Teresa M. Vilarós

Texas A&M University

Volume 16, 2024

In 1974, the Paris’s central slaughterhouse, operating since 1867 in La Villette in the outskirts of Paris, officially closed its doors. Its closing was part and parcel of the emerging supra mass-consumption mode of the postmodern period and beyond.1 Massification was changing forever the modes and mores of the global west, including the ways people related to food and its origins, its care, its provision, its delivery, its way of cooking. Small neighborhood butcher and dairy shops, cow included, were fast disappearing from the cities, progressively substituted by supermarket chains, opening the way to corporate ultra-processed and ultra packaged fast-food. Former modernist central markets like Les Halles, the belly of Paris, as Emile Zola put it, or El mercat del Born in Barcelona, my city, were demolished or re-designed converted into multi-function techno-art and thematic parks. Spectacular parks. Mass-culture and the Debordian society of the spectacle had arrived after all, and techno-multimedia parks and sites and buildings embodying the logic of the postmodern urban were being erected left and right by the acclaimed architects of the period. Such as Bernard Tschumi, who in 1980 won the international competition to design and build La Villette’s Park on the 125 acres of the old abattoir.

Tschumi envisioned the whole park as a series of separated but integrated spaces, “follies,” as they were called, and asked Peter Eisenman, who in turn asked Jacques Derrida, to create a garden for one of such “follies.” Yes, Derrida said. But not any garden, a khora garden. The project, however, notoriously failed. A khora park was never built, and the knowledge we have about it comes mainly from the compilation of Eisenman and Derrida’s ideas, drawings, and conversations edited by Thomas Leeser and Jeffrey Kipnis and published in 1997 as Chora L. Works.2 In this presentation, I will not go into the book in depth. Others have done that, and done it well—Francesco Vitale and Geoff Bennington, among others. Here, I simply offer some thoughts on what might be at the core of the failure’s project. A failure I see relating to the non-attention paid to the old modernist abattoir that forms, or should have formed, the substratum of the park.

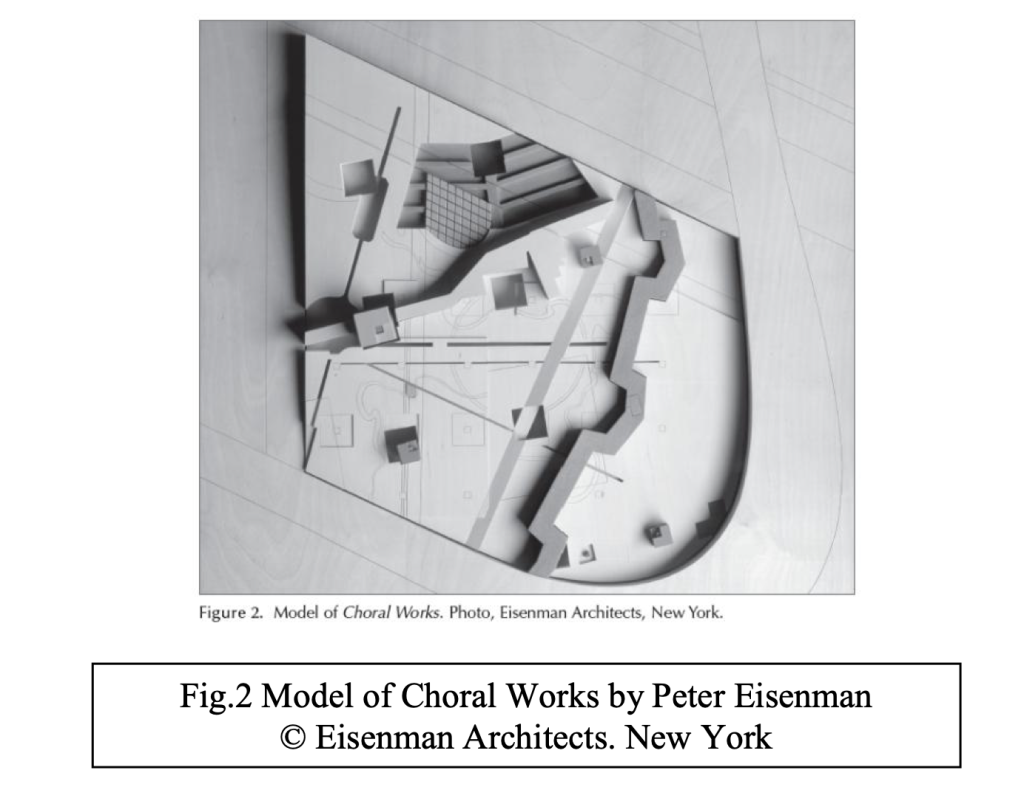

In the late sixties/early seventies, times had certainly already changed. While the modern-industrialist era had already begun to turn away from natural cyclical time to what Guy Debord termed “pseudo-cyclical time,” a time still leaning “on the remains of cyclical time,” the postmodern mood of the sixties, for its part, was fast diving into a “spectacular time” (Débord, Ch. 150). A time set to erase not only all traces and remains left over from cyclical time, but cyclical time itself. Pos-modernism after all worked on the surface, while the remains of time tend to sediment in the substratum. Interested in the thinking of time and space, it makes some sense then that Eisenman and Derrida thought of the possibility of building a park around the theme for the khora garden. Derrida had already started work on khora—a concept, khora, taken, as we know well, from Plato’s Timaeus, with an explicit reference to khora as a substratum. Eisenman on his part, a thinker, in his own words, interested in Heidegger, Nietzsche and also Derrida, embraced the proposition wholeheartedly. They presented the project as “a study of time,” attempting “to replace the actual conditions of time, place, and scale”—at least Eisenman did— “with analogies of these conditions.” Here is the drawing of the project:

And here is the description from Eisenman Architects’ web portal:

This project for a garden in the Parc de la Villette is a study of time – past, present, and future – and a questioning of representation in architecture. It attempts to replace the actual conditions of time, place, and scale with analogies of these conditions. The site, for example, does exist at a certain time – the present – yet the project site is made to contain allusions to the present, past, and future. To this end, analogies are made between the conditions that existed at the site in 1867, when an abattoir occupied it, to Paris in 1848, when the site was covered with the city walls, and to Paris at the time of Bernard Tschumi’s La Villette project – the present. Combined with these traces of time are representations of our Cannaregio project, which coincidentally shares some of the same features as the present site – the wall, the abattoir, and an existing grid. In this way, the site contains its own presence as well as the absence of its own presence (the past and future) in a set of superpositions.

(Eisenman Architects. “La Villette.”)3

With the excitement of the khora project and their focus on time, however, perhaps architect and thinker forgot to pay closer attention to the literal substratum of the Park, which is somewhat surprising. The Cannaregio project Eisenman was referring to is the Town Square he built in Venice in 1978. The first time, he realized, that, “what was wrong with my [previous] architecture was that it wasn’t from the ground, from inside the unconscious, from beneath the surface” (Iman Ansari, “Eisenman’s Evolution”). If for the khora garden, therefore, that “real” connection “from the ground, from the unconscious, from beneath the surface” was so hugely important for both Derrida and Eisenman—it was Derrida who had noticed already in his first draft essay on khora how, for Plato, the concept implied a substratum—, that connection did not register in the project on how to “build” the garden. The project for the khora garden did not make explicit reference to the function and sensorial underground universe that accompanied the butchering of the animals in the old abattoir. Although the ground of La Villette’s slaughterhouse had soaked with the blood and spills of the animals, none of it shows in the Park today, nor it is referenced in Derrida’s and Eisenman’s project. Khora, in Plato’s reference, is not only a substratum, we know. But without the idea of a substratum, no khora was there to be thought—even less to build on and dwell in it, literally or poetically.

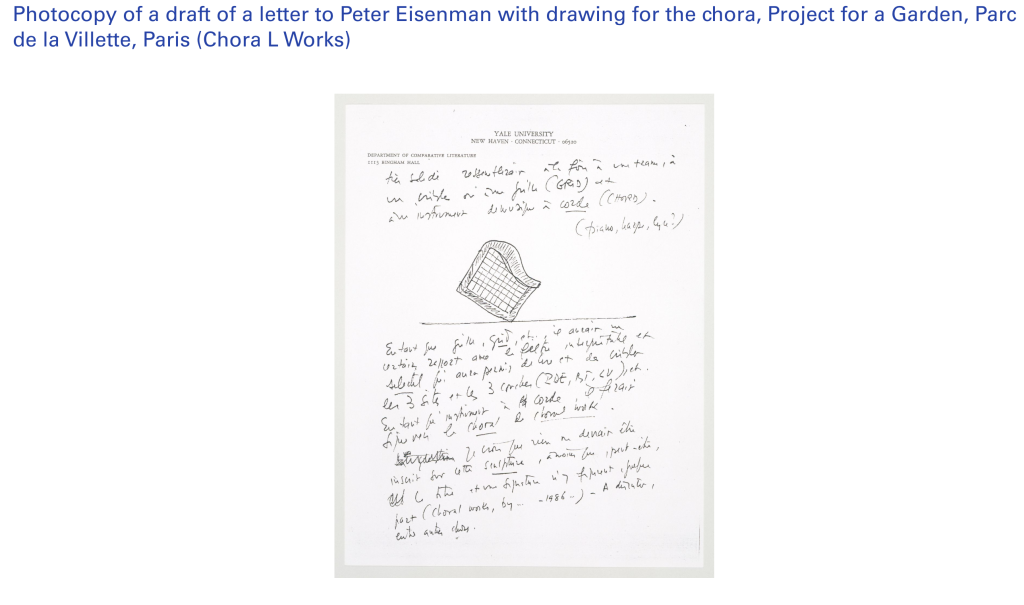

But were the pair really set to build a “real” khora garden, or, were they from the very beginning just playing with architectural ideas? In fact, Eisenman the architect did not seem that interested in seeing the project realized—while paradoxically, Derrida the philosopher was more driven toward the actual building of the garden. Derrida even drew the sort of utensil he thought Plato was referring to—a strange gadget emphasizing the grids and mathematical possibilities for that space/non-space that may be khora. Here is the drawing:

The problem, though, is that Derrida misidentified the kind of utensil Plato was referring to, which was not, I think, the sort of metal grid Derrida drew, but, probably, a real fire fan made of jute. Similar to this one:

In missing Plato’s fire fan, fire itself is missing. Derrida and Eisenman missed the possibility of retrieving the living fire at the heart of khora, in the underground, and with it, the hearth which would perhaps have made the project possible. Eisenman explained in an interview that, for him, a material, real architectonic outcome was not relevant: “The ‘real architecture’ only exists in the drawings. The ‘real building’ exists outside the drawings. The difference here is that “architecture” and “building” are not the same” (Iman Asani). Something akin to what Heidegger wrote in “Building, Dwelling, Thinking,” opening the essay with these words: “[The] thinking about building does not presume to discover architectural ideas, let alone to give rules for building. This venture in thought does not view building as an art or as technique of construction; rather, it traces building back to that domain where everything that is belongs” (347). Was then the khora garden Derrida wanted to build that domain where everything that is belongs? A sort of originary substratum? A sort of originary home following rules of hospitality? If so, only if building would acknowledge that domain that isn’t, that domain of non-space and non-time, embedded within the Heideggerian fourfold and very akin to the concept of Gaia; only if a “khora” garden that, similar to the Borgesian aleph, could absorb the spills of life and death that had reeked from the old abattoir; only if a home or garden could be in synch with the fourfold and nesting within Gaia, only then building could lead, it seems to me, to dwelling—and then, perhaps to thinking. And how would that be possible without acknowledging that the “fire” in a khora garden, its heart and hearth, would necessarily need to retrieve the butchering of animals that formed the ground of La Villette’s park? To care for it?

Derrida noted in his reading of Heidegger’s being and history that dwelling relates to the care of the house and the home,

to dwell is also to have the keep of one’s house and what is stored in it, and to have the keep of this always-already that is the meaning of my relation to the house. Historiality is being in an always-already, is to be unable to go back any earlier than the house, for to be born is to be born in a house, in a place that is arranged and ready before me; it is my originary here, qua here, that I did not choose but on the basis of which every explicit choice will make sense.

(Heidegger: The Question of Being & History, 59)

In the after-effect of the post-industrial Anthropocene, once gone the substratum implicit in the old natural cyclic time; once greatly damaged the skin of the earth and of the world (I am thinking about Jean-Luc Nancy here), are building and dwelling in the sense of care of the home, the hearth, and the fire still possible at all? Is it possible even to light or maintain a fire? What the architect and the philosopher failed to really comprehend when discussing the khora garden project is, I believe, that, despite Tschumi’s claim that the old abattoir was quoted in the design of the park, and Derrida’s and Eisenman’s efforts to also do it—see Chora L Works—the quotations, actual and proposed, were actually performed only on the surface of the site; not from the ground, even less from the unconscious or the literal underground. Because nothing but a black hole, a quantic black hole seems to be under the actual Park. No underground marks able to relate to khora are there anymore. Because, khora, a (non)receptacle, before the arrival of the Anthropocene let itself be a sort of substratum where things and beings could fall into, as well as some sort of “seat” (hedra, 52b1) to simply rest, or “be” (49e7–8, 50c4–5, 52a4–6; Plato, Timaeus, Zeyl and Sattler); a substratum, a pause, a cove, a nest, a cradle; the interval needed to breathe. Khora, which in Timaeus, Derrida tells us, “at times appears to be neither this nor that, at times both this and that” (On the Name 89), fluctuating “between the logic of exclusion and that of participation” (89). A singular, virgin, completely foreign place according to Derrida; a “pre-philosophical, pre-originary non-locatable non-space that existed without existing before the cosmos” in Niall Lucy’s words (Lucy, A Derrida Dictionary 68), khora, it seems, has vanished from us. Like the old gods of nature, who are not in the earth for us anymore. Like the muses, who have abandoned us. “In the current state of the world,” Heidegger said in his well-known 1966 interview with Der Spiegel, “[o]nly a god can save us. The only possibility available to us is that by thinking and poetizing we prepare a readiness for the appearance of a god, or for the absence of a god in [our] decline, insofar as in view of the absent god we are in a state of decline.”4

How then to get to building, dwelling, and thinking when La Villette’s substratum was in 1980 already poetically in-accessible, inexistent? At the time of a raging Anthropocene when the relation existing for millennia between death, animals, and [food] consumption was already for us, humans, almost gone? There was from the start an inherent incompleteness at the core of the project that Derrida and Eisenman did not handle. The new park of La Villette left no trace of the former 125 acres slaughterhouse; and in doing so, any possible left-over links between humans and Gaia or the fourfold, between consumption—in this particular case, food consumption—and death were also gone. The park spectacularly filled the literal hole left behind by the demolition with its many buildings and structures. It left no hint of their former function—no pungent odors, no blood-stained bricks, no desiccated animal parts spilled over, or under, the new park.

Any animal remains that could still be reeking from the slaughterhouse–their pain, odors, viscera, and organs–disappeared into the demolition’s black hole. Yes, the former old abattoirs built in the nineteenth century had already aimed to put distance between death and consumption. Like the one in La Villette, they were built as part and parcel of “the logic of the modernization of urban space” (Denis Hollier, quoted by Brantz, “Recollecting the Slaughterhouse”). Yes, they had come to signify “the extent to which such distantiation [led] to the rationalization of everyday life and to the instrumentalization of death.” (Brantz, “Recollecting the Slaughterhouse”). But, while embodying the industrial logic of modernization of the urban space, their closing of the old slaughterhouses one hundred years later, not only increased the distance “between consumption and death:” they cut out their relation. And with it, the fire that lit the hearth. With an Anthropocene machine, masked as spectacle, already in the sixties and seventies and eighties going at full throttle and riding high on the dragon-force of wild extractive capitalism (Stiegler) the co-habitation between humans and animals, between humans and the rest of biotic and a-biotic systems of the planet was pushed farther away.

I am not poetizing the slaughtering of animals before modernity. I don’t know if any of you have ever been present to a traditional, rural slaughter of a pig, a pre-industrial ritual that has nothing to do with distanciation. I have; many, many years ago when I thought I was a sophisticated urban young woman. The horrible high-pitch screams, shrieks and roars the pig made terrified me. I still hear them. And yet, the slaughter, performed in a Catalan masia, a farmer’s country house, was a celebratory intimate affair where only close friends were invited. It implied, it required, better said, a reckoning with the fact that there was going to be food on the table throughout the year. Every single part of the animal except the eyes, and including the blood, was prepared and preserved to be eaten by the members of the family.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the traditional rural slaughtering of animals was practically extinct, and the already weakened sounds and odors and bloody fluids of the animals being slaughtered in the old modernist slaughterhouses came to a halt. Animals, pigs, cows, and chicken, who had already since the sixties been put in industrial farms, were increasingly given hormones and being genetically treated so they, now converted into monstrous amalgams of flesh, without proper wings, or tails, or tits, or mouths could be compressed, packed, and fed and engrossed non-stop. While it was bad enough that modern industrialization had made modernist “slaughterhouses emblematic of the rise of mass-production and the amalgamation of science, technology, and state politics,” post-industrialization and the increasingly global post-stateization took such amalgamation to new heights. What is seeping into the substratum now is the massive waste of chemically fed and genetically altered matter from chicken, pigs, and other domesticated animals. Removed from the natural cyclical time of death and renewal, they are building up as Anthropocene markers.5 Instead of khora, what we have now in the substratum is fossilized chemically and genetically altered chicken bones.

Heidegger’s “god” has abandoned us. We do not hear the cries and plight of the animals, we don’t smell their odor, we don’t feel their touch nor even their absence; same with plants, etc.; same with the planet itself. Even for Derrida, it took a while to explicitly recognize the animal we are, to let the eyes of a dead elephant, Louis XIV’s, look back at us from the autopsy table (The Beast and the Sovereign). What to do, then? Perhaps, as Derrida himself intended in projecting the khora park, to engage with a poetics of the follie. To take a step back. An infrapolitical step back that would allow us, maybe, just maybe, imagine a khora garden as the follie Hieronymus Bosch painted as “The Garden of Earthly Delights.” A Geodome-khora garden fluidly incorporates all in its bio-sphere. A khora that would allow us a glimpse of the primeval arche-forest, a declining space/non-space where all sorts of life cohabitation and combination are made possible. A Geodome-khora Garden echoing Gaia perhaps?

Notes

- I understand the postmodern period to comprise the years expanding in Europe from the Marshall Plan to the beginning of the twenty-first century. ↩︎

- Chora L. Works. Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman. Thomas Leeser and Jeffrey Kipnis, eds. Monacelli Press, 1997. ↩︎

- Eisenman described the Cannareggio project in an interview with Iman Andari as follows: “I realized that what was wrong with my architecture was that it wasn’t from the ground, from inside the unconscious, beneath the surface. So the first evidence of this occurs in Cannaregio where for the first time I do a project that is totally in the ground. And it’s not only in the ground, it’s also urban. But it’s also not real. It’s conceptual; and uses Corbusier’s unbuilt hospital project as an initial context. This is in 1978. In 1980 I’m invited to Berlin to do the Checkpoint Charlie project, which includes the garden of walls. You can’t walk on the ground of Berlin even though it is a project inscribed in the ground. And then I do the Wexner Center. A number of these projects fall within the concept of artificial excavations. The ground afforded me a critical dialogue with the then current (1978 – 1980) theory of Figure-Ground Architecture: the black and white drawings of Collin Rowe and the contextualists, work done for Roma Interotta using the Nolli map of Rome. What I was doing was the reverse. I was attacking the historicizing obviousness of “figure-ground” and trying to make what I call a “figure-figure urbanism.” And that of course had to do with my interest in Piranesi, and Piranesi’s Campo Marzio – actually we did an exhibition at the Venice biennale last year on the Campo Marzio. So all of these things come together. It’s not all gratuitous or superficial, in a certain way it’s a kind of life work for me. My own psychological work and my own thinking, my teaching, is of a piece. I cannot say that the first period was better or the second period was better; they were different and I was at a different stage in my life. And they have all relevance; they are both in text and in built form. I have both built and written in all three phases of my work. So that’s basically how I get to Cannaregio.” Iman Ansari. “Eisenman’s Evolution: Architecture, Syntax, and New Subjectivity” 23 Sep 2013. ArchDaily. Accessed 25 May 2024. <https://www.archdaily.com/429925/eisenman-s-evolution-architecture-syntax-and-new-subjectivity> ISSN 0719-8884 ↩︎

- Martin Heidegger, “Nur noch ein Gott kann uns retten,” Der Spiegel 30 (Mai, 1976): 193-219. Trans. by W. Richardson as “Only a God Can Save Us” in Heidegger: The Man and the Thinker (1981), ed. T. Sheehan, 45-67. ↩︎

- See: Carrington, Damian, “H-bombs and chicken bones: the race to define the start of the Anthropocene,” The Guardian, 6 Jan 2023.

↩︎

Works Cited

- Ansari, Iman. “Eisenman’s Evolution: Architecture, Syntax, and New Subjectivity”, in Archdaily, (September 23, 2013).

- Brantz, Dorothee. “Recollecting the Slaughterhouse: A History of the Abattoir.” In Cabinet Magazine, Issue 4, 2001.

- Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. New York: Zoonebooks, 1994.

- Derrida, Jacques. Heidegger: The Question of Being & History. Edited by Thomas Dutoit. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2016.

- —. On the Name. Translated by David Wood. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.

- Derrida, Jacques & Eisenman, Peter. Chora L. Works. Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman. Thomas Leeser and Jeffrey Kipnis, eds. New York: Monacelli Press, 1997.

- Eisenman, Peter. “Eisenman Architects.” https://eisenmanarchitects.com/La-Villette-1987.

- Heidegger, Martin. “Building, Dwelling, Thinking.” Basic Writings. Revised and Expanded Edition. Translated by David Farrell Kroll, New York: Harper Collins, 1993.

- —. “Nur noch ein Gott kann uns retten,” Der Spiegel 30 (Mai, 1976): 193-219. Trans. by W. Richardson as “Only a God Can Save Us” in Heidegger: The Man and the Thinker, ed. T. Sheehan,New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1981.

- Lucy, Niall. A Derrida Dictionary. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004.

- Plato. Timaeus. Translated by Donald J. Zeyl, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2000.