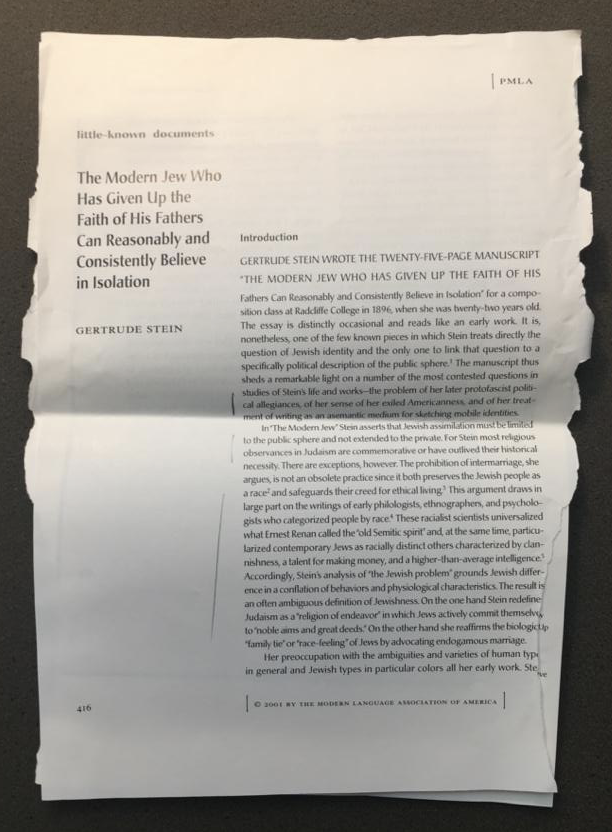

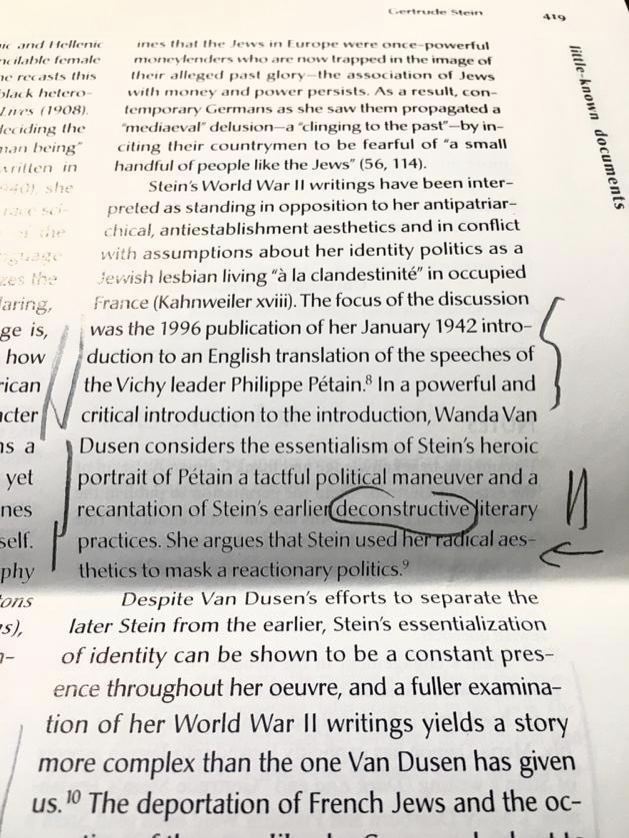

Derrida also knew that Stein was being criticized for disguising her purported right-wing sympathies with literary experimentalism. An annotated printout of Amy Feinstein’s 2001 introduction to an early Stein essay can be found in Derrida’s library inserted into a copy of Stein’s How to Write (1931) (see Figs. 2, 3 and 4).33 One can see that Derrida emphasizes Feinstein’s discussion of Wanda Van Dusen’s essay, circling the word “deconstruction” and drawing an arrow that points to the sentence, “[Van Dusen] argues that Stein used her radical aesthetics to mask a reactionary politics” (Fig. 4). These archival traces of Stein’s political support for Pétain, and scholarly critiques of such support, in Derrida’s library suggest that Stein was on Derrida’s mind periodically from childhood through his last years of writing.

Figs. 2, 3 and 4. Derrida’s copy of Stein’s How to Write and Amy Feinstein’s introduction to “The Modern Jew Who Has Given Up the Faith of His Fathers Can Reasonably and Consistently Believe in Isolation.” Gertrude Stein. How to Write; The Library of Jacques Derrida, Studio Series, RBD1, Rare Book Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Yet it was in the 1980s, just on the heels of the three antifascist “affairs”—and nearly a decade before Wanda Van Dusen’s exposé—that Derrida cited Stein’s Everybody’s Autobiography in the work that would become “Circumfession.” Despite the readiness to fight that Derrida exhibited in all three “affairs” he was drawn into, being accused of apologizing for and “collaborating” with fascism also prompted Derrida to produce a more confessional and rhetorically vulnerable text, in which he reflects on the antisemitism of the Algerian colonial government and his childhood expulsion from the French lycée, his childhood fantasies about being a member of the French Resistance, and the accusations he was facing in scholarly and public discussion for not being vigilant enough in the fight against antisemitism and fascism. Derrida began writing “Circumfession” (Circonfession in French) near the end of 1988 and worked on the essay through May 1991. That Derrida turns to Gertrude Stein in this prosopopoeic text suggests that the problems of historical fascism, the role of literature in politics, and a complex relationship with Jewish identity are in large part what drew Derrida to Stein in this moment.

Yet feminism was also coming more to the fore of Derrida’s thought during this same period. In texts like Spurs: Nietzsche’s Styles (1978) (Éperons in French, 1978), Cinders (2014; Feu la cendre in French, 1982), and the interviews “Choreographies” (1982) and “Women in the Beehive” (1987), Derrida progressively addresses feminist problematics more explicitly in his writing.34 His citation of Stein in 1991’s Circonfession could be read as a new feminist eruption along this archipelago of Derrida’s thought. Yet we should also link back Derrida citation of Stein in “Circumfession” to “Otobiographies” and his reading of Nietzsche’s “Führer,” ten years earlier. Derrida’s thought on fascism, and thought against fascism, includes a sustained if occasionally marked thinking of feminism and feminist resistance to “anti”-fascism—that is, an “auntie”-fascism that was influenced to a notable degree by the name, writing, and life of Gertrude Stein.

“Auntie”-Fascism’s Siren

Though the context of the Second World War (with Nazis and Italian Fascists occupying France, not to mention the Stein/Toklas household) prevented Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas from volunteering the same way they had done in the First World War, and while Stein’s own antifascism did sometimes come up short, the spirit of the “Auntie” prevailed, however imperfectly, throughout Stein’s life and career. Stein was not only aware of the plethora of political positions that emerged during fascism’s rise in Europe. She also thought of herself as a thorn in the side of certain fascistic programs and ideals, including its appeal to the strengthening of patriarchy. In “Gertrude Stein Taunts Hitler”—Charles Bernstein’s rebuttal to Barbara Will’s “antifascist” claim that Stein sincerely wanted Hitler to be awarded a Nobel Prize for “Peace”— Bernstein notes that, in actuality, Stein “associates Hitler with all that is bad in Germany,” and that Stein’s “remarks [in the 1934 interview] constitute an attack on Hitler.” Bernstein’s sense that Stein “taunts”Hitler (rather than applauding Hitler), and his resistance to Will’s willful antifascist reading of Stein, also points to what I have been arguing—that Stein’s “Auntie”-fascism taunts not only fascism, but antifascism; provokes it, dares it to strike, and comes to its aid by holding it in suspension. “Auntie”-fascism keeps antifascism alive, sustaining it in a kind of critical condition that it should never hope to recover from.

I also wish to suggest—calling again on Sedgwick—that there’s something queer about this “Auntie,” and the way it navigates binaristic and oppositional positions by opening up an unruly “space of nonconformity.” Somewhere between the depressing regime of “fathers” and a less-depressing but perhaps too symmetrical regime of mothers—between “Father Hitler” and Mother Courage—might lie a cavalcade of aunties; those avunculate pseudo-parents who behave admirably in emergencies, and who arrive with aid via crosswise vectors of kinship. I ask the reader to hear the play between the English word taunt and tante, the French word for aunt. As Sedgwick (citing Proust) has pointed out, tante has been used for a long time among French gay men to refer to sexually receptive partners, as well as “any man who displays a queenly demeanor” (59). Neither a resolutely “bad gay,” nor a gay that is unimpeachably “good,” the “auntie,” or la tante, represents a threshold between oppositional positions, of gender and of politics. Might we attune ourselves to the distant siren, ring, or clang, of this admirable fleet of aunties speeding down the road after they have been called to the scene of a fascist emergency? But by what road? And what ambulance? And who will be behind the wheel? If I may be permitted to pun in French, a language I do not really speak: Vive la résistante!

Notes

- “We liked the fascists” appears in a passage in Everybody’s Autobiography where Stein recounts an exchange she had had with her friend W. A. Rogers as political tensions were rising in Europe following both the onset of the Spanish Civil War and fascist Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia (318). For an extended discussion of the exchange of corn between Rogers and Stein, see Janet Malcolm, in references. ↩︎

- For a gloss of the concept of “nadir” in African American cultural history, see Mitchell, in references. ↩︎

- In Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook (2017), Mark Bray insists that antiracism is a desideratum of modern antifascism. Conversely–and citing Robert Paxton’s “The Five Stages of Fascism” (1998)–Bray views Black activist and journalist Ida B. Wells’ campaign against lynching as an example of a proto-antifascism (6). See Bray, in references. For more on the African American response to the second Italo-Abyssinian conflict, see: John Cullen Gruesser, Black on Black: Twentieth-century African-American Writing about Africa. University Press of Kentucky, 2015; William R. Scott, “Black Nationalism and the Italo-Ethiopian Conflict 1934–1936,” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 63, no. 2, 1978, 118–134; Ivy Wilson, “‘Are You Man Enough?’: Imagining Ethiopia and Transnational Black Masculinity,” Callaloo, vol. 33, no. 1, 2010, 265–277; Nadia Nurhussein, Black Land: Imperial Ethiopianism and African America. Princeton UP, 2019, 7; Robert A. Hill, “Ethiopian Stories: George S. Schuyler and Literary Pan-Africanism in the 1930s,” South Asia Bulletin, vol. 14, no. 2, 1994; and Ryan Tracy, “‘To Work Black Magic’: Richard Bruce Nugent’s Queer Transnational Insurgency.” JAm It! (Journal of American Studies in Italy), vol. 1, 2019. ↩︎

- For the sake of time, I will have to postpone a comparative reading of Stein’s “aunts” and the “ants/aunts” of Derrida’s Fourmis. See “Ants,” in references. ↩︎

- See Stein’s Everybody’s Autobiography (10-12, 22). For a critique of Stein’s Asian imaginary and Stein’s concept of the “peaceful penetration of Europe,” see Teo, in references. For Stein’s view that Europe “is finished,” see Everybody’s Autobiography (22). ↩︎

- I will confess that one of Stein’s detractors has already beaten me to the “auntie”/”anti” pun. See Allen Ellenzweig’s “Auntie Semitism at the Met.” ↩︎

- In his biography of Derrida, Benoît Peeters quotes a Newsweek article from 1987 that claimed there were “grounds for viewing the whole of deconstruction as a vast amnesty project for the politics of collaboration during World War Two” (393). Wanda Van Dusen’s essay on Stein’s introduction to her Phillipe Pétain speech translation project (which I will discuss later) is the first sustained academic antifascist critique of Stein. In it, Van Dusen argues that Stein “masks” the fascistic agenda of Pétain’s government. See Van Dusen, in references. ↩︎

- A future exploration of the resonance between deconstruction’s critique of Western metaphysics and Stein’s notion of the “Oriental” “peaceful penetration” of the West might bear fruit. ↩︎

- For what it’s worth, Derrida had already begun reading Heidegger’s philosophy in relation to German National Socialism at the time that the “Heidegger Affair” broke. Derrida had devoted four years of seminars to the question of Nazism and Heidegger’s philosophy, culminating in Of Spirit, published in French in 1987—the same week Farías’s book came out (Peeters 394). See also Peggy Kamuf’s comment in the interview “The Work of Intellectuals and the Press” that “there was almost nothing in Farías’s book that constituted revelations for those who… had for decades been coming to terms in their own writing, with the implications of Heidegger’s political engagements in 1933-1945 and beyond” (“The Work of Intellectuals” 422). ↩︎

- For the purposes of disclosure, I took a seminar with Richard Wolin at The CUNY Graduate Center. ↩︎

- See Didier Eribon’s contribution in “L’Affaire Derrida’: Another Exchange,” in references. ↩︎

- In his defense of the title, Thomas Sheehan argued it had simply been borrowed from the letter from Derrida’s lawyer, which was sent with the subject “AFFAIRE: DERRIDA / N. R.: 1251.” (“L’Affaire Derrida”). See all the three articles published under the “L’Affaire Derrida” title, in references. ↩︎

- In a footnote, Barbara Will situates the Stein scandal within the “wake” of the one surrounding Paul De Man (Unlikely Collaboration, 209, n.30) ↩︎

- According to Will, it was not until 1996 when, “an American graduate student named Wanda van Dusen began raising uncomfortable questions about an unfinished manuscript that few knew about and no one had really confronted” (Unlikely Collaboration 11). ↩︎

- In my reading, no scholars have critiqued the homophobic overtones of Will’s work on Faÿ, such as her portrayal of the “new orientation” of Stein’s salon once it had been supposedly overrun by queer men. Replacing more serious artists such as Sherwood Anderson, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Hemingway, were, according to Will, “a different set of artists, writers, and assorted hangers on.. [including] men such as Faÿ, Virgil Thompson, Carl van Vechten, Hart Crane, Paul Bowles, Aaron Copland, Georges Hugnet, Francis Rose, the artist Pavel Tchelitchew and his partner Charles Henri Ford, and the surrealist writer René Crevel, who ‘talked with a pronounced lisp’… Almost all of these ‘disciples’—Carl Van Vechten’s words—were homosexual or bisexual, and the electric atmosphere of the salon reflected this new orientation” (24-25). See also footnote 91 on page 215, in which Will further comments on the “‘decline’” of Stein’s salon. ↩︎

- For Will’s “gray zone,” see Unlikely Collaboration, pp. xv, 162, and 174. ↩︎

- See Jacket 2, and Feinstein. ↩︎

- Will: “Yet despite all of these dangers and uncertainties, and even after Vichy had ceased to be a viable political entity, Stein remained its unlikely collaborator” (Unlikely Collaboration 138). ↩︎

- Miller also repeats the claim that Gertrude Stein knew of the deportation of thirty Jewish children who were being sheltered in an orphanage “in her town.” Edward Burns and Amy Feinstein have pushed back against this claim, noting that the children were being hidden in a town at least 20 kilometers from where Stein was living, and that, out of the necessity to keep the children’s location a secret from the Nazis, few people (including Stein) would have known about it. See Burns (“A Complex Itinerary”) and Feinstein (Jewish Modernism). ↩︎

- As Feinstein notes, The Met’s website now directs viewers to Charles Bernstein’s Jacket 2 dossier on the scandal surrounding Stein’s politics. For political leaders condemning The Met, see Greenhouse (“Why Won’t the Met”) and Feinstein (Jewish Modernism 242-43, n.1). ↩︎

- Will, Unlikely Collaboration,132. ↩︎

- See Dershowitz’s complaint that “[by] withholding from the viewers an important part of the truth the Met is engaging in a falsification of history.” Or Will’s positioning of her project as oppositional to scholars who oversimplify, and therefore distort, Stein’s “complex character and the historical moment in which she and her fellow modernists lived” (“The Strange Politics”). ↩︎

- Stein’s inclusion of “Father Franco” should act as a counterweight to the circulating claim that Stein supported Franco’s fascistic takeover of the Spanish republic. See Melnikova-Raich and Ellenzweig, in references. ↩︎

- During the 1930s and 40s, Stein evinced a sharp understanding of the historical and material development of modern history. See, for instance, Brewsie and Willie (1945), in which an American GI educates his friends with a brief gloss of this epochal history of modern states (733). ↩︎

- See also Stein’s early essay “The Jew Who Has Lost the Faith of His Fathers Can Reasonably and Consistently Believe in Isolation,” where Stein credits Jews (such as Karl Marx) for having the potential to be great revolutionary leaders. ↩︎

- I do apologize to the reader if I have allowed myself to be carried away by my own emotions. I hope it is clear why I feel the need to militate against these unrestrained misreadings of Stein’s texts. ↩︎

- The strongest aspect of Barbara Will’s work on Stein and fascism lies in her edification of the significance of Stein’s valorization of the “eighteenth century” as a supposed time without fathers (48–51). Will is right to contextualize Stein’s interest in the 18th century within the intellectual discourse on the agrarian politics of the 18th century often associated with the “Founding Fathers” of the United States. Nevertheless, while Will attributes Stein’s rosy view of the 18th century to the influence of Faÿ, Stein was not the only modernist intellectual who considered 18th century agrarianism as the origin of, and model for, modern democracy. (For more in agrarian politics and modernists, see Fiona Green, in references.) Moreover, Will repeatedly attributes to Stein an anxiety over social decay, or “decadence”—a term that circulated throughout the 1930s and held many different meanings for different people. Of the more than two dozen occurrences of the word “decadence” and variations of it in Will’s book, none of them is linked to something Stein wrote herself. In my own reading, I have not found any place Stein uses this word as a pejorative term against the evils of modern society. ↩︎

- Pascale-Anne Brault and Peggy Kamuf note that the essay derived from the seminar appeared “with minimal reworking” (Life Death xiii). ↩︎

- The phrases “reactive inversion” and “possibility of perversion or inversion” are used in the corresponding passage of Life Death, although this may just be a variation in translation(46). ↩︎

- Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas translate this passage from the seminar as “And why, in the end, has the only institutional initiative to which Nietzsche’s teaching on teaching given rise be Nazi?” (41). ↩︎

- Derrida himself commented on the antisemitic zeal of the Vichy government in Of Hospitality: “Access to French citizenship was made faster for indigenous Jews [living in Algiers] by the famous Crémieux decree of October 24, 1970, which was then abolished by Vichy, without the slighted intervention or demand on the part of the Germans, who at the time only occupied a part of (European) France” (143). See also Burns, and Peeters (17). ↩︎

- There is an extant copy of Fontaine in the “Studio Series” of Derrida’s library. Published in 1944, the issue appears to be a review of English-language modernist literature from 1918-40. Though none of Stein’s texts appear in this issue, Stein’s name is mentioned at least three times and in discussions of new developments in avant-garde Anglophone literature. See “Aspects de la littérature,” in references. ↩︎

- Derrida also owned a French translation of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas published in 1965 by Lucien Mazenod in the series Les Maîtres du XXe Siècle. Gertrude Stein. Les Ecrivains célèbres. Gertrude Stein; The Library of Jacques Derrida, House Series, RBD1-1, Rare Book Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library. ↩︎

- It feels important to note that Derrida cites Woolf’s Three Guineas in Cinders (49), suggesting—along with Derrida’s citation of Stein in Circumfession—that feminism was strongly tied to Derrida’s reflections on fascism and resistance to fascism. See Cinders, in references. ↩︎

Works Cited

- “Aspects de la littérature anglaise de 1918 à 1940” (numéro spécial); The Library of Jacques Derrida, Studio Series, RBD1, Rare Book Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

- Bernstein, Charles. “Gertrude Stein taunts Hitler in 1934 and 1945: (Sieg heil, sieg heil, right in der Fuehrer’s face.)” Jacket 2, 9 May 2012. https://jacket2.org/article/gertrude-stein-taunts-hitler-1934-and-1945. Accessed 31 Dec., 2022.

- Bray, Mark. Antifa: The Anti-fascist Handbook. Brooklyn: Melville House, 2017.

- Burns, Edward. “Gertrude Stein: A complex itinerary, 1940–1944.” Jacket 2. 9 May, 2012, https://jacket2.org/article/gertrude-stein-complex-itinerary-1940-1944. Accessed, 31 Dec., 2022.

- Burns, Edward, and Ulla E. Dydo. “Gertrude Stein: 1942–1944.” In The Letters of Gertrude Stein and Thornton Wilder. Edited by Edward Burns and Ulla E. Dydo, with William Rice. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996, 401–421.

- Derrida, Jacques. The Animal That Therefore I Am. Edited by Marie-Louise Millet. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

- —.“Ants.” Oxford Literary Review, vol. 24, no. 1, 2002, 19–42.—. Cinders. Translated by Ned Lukacher. University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

- —.“Choreographies.” In Points…: Interviews, 1974-1994. Edited by Elizabeth Webber. Translated by Peggy Kamuf et al. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995, 89–108.

- —.“Circumfession.” In Jacques Derrida. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993.

- —. Life Death. Edited by Psacale-Anne Brault and Peggy Kamuf. Translated by Pascale-Anne Brauly and Michael Naas. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2020.

- —.“Otobiographies: The Teaching of Nietzsche and the Politics of the Proper Name.” The Ear of the Other : Otobiography, Transference, Translation : Texts and Discussions with Jacques Derrida. University of Nebraska Press, 1988.

- —. Spurs: Nietzsche’s Styles. Translated by Barbara Harlow. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978.

- —. “This Strange Institution Called Literature.” Acts of Literature. Edited by Derek Attridge. New York: Routledge, 1992, 33–75.

- —. “The Work of Intellectuals and the Press.” In Points…: Interviews, 1974-1994. Edited by Elizabeth Webber. Translated by Peggy Kamuf et al. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995, 422–454.

- Derrida, Jacques, and Anne Dufourmantelle. Of Hospitality. Translated by Rachel Bowlby. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Derrida, Jacques, James Adner, Kate Doyle, and Glenn Hendler. “Women in the Beehive: A Seminar with Jacques Derrida.” differences, vol. 16, no. 3, 2005, 139–157.

- Dershowitz, Alan. “Suppressing Ugly Truth for Beautiful Art,” Huffington Post, May 1, 2012. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/alan-dershowitz/met-gertrude-stein-collaborator_b_1467174.html.