James Martell

Lyon College

Volume 16, 2024

Socrates: “Tell me, do you deny altogether the possibility of such a craftsman, or do you admit that in a sense there could be such a creator of all these things, and in another sense not? Or do you not perceive that you yourself would be able to make all these things in a way?” “And in what way, I ask you,” he said. “There is no difficulty,” said I, “but it is something that the craftsman can make everywhere and quickly. You could do it most quickly if you should choose to take a mirror and carry it about everywhere (…)”’

Plato, Republic, 596d

“Le combat théorique, fût-ce contre une forme de violence, est toujours la violence d’une incompréhension.”

Maurice Blanchot, L’écriture du désastre, 122.

Fig. 1. [Francisco de Goya, Duelo a garrotazos (1820-1823). Museo del Prado.]

Abstract: “Am I a fascist?” How does one pose to oneself such a rarely asked, yet essential question?1 In other words, looking into what kind of mirror could one even ask a question that makes our whole being recoil in repulsion? Given its severity and importance, such an essential and devastating self-interrogation would require not a simple mirror or reflective surface, but one that could reflect not only our physical or aesthetic traits, but also the most essential, our ethical and perhaps even our ontological design. Following Nicoletta Isar’s insight, according to which, in Plato “[b]oth the cosmogonic and the bodily chôra seem to have been conceived after the same paradigm of a specular ground able to host the reflection of the image” (45), I would venture that the only reflective surface adequate to such a self-interrogation is a khôra, or what I would like to call a khôratic mirror.

Thus, trying to pose this, perhaps, unanswerable question, or to ask it in a more theoretical tenor (“is the unsplit ‘I’ necessarily a fascist position?”), this essay is a reading of, or rather an attempt to reflect ourselves on khôra2 as a surface that (in the undecidability of its translations between a thing [receptacle, place, territory, and mirror] and a living being [mother or wet-nurse]), like the female figures or “queens” that Michael Naas highlights in his reading of Derrida’s “Faith and Knowledge,” Miracle and the Machine [Gradiva, Persephone, and Esmeralda Lopez] “beckons to us and calls to be put on the scene (274).3 It is this beckoning or call of4 khôra as the rising of the reflective surface of the ground, and the possible relations of this rising to the stupidity and malevolence where—according to Deleuze in Difference and Repetition—fascism breeds, that this essay investigates.

Thus, trying to pose this, perhaps, unanswerable question, or to ask it in a more theoretical tenor (“is the unsplit ‘I’ necessarily a fascist position?”), this essay is a reading of, or rather an attempt to reflect ourselves on khôra2 as a surface that (in the undecidability of its translations between a thing [receptacle, place, territory, and mirror] and a living being [mother or wet-nurse]), like the female figures or “queens” that Michael Naas highlights in his reading of Derrida’s “Faith and Knowledge,” Miracle and the Machine [Gradiva, Persephone, and Esmeralda Lopez] “beckons to us and calls to be put on the scene (274).3 It is this beckoning or call of4 khôra as the rising of the reflective surface of the ground, and the possible relations of this rising to the stupidity and malevolence where—according to Deleuze in Difference and Repetition—fascism breeds, that this essay investigates.

Keywords: stupidity, Ground, fascism, khôra, Deleuze, Derrida, modernism, surfaces, Goya, Balthus

1. An Ocean, the Mud, the Stomach Lining.

Since, in our European tradition the notion of Grund as both “ground” and “reason,” together with its derivatives Abgrund, Urgrund, Ungrund, are inextricably linked with khôra,5 and since Grund also means “basis” and “soil,” let us begin by looking at a couple of literal surfaces. We will describe them as “obscene surfaces” attending to this adjective’s double etymology, according to which what is ob-scene or obscenus is what moves on or towards (ob-) either a “scene” or a “caenum,” namely: mud, mire, or shit.6 As we can infer, such obscene surfaces—between a theatrical scene and excrement—are where some politicians commonly stand: on a theatre or stage, or in the mud, the mire, the muck of the hateful and fascist drives they elevate in order to gain or preserve power. As a consequence, through their spectacular, scenographic and excremental obscenities, these obscene surfaces are able to give us an insight into what we term “fascism,” fascistic actions and spaces, and, perhaps, if there is still room for hope, at the end they might give us a hint as to how to get out of such mires, even if just for a moment.

Given the growing, insidious and obscene fascist environments we are currently living in, not only in the USA this year (2024) with the threat of a return of Trump to power but also in Argentina, Hungary, Russia, Italy, Iran, China, Israel, and so on, let us approach these surfaces carefully, since fascism seems to spring easily around all corners, especially when and where we, in our identities, feel safest.7 Let us do it through two distinct scenes, one from a painting, and the other one from a letter. The painting is Duelo a garrotazos (Duel with Cudgels) (1820-23), one of Francisco de Goya’s so-called Black Paintings, described in a poignant ekphrasis by Michel Serres in Le contrat naturel, his 1990 book revisiting Rousseau’s Le contrat social and proposing a post-human expansion of the social contract, adequate to our era of the anthropocene and climate catastrophes:

A pair of enemies brandishing sticks is fighting in the midst of a patch of quicksand. Attentive to the other’s tactics, each answers blow for blow, counterattacking and dodging. Outside the painting’s frame, we spectators observe the symmetry of their gestures over time: what a magnificent spectacle—and how banal! The painter, Goya, has plunged the duelists knee-deep in the mud (la boue). With every move they make, a slimy hole swallows them up, so that they are gradually burying themselves together. How quickly depends on how aggressive they are: the more heated the struggle, the more violent their movements become and the faster they sink in. The belligerents don’t notice the abyss (l’abîme) they’re rushing into; from outside, however, we see it clearly.

(1; FR 13)8

Serres continues by describing the common reaction in front of the painting, the question: “Who will die? we ask. Who will win?” (1; FR 13). Then he explains the real stakes of the wager. Contrary to what we believe, these are not two positions, two combatants. There is a third, and most important element: “the marsh (marécage) into which the struggle is sinking” (1; FR 14). If this is the most important position, element, and place, it is because “it is more than likely that the earth will swallow up the fighters before they and the gamblers have had a chance to settle accounts” (1; FR 14). In other words, inside this marsh, this mud, this earth, there will be no more two combatants, neither two gamblers, nor two of anything, even if they resemble each other so much as to be one engaging in an autoimmune battle. In this swallowing marsh, there will be no more division nor sharing (partage), no more partition, no more accounts, just swallowed and dead indistinction. What is more, contrary to Serres’ hope, if the belligerents don’t notice the abyss, neither do we nor everybody else does, since to this swallowing marsh, the sinking earth, there is no outside, no transcendent place from where to see it or think it clearly.9

Commenting on this lack of “outside” or “transcendental place” from where to critique in Goya’s oeuvre,, in his analysis of the Caprichos Anthony J Cascardi underlines what he calls “the ‘bottomless’ nature of [the] critique” as a significant and idiomatic trait of Goya’s art:

As soon as the conventional pathos and sentimentality that appear at the surface level of this caption crack, we are exposed to a potentially bottomless critique of the social world and in particular of those social relations that are driven by love and desire among women and men. / The “bottomless” nature of that critique is significant. Many of the Caprichos are images that refuse to offer any internal position from which to represent the truth of things in a coherent and consistent fashion, especially in the social world.

(159-62)

Such “bottomlessness” as a constant figure in Cascardi’s study of Goya underscores not only the repeated marshes, mud- or excrement-like spaces in Goya’s work—as well as his floating, “groundless” characters—, but also their connection to the types of violence and self-delusion that we can associate not only with pre-totalitarianism but also with proto-fascist, fascist and neo-fascist political forms in the 19th, 20th, and first quarter of the 21st centuries. Precisely because in the germinating ground of proto-fascistic violence all distinctions, partitions, and accounts dissolve, bringing on what Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback has recently called “the fascism of ambiguity” (xi),10 such Goyan marshes or muddy surfaces recall Plato’s khôra, since in its thinking, we are also not exempt of its effects, and are only able to perceive it through a “bastard reasoning” (λογισμῷ τινι νόθῳ [52b]).

Here is the second obscene surface, contained in a letter written by Derrida to his friend Lucien Bianco during the May 1958 crisis of the Algerian war of independence, while he was doing his military service in Koléa, Algeria. He writes: “Fascism will not pass (…) never had my faith and my fear as a democrat seemed so very ‘bloated’ (entripaillées) and the fascist danger so close, so concrete, so pressing” (97; FR 126, translation modified). Derrida continues, describing the confusing liquid surface to Bianco—and us: “I’m at a complete loss, can’t grasp anything (ne mordant à rien), a second-class soldier lost in an ocean of malevolent stupidity (connerie malfaisante) (…)” (98; FR 127). As we can see, the abject, visceral, and organic tenor of the metaphors he uses—“entripaillées,” “ne mordant à rien” and “l’océan de la connerie malfaisante”—portray not only his affect, but also a view as to what constitutes for him fascism and the malevolence and stupidity that provoke and sustain it. Through these metaphors, the tripes and the ocean11 signify not only the bodily reaction as well as the personal sensation of drowning, but also something essential about stupidity and malevolence in general: their abject force of undifferentiation—through consumption, drowning or swallowing—as well as their ubiquity as non-solid grounds (or non-solid reasons as Gründe) where everything can sink and be lost in muddled indistinction. Interestingly enough, such tripes and ocean find a connection in Deleuze’s own brief and never published reflections on khôra during his 1987 seminar on “Leibniz and the Baroque,” when he describes the Platonic notion as a “living membrane,” or a “stomach lining” where “everything has or takes place (tout a un lieu), in other words, as the mark of a necessary yet vanishing omnipresent topos.”12

Like Serres’ and Goya’s ground, mud, and marsh, Derrida’s “ocean of malevolent stupidity” threatens to swallow all participants, distinctions, and differences, including his own philosophical and personal capacity to discern or to “bite” (mordant) what is happening at this point in time during the Algerian war (1954-1962). This threatening lack of distinction is a banal spectacle (“how banal!” says Serres of the duel in Duelo a garrotazos [1; FR 13]), a scene of everyday life (observable in Goya’s Spain in the early 19th century, in the middle of the conflict between liberales and absolutistas or in the confused bodies of his painting May 02 1808 or The Charge of the Mamelukes [1814], where the distinction not only between French soldiers and Mamelukes and the Spanish citizens but also between the hatred against the “foreigner” gets lost between the native Spaniards, the native French, and the Mamelukes [called “moors” by the Spaniards] coming from the Middle East; just as it is observable in France and Algeria after the threat of fascism and Nazism was, supposedly, squashed, with the end of WWII) or of the banality of the everyday (what Heidegger called das Man), the stupidity of our modern time or of our time as the quintessential stupid epoch, the one constantly threatened by fascism(s) as democracy’s autoimmune disease.13 Now, if such a lack of distinction is distinctively modern, it is so in the sense of modernity analysed by Eric Santner in The Royal Remains, as an epoch determined by the remains of the monarch’s bodily excess and the effects of the essential inadequacy of this excess upon the democratic body. In other words, modernity begins properly with the excess of the king’s divine and transcendent sovereignty spilling into the purely immanent demos or democratic body. Such a definition begs the question: what happens when sovereignty never splits completely from the king’s body, as in Goya’s—and even in our contemporary—Spain. Perchance what takes place is the radical modernity—in the sense of essential but also of so original that it might have not been completely born yet, like a Beckettian character—of Goya’s Caprichos, Disasters of Wars, and especially, of the Black Paintings, to which we turn, close to the end, or at least to one of them, the Semisunken Dog.

As we will see when we consider below the configuration of what Didi-Huberman calls the “pan” in paintings, it is no coincidence that Santner’s best illustration of the king’s bodily excess is—similar to Goya’s marshes or indistinct grounds—an un- or under-differentiated khôratic space within a mimetic painting, in this case, the empty space above Jean-Paul Marat’s corpse in Jacques-Louis David’s La mort de Marat. For Santner, it is such an empty space or “pan” that embodies the transcendent bodily excess of—what Kantorowicz called—the King’s two bodies, at the moment (1793, the beginning of the Terror after the French Revolution) when such an excess, needing a new body to take place, that is to say, a new representative or representation, finds no appropriate or sufficient one in the demos or people.14 This is, in Santner’s reading of David’s painting (supported by T. J. Clark’s reading of the same painting in Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism), an inaugural moment of modernism qua political modernity, the moment of the transition from a clear and delimited representation of divine and transcendent sovereignty, to the purely immanent sovereignty of the demos. If such a political transition opens up the ground for modernist art, it is because the spectral dimension of the King’s two bodies, its “flesh” (“the sublime substance that the various rituals, legal and theological doctrines, and literary and social fantasies surrounding the monarch’s singular physiology [the arcana that fill the pages of Kantorowicz’s now-canonical study] originally attempted to shape and manage” [Santner, ix-x]), cannot be completely represented, nor contained in a purely and clearly delimited mimetic figure. In Santner’s words:

What makes modernism modernism is that its basic materials are compelled to engage with and, as it were, model the dimension of the flesh that is exacerbated to an unbearable degree by the representational deadlock situated at the transition from royal to popular sovereignty. What, in historical experience, can no longer be elevated, sublimated, by way of codified practices of picture-making to the dignity of moral allegory, introduced into a realm of institutionally—and, ultimately, transcendentally—authorized meanings, now achieves its “sublimity” in a purely immanent fashion, that is, in the various ways in which the vicissitudes of this abstract yet inflamed materiality itself becomes the subject matter of the arts.

(95)

Thus, as the indecision inherent to the prefix sub– in the word “sublime” suggests,15 the sublimity of the modern experience entails a hesitation between an elevation and a sinking or falling—another figure of the inadequacy of the lofty excess of the divine king overflowing the body of the populus.16 This dizzying sublime hesitation recalls what Deleuze called in Difference and Repetition the “rising of the ground,” in the sense of a simultaneous and undecidable elevation of the low(est) and/or fall of the high(est), or what the French, including Derrida commenting on his “sublime,” express with the expression “dessus dessous” (above below) This undecidable positional movement is analogous to the necessary aporetic (dis)apparition of a pre-genetic ground as khôra (or a subjectile) in order for anything else—any event, beginning, or distinction—to take its place. In what follows, such an undecidable movement will give us a chance to consider stupidity, topologically, as a transcendental problem. In other words, we will look at the space “where the Sabbath of stupidity (bêtise) and malevolence takes place” (152; FR 198, translation modified), the same Sabbath that continues to draw us at the end of the first quarter of the 21st century into multiple fascisms and their practices.

Fig. 2. [Jacques-Louis David. La mort de Marat (1793). Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium.]

2. The Ground.

It was precisely such an insight on stupidity as a transcendental problem of our modern epoch—like the one personified in the self-destructive (or auto-immune) battle inside Goya’s painting and figured through Derrida’s intestinal and oceanic metaphors for fascism and its effects—that made Deleuze describe it in Difference and Repetition as a rising of the ground without the ability to give it form:

Stupidity is neither the ground nor the individual, but rather this relation in which individuation brings the ground to the surface without being able to give it form (this ground rises through the I, penetrating deeply into the possibility of thought and constituting the unrecognised in every recognition). All determinations become cruel and bad when they are grasped only by a thought which invents and contemplates them, flayed and separated from their living form, adrift upon this dismal ground. Everything becomes violence on this passive ground. Everything becomes attack on this digestive ground. Here the Sabbath of stupidity and malevolence takes place.

(152; FR 197-8, translation modified)

As we know, Deleuze derived the idea of this rising ground mostly from Gilbert Simondon’s theory of individuation, but also from Schelling’s notions of the original ground (Urgrund) and the groundless ground (Ungrund).17 This double philosophical genealogy, together with its complications within each of these philosophers’ oeuvres, marks this notion of the ground between Deleuze, Simondon, and Schelling—together with the individuations and distinctions that it allows, and the perversions and deviations of these processes—as a simultaneously under- and overdetermined notion of an insistent, ineffaceable origin, akin to Plato’s and Derrida’s khôra.18 In Simondon’s work, the ground where forms appear and individuation takes place gets assimilated to Nature, the ἄπειρον (apeiron), the pre-individual, or a pre-individual reality. What is more, because this pre-individual potentiality accompanies individuation continuously in its development from physico-chemical individuation, through vital, psychical, trans-individual, up to collective individuation, Simondon’s ground is also the ground of, and between all of these dimensions. In other words, as their ground, beginning, or surface of appearance, it is the principle of indetermination and play that links and unlinks them continuously in an essential way—namely, not accidentally but as part of their interconnected nature. As a consequence, it is also what constantly threatens to dissolve them in their transformations. Hence, it is both their origins and the place of their principle of autoimmunity, or autoimmune principle—we could say, paraphrasing Derrida’s Freud.

The ground in Schelling behaves in a similar way to Simondon’s. It is ubiquitous and a condition of both emergence (grounding or begründen) and dissolution (ungrounding), an always-there instance allowing the emergence of forms, while simultaneously threatening them with dissolution in its abyss (Abgrund). At the same time, it is, like the ground in Simondon and khôra itself, an over- and under-determined notion, since it avoids, like khôra (or the Artaudian-Derridean subjectile)19 any proper specificity or determination, as well as any common name or genus.20 As Joan Steigewarld explains:

In various works Schelling insistently introduces the ground that is meant to ground as dependent on prior grounding; the ground that grounds is always already grounded. Grounding is thus always absent, never present. And yet grounding is also always at work in nature, as the basis of the endless diversity and life of the world.

(196)

Like Simondon’s ground, one of the main traits of the ground and its grounding in Schelling is that it is a space shared by both a philosophy of nature and an epistemology. In other words, what it grounds and allows to appear are both beings in the world (both organic and inorganic, “alive,” not alive, and in between) as well as our understanding and perception of them. Therefore, it is both an ontological and an epistemological surface or screen of appearance or emergence. Consequently, what it ungrounds when—as stupidity and malevolence according to Deleuze—it rises without letting things take form, can be individual things or forms, or individual thoughts or notions, or even everything at the same time, namely: the possibility of any knowledge as well as of any world. In this sense, the ground is conceived by Simondon and Schelling in an analoguous way as the notion of “schema” was in ancient times, when it had connotations as diverse as “rhetorical (Plato, Aristotle), moral (Plato), geometrical (Plato), logical (Aristotle), ontological (Leucippus, Democritus, Theophrastus, Aristotle), epistemological (Proclus), and physical (Philo of Alexandria)” (Scaglia 24). The difference between the two philosophical notions is that, while the notion and term “schema” became mostly an epistemological and perceptive problem after Kant, the “ground” continues, in all its forms and translations among languages (fond, Grund, background, reason, foundation, but also abyss, depths, bottom, grave, dissolution, etc.) to straddle, confuse, found and determine an infinite variety of spheres of existence beyond the pure episteme.

The chapter of Difference and Repetition where Deleuze speaks of stupidity and malevolence as the rising ground is called “L’Image de la pensée” (The Image of Thought). This chapter begins by describing the question of grounding as the problem of the beginning of thought, both scientific and philosophical. The “Image of thought” described here is precisely the set of subjective and objective presuppositions that sustain the orthodox, traditional philosophical thought that, in Deleuze’s analysis, hinders any possibility of real thought as an encounter. When the problem of stupidity and malevolence appears, it is not a question of finding another image of thought to understand these phenomena (given that the traditional image of thought ascribes them to error), but rather to recognize that they are truly a transcendental problem, namely, a problem of individuation. In other words, they are a problem before the appearance of any image of thought, which are always built on prior epistemological and ontological individuations. This is why Simondon’s theory of individuation is particularly helpful to Deleuze, since Simondon’s objective is to examine how individuation happens at its origin, and not to deduce individuation based on already given individuals. Nevertheless, like the repetitive beginning included in the ontologically sounding title of Beckett’s novel Comment c’est or How It Is with its French phonetic double, “commencer” (to begin), this origin of ontological and epistemological individuation keeps repeating itself in the appearance of more individuations—in Simondon’s view—through the pre-individual element (call it ἄπειρον, nature, or néoténie)21 inherent to all individuals.

If stupidity and malevolence describe, thus, in Difference and Repetition, the moment when the ground rises without form or individuation, and this ground as pre-individual reality is ultimately what allows the origin of individuals, what exactly is the relation between stupidity, malevolence, and the beginning or origin?22 In other words, if—according to Deleuze, Simondon, and, in some way, Schelling23—individuation as a process occurs before the specification of an I or a Me (Je or Moi), what is the connection between the un-individualized/un-formed raised ground as the origin of stupidity and malevolence, and the pre-individualized, pre-formed ground as condition of individuation, and consequently, as pre-condition of specification and personification? In other words, what exactly is the rapport between the pre- and the un- of pre/un-differentiation and pre/un-individuation, or in Schellingian terms between the Ur– and the Un– of the Ur/Ungrund? And, finally, what is our true main question—in these times when the grounds of post-Cold War democracy seem to be turning into the mire of its autoimmune disease, fascism—: if there is an essential link between the ground that rises as stupidity and malevolence, and the ground as place of emergence of all individuation, is there any possibility of intervention or action that can move us from the undifferentiated and ambiguous raising ground of stupidity to a new, different beginning, and perhaps even to new and different forms of individuation? In more urgent words, is there any action that can hinder, stop, or at least suspend the stupidity and malevolence that breed fascism, and instead bring about—at least for a while—a new form of post- or anti-fascist individuation or individualization? Would such a possible intervention or action necessarily pass by a suspension of sovereignty as identity (national, personal, ethnic, sexual, etc.), a suspension brought about through a new re-immersion in the un-/pre-differentiated ground, a re-immersion of our identities into a blurry khôratic mirror that would give us back a kind of “foiled reflection”?

3. Encountering the pan.

When Deleuze invokes the possibility of such a move beyond the rising of the ground, he brings up Bouvard and Pécuchet, Flaubert’s idiot philosophers from his last and unfinished novel. But before this possible beyond opens up, another stage is necessary for Deleuze. Immediately after describing the rising of the ground and its consequences, still within the same chapter, Deleuze considers another genesis: the origin of melancholy. The most important point of this new beginning, for us, is that Deleuze presents it as a folding, a reflected sight on a surface: “Perhaps this is the origin of that melancholy which weighs upon the most beautiful human figures: the presentiment of a hideousness proper to the human face, of a rising tide of stupidity, a deformity in evil, or a reflexion in folly” (152; FR 198, translation modified, my italics). This reflected sight, however, does not appear as a clear reflection in the sense of an identification. Instead, it behaves like the sight of the “pan”24 in paintings described by Georges Didi-Huberman in Devant l’image (translated as Confronting Images). In the pan, it is not a detail (or a group of details) one looks at, but a sight that—like “real thought” as Deleuze describes it in Difference and Repetition—comes to the eye only as an encounter: “One looks for a detail in order to find it; whereas one comes upon a pan by surprise, through an encounter. (…) The pan, by contrast, leaps into the eyes (…) but it still does not permit of identification or enclosure; once discovered, it remains problematic” (268, FR 315; translation modified, Didi-Huberman’s italics, my bolds). One of the main examples of such a pan in Didi-Huberman’s Devant l’image, coming as an encounter to us through a detail, is the red hat in Vermeer’s Girl with a Red Hat, whose “pictorial intensity thus tends to undermine its mimetic coherence; then it ‘resembles’ not a hat, exactly, but rather something like an immense lip, or perhaps a wing, or more simply a colored flood covering several square inches of canvas oriented vertically, before us” (259, FR 305).

Like the ground, which rises unsummoned—in fact, like khôra, it is rather it that summons us—, the pan’s appearance is like an encounter. Its sight is also like the ground because, contrary to the detail, it does not present us with any given form or definite individuation. It does not face us with any clear figure, but rather with the ἄπειρον or pre-individual reality, with what Didi-Huberman calls figurability itself:25 “the pan reveals only figurability itself, in other words, a process, a power, a not-yet (the Latin for this is præsens), an uncertainty, a ‘quasi’-existence of the figure” (269; FR 316). Further, Didi-Huberman adds—underlining the preparatory, pre-forming character of figurability and the pan, and linking it to its un-making, de-forming, or dis-figuring character, or, in Schellingian terms, highlighting the identification between the Urgrund and the Ungrund, between the space of forming and the one of un-forming–: “Now it is precisely because it shows figurability at work—in other words, incomplete: the figure figuring, even, we might say, the ‘pre-figure’—that a pan disturbs the picture, like a relative disfiguration; such is the paradoxical nature of the potential figure (figure en puissance)” (269; FR 316).

Fig. 3. [Jan Vermeer. Girl with a Red Hat (1665-67). National Gallery of Art.]

Following Deleuze, in order to have a chance to extricate ourselves from the ground where malevolence and stupidity emerge, an ulterior movement is necessary after the encounter with the pan, that is to say, with figurability or the pre-individualized reality itself. This is the aforementioned movement of reflection: our reflection in folly/madness. Like any successful movement of reflection as folding, this movement requires a re-cognition. However, this is a recognition of what is precisely un-recognizable because it is not only un-individualized but ultimately un-individualizable, utterly unable to receive form, as the ground or ἄπειρον. Consequently, this recognition in (and of [through a “bastard reasoning” or “dream”]) the ground of folly/madness cannot be a rational or begründet recognition as it is understood by the orthodox image of thought. That is to say, it cannot be a recognition based on the presupposed good will and affinity between thought and the self, a recognition that includes an already formed good image of the reflected self before the real reflection takes place (e.g., I pre-recognize my image as non-fascistic, democratic, essentially good, etc.).

It is precisely this moral presupposition of the affinity between thought and the self that, according to Deleuze, has hindered philosophy from being able to think stupidity as a transcendental problem. Deleuze suggests that it is because literature does not always share this moral presupposition of the goodness and sympathy of thought and the self, that “the best [literature] (Flaubert, Baudelaire, Bloy) was haunted by the problem of stupidity. By giving this problem all its cosmic, encyclopaedic and gnoseological dimensions, such literature was able to carry it as far as the entrance to philosophy itself” (Difference and Repetition, 151; FR 196-7). In other words, it is not in spite of, but because of their idiotic and—we might add—idiomatic literary dimensions that the Flaubertian philosophers, Bouvard and Pécuchet, can finally approach the unrecognizable ground and develop a “pitiful faculty” that allows them to see and recognize stupidity in and as themselves and to not tolerate it anymore. Further, Deleuze continues, it is this literary idiocy that ultimately allows for the “pitiful faculty” to turn into a “royal faculty” “when it animates philosophy as a philosophy of the spirit, in other words, when it leads all the other faculties to the transcendent exercise which renders possible a violent reconciliation between the individual, the ground and thought” (152; FR 198, translation modified). According to Deleuze, this violent reconciliation means that the individual factors of individuation become objects of themselves, constituting thus the highest element of a transcendent sensibility: the sentiendum. Simultaneously, in this reconciliation, the ground itself is brought from faculty to faculty into thinking but always as unthought and unthinking. It is exactly in this way, as unthought and unthinking, that the ground becomes the necessary empirical form under which thinking, within the split I (Bouvard and Pécuchet), can finally think the cogitandum, “in other words, the transcendent element which can only be thought” (153; FR 198). As we can see, even in the space of this violent reconciliation, where thought will be able to think that-which-cannot-be-but-thought or “the fact that we are not thinking yet” (Difference and Repetition, 153; FR 198), there remains the need for a split, the fold necessary for any reflection of thought as stupidity in madness to take place. Therefore, if we want to, in this time out of joint, like Hamlet, absent ourselves from stupidity a while and join him in an essential reflection of our origins and identities—including those that might be fascistic—as a Narcissus we must first recognize the utter alterity of our unrecognizable follies, or of our own Echoes.

4. From Inter- to Trans-individual.

If, in this move from the ground of stupidity and malevolence to the madness that will make stupidity intolerable, according to Deleuze, there needs to be a recognition of the unrecognizable, how do we know that what is being recognized is not already figured, i.e., recognizable? How do we know that what one recognizes is not the detail, form or individual presupposed already by the image of thought’s belief in the inherent goodness and harmony of thought and the self? Or—in terms of our (re)nascent contemporary awareness of the dangers of our own neofascisms rising at the centre of our democratic ideals—: how do we know that our purported recognition of fascist dangers and tendencies is not a detail, a delimited form keeping the recognition of our own fascist stupidity and malevolence safe and unseen, disguised as civic duty, obedience, and good conscience? How do we know that we are not, while trying to escape fascism, engaging in our own micro-fascisms?

Since Deleuze’s exposition of stupidity and malevolence as the rising of the ground is based partly on Simondon’s theory of individuation, it is worthwhile to remember Bernard Stiegler’s analysis of the question. In États de choc, he elaborates on the notion of stupidity in Deleuze and Simondon, explaining it in terms of a degradation of what—following Simondon, he terms—the transindividual into the interindividual. While the transindividual in Simondon’s theory is the intermediary stage between different individuations that move from the physico-chemical, the organic, through the psychical, up to the collective, the interindividual does not allow for new individuations or expansions. It “is an exchange between individuated realities that remain at their same level of individuation, and that search in the other individuals an image of their own existence, parallel to this existence itself” (Simondon 167, my translation, my italics). In terms of Didi-Huberman, what one recognizes thus within the interindividual are the image’s details, not the surprising pan, the figure, not the figure-less figurability. Or in Deleuze’s terms, we could say that the object of the recognition is the I, not the pre-individualized potentiality of expansion within the split I, or the clear thought, not the unthinking/unthought element that cannot be but thought—“the fact that we do not think yet.” In other words, through interindividuality one remains within a traditional image of thought, recognizing only the recognizable, reaffirming the already affirmed identities of the individual (organism, self, nation, cultural identity, cliché, etc.), reinvesting thus its narcissistic image of self.

But how do we avoid the completely formed recognition in the reflection? How do we effect a real recognition in and as the encounter with the ground of folly/madness, a recognition in folly inside the unrecognizable ground as the paradoxical condition of possibility of any recognition, that is to say, in the genetic surface or (back)ground of all formations and individuations—ontological and epistemological—or within the ultimate unfathomable mirror that Plato called khôra? Such a recognition in the unrecognizable is vital for us if, as Deleuze explained, it is from such a rising of the ground as the space of pre- and un-individuation that stupidity and malevolence, and especially the one we have come to known as fascism, can take place. But because it is precisely a recognition of what it is essentially impossible to recognize, of what comes before any cognition that could turn back on itself as re-cognition, arriving to or rather approaching such a recognition is not only an ugly process, given the de-formity and deforming dimension of the pre-forming ground. It is also necessarily maddening, since its place is previous to the image of thought according to which there is a natural affinity between thought and the self, in other words, a rational, moral image of thought and the thinking-self. Thus, such a real recognition must necessarily be a mad (as grundlos, groundless, baseless, or unfounded) re-cognition of what precedes thought—or “the fact that we do not think yet.”

5. Foiled Reflections: “As Alike in Appearance as Possible.”

Let us look at a couple of examples of what such a recognition, in its most dramatic form, might be. As Deleuze realized, our literatures are full of attempts at such a recognition of the unrecognizable, i.e., of the ground upon which any cognition and any individuation will become possible. Samuel Beckett, one of Deleuze’s (and Derrida’s, Cixous’, Blanchot’s, and Adorno’s) favourite writers, made a central part of his literature the instances where such a mad recognition might take place. Such an attempt at this recognition can happen, in Beckett’s work, as a substitution, namely, as the recognition that one is, can be, or can take the place of the other. We see it, for example, in the first words of Molloy, with the substitution of the hero for his khôra-like mother: “I am in my mother’s room,” which would have sounded more like “I am in my mother’s womb” in the mouth of the author, given Beckett’s difficulty in pronouncing the “r,”;26 or in the substitution of Molloy himself by Moran in the novel’s second part. Further, the recognition of the unrecognizable in Beckett’s work can also take place in the double(d) figure of the multifarious inseparable Beckettian pairs (the descendancy of Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pécuchet): Mercier and Camier, Vladimir and Estragon, Hamm and Clov, but also Mouth and Auditor in Not-I, or M and V and Mrs. Winter and Amy in Footfalls.27

However, it is in those of Beckett’s texts enacting directly an encounter between two clear doubles that we find the most striking rising of the ground, together with the possibility of such a mad recognition. We see it, thus, in Film, where, after a chase and a series of avoidances, E (the camera) is finally able to perceive O frontally, which immediately inverts the perceived-perceiver relation, revealing to the viewer “E, of whom this very first image (…) It is O’s face (with patch) but with very different expression, impossible to describe, neither severity nor benignity, but rather acute intentness” (The Collected Short Plays, 169). Such an encounter and final recognition ends, necessarily given its fullness (instead of its foiledness), in O’s slowing passing away on the rocking-chair “as the rocking dies down” (169). In Ohio Impromptu, the recognition gets protracted into the total length of the short play, which describes the doubles clearly in the directions “As alike in appearance as possible” (285), and where the doubling itself gets doubled again by the reflection of Reader and Listener on the “he” and the “man” from the story being read—what potentially continues its doubling folds infinitely, given that the “worn volume” of the story is a double itself of the book on the table.

Finally, Krapp’s Last Tape might be Beckett’s most direct attempt to present this recognition of “a rising tide of stupidity, a deformity in evil, or a reflexion in folly” (152; FR 198). Given the intensity of the oceanic surface as metaphor of the rising ground that we saw earlier in Derrida’s letter, it is significant that Krapp’s realization and vision happened “at the end of the jetty, in the howling wind” (60), just as it is important to remark that Beckett’s own realization of what he needed to do in his work (in order to distinguish it from Joyce’s and other writers, namely, in order to avoid the doubling) happened in his mother’s room, which he substituted in his play with the ocean. Such a realization was, for Beckett himself, as James Knowlson expresses it, “the recognition of his own stupidity” (319), or in Beckett’s words, of his “own folly” (319). The space, location, or topology of these recognitions is, thus, not indifferent. Beckett insisted to Knowlson on the distinction of the location when discussing his and his character’s parallel visions: “Krapp’s vision was on the pier at Dún Laoghaire; mine was in my mother’s room. Make that clear once and for all” (Knowlson, 319). Yet, as we know, due to Beckett’s speech impediment, Knowlson might have heard “my mother’s womb,” which makes the substitution of the womb for the other obscene surface, the ocean, easier—at least within our traditions, which continue to link their cosmogonies to the ocean’s deep (תְהוֹם / Tehom) and to the sacrificed body of a maternal goddess (Tiamat or Thaláttē), and to figure their writing or speaking spirit or space (וְרוּחַ) hovering upon this doubly obscene cosmogonic surface, like a pen upon the page, thusly: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. / And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep (תְהוֹם). And the Spirit (וְרוּחַ) of God moved upon the face of the waters” (Genesis, 1:1-2).28

For now, let us finish our examples of foiled reflections with Dostoyevsky. But first, let us ask: if literature is indeed the optimal space for this recognition, for an attempt to recognize the unrecognizable as the ground of all (re)cognition, how does one go or attempt such a recognition outside of literature? In other words—and since our main object is the particular malevolence and stupidity that we call “fascistic”—how do we recognize what is unrecognizable in the stupid horror and malevolence of everyday, the “real” fascisms of our ongoing epoch? How do we recognize such horrors, especially these days, when we see them hourly, sometimes minute by minute, numbing us, up to the point where, at times, we begin to become immune to them? Or, if ultimately, we cannot recognize such horrors—they are, after all, as horrors, the unfigurable, the unrecognizable—how do we even know where exactly they are taking place, namely, their topological, ontological, and epistemological limits? How do we know if they are not also within our own homes, and as part of our most intimate economies, inside our home libraries?

“Let us finish with Dostoyevsky” appears to be a message of the Ukrainian writer, Oksana Zabuzhko, in her March April 22 2022 column of The Times Literary Supplement, titled “No Guilty People in the World? Reading Russian Literature After the Bucha Massacre.” In a powerful and precise style, Zabuzhko exposes the West’s incapacity to recognize the unrecognisable of Russia’s continuous massacres in Ukraine since the beginning of the war in March 2022—and before. This incapacity to recognize the horrors and their inherent and appalling stupidity comes, she explains, not only from a desire to understand clearly (to designate them as phenomena we can ultimately comprehend), but also from the presupposition that there is something to be understood in Russia’s actions, or, in other words, from the assumption that Putin’s (but also each violent and criminal soldier’s or even civilian’s) “evil” can ultimately be understood, and thus, explained away. According to Zabuzhko, this is:

(…) a clear, basic need that is common to Western people: to rationalize evil; to try to assume the perspective of the perpetrator, to understand his motives and aims, to take up the scholastic position of “devil’s advocate” (the endless attempts among Cartesian minds to decode “what Putin wants”). All this, in the end, implies reaching an understanding with evil, entering into dialogue. After all, dialogue is the air that Western culture has breathed for 2,500 years, and to those raised in the open atmosphere of the ancient agora, it is difficult to imagine that next door there also exists an ancient culture in which people only breathe under water and have a banal hatred for those who have lungs instead of gills.

(TLS)

For Zabuzhko, the recognition of this “under water” horror and stupidity is not impossible due to an absolute ideological or even objective blindness. It is not that the West has not had any perception of past Russian horrors, or that its need to “rationalize evil”—or, in Deleuzian, to doggedly believe in the image of thought’s harmony between thought and the self, and thus in the impossibility of an auto-immunity proper to thought, i.e.: of suicidal, fascistic thoughts29—has sheltered it from the perception of such evil and its logic. As a matter of fact, Zabuzhko says, not only we, Westerners, have known for a long time that Russian culture had this capacity for horror and stupidity, but we have also had proof of it—and perhaps also its seeds—for a long time with us, inside our own homes, on our own proud bookshelves. Because, she ends saying, “the road for bombs and tanks has always been paved by books, and we are now first-hand witnesses to how the fate of millions can be decided by our reading choices. It is time to take a long, hard look at our bookshelves” (TLS).

Thus, let us finish with Dostoyevsky, she seems to say, agreeing with a 1985 column by Milan Kundera.30 Let us finish with Dostoyevsky and with “(…) his cult of emotions and complete disdain for rationality” (TLS), because such a cult and disdain could provoke direct reflections outside of literature. But here we must ask Zabuzhko, Kundera, and ourselves, if Dostoyevsky’s books could work as a direct example, and almost as a pedagogical pre-formation of the past and present violence—and the violence to come—does this make his work an exact reflection of the atrocities, the stupidity and horror of Putin’s regime—as well as of the crimes committed by the Red Army during WWII and ever since? In other words, are Dostoyevsky’s characters the direct doubles of Putin, of his generals, his commanders, and foot soldiers, of the corrupt officials, diplomats, as well as of those civilians who, “stupidly,” believe in all of what they see and hear in Russian media?31

As we know, the question of an exact reflection of the same, between literary characters and their doubles in real life, as well as between fictional and real violence, is a literary question from before Dostoyevsky, posited in its modern form for the first time by Cervantes’ Don Quixote. What is more, it is the ultimate question of literature as Aristotle conceived it in The Poetics, the question of mimesis as the essential trait of the human. Nevertheless, the reflection we have been discussing, the “reflexion in folly,” where the unrecognizable, the ground upon which all recognition can take place, is recognized, is not a reflection of identity. It is, like all narratives about doppelgängers and doubles, a “foiled reflection,” an “almost reflection” with the minimal difference necessary to create an un-heimlich effect. As we know, these reflected and reflective double or doppelgänger narratives are multiple, if not infinite in our traditions; and either in literature, through cinema, or even video-games (which are based, precisely, in this narcissistic doubling), they do not, and will not stop proliferating. Nevertheless, as the double characters in Borges’ short story “El otro”’ insinuate, when we think of the double in modern literature, we always go back to Dostoyevsky’s The Double: A Petersburg Poem. But what is particular, original, or idiomatic, about this double?32 Let me, thus, finish with this originary reflection of modernity in Dostoyevsky’s work, examining briefly the exact moment when the ground rises in this novel, and the “Sabbath of stupidity and malevolence” between the two Mr. Goliadkin begins to take place.

In the novel, the actual original instant of recognition between the hero, Mr. Goliadkin, and his doppelgänger, gets protracted through quite a few pages. It is described as a matter of topological distance, since the two reflected individuals meet first during a walk in the streets. Significantly, the full recognition is rehearsed before it finally takes place at the end of the chapter, with the adverb “almost” deferring its full conclusion. As we, as readers, approach this final moment, Goliadkin’s position is described as a “man standing over a frightful precipice, when the earth breaks away under him (…) drawing him into the abyss (…)” (49). However, just before he finally falls into this abyss (or Abgrund) and fully recognizes his reflection (“what is known as his double in all respects” [50] is stated at the end of the chapter), in this frenzied abyss of undifferentiation, where Goliadkin “was unable to think about anything,” an apparently insignificant third element appears out of nowhere: “Some forsaken little dog, all wet and shivering, tagged after Mr. Goliadkin and also ran along sideways next to him, hurriedly, tail and ears drooping, from time to time glancing at him timidly and intelligently” (Dostoyevsky 49). This dog appears in the dark landscape of the novel like the one in Goya’s Black Paintings (a companion on the second floor of the Quinta del Sordo to the two men from Duelo a garrotazos since their creation) looking up, right at the border of the abyss, to who knows whom, warning of who knows what.33 With its face just above the edge or threshold (limen) of the earth, coming out of the “pan” into another “pan,” Goya’s dog is an undecidable, underdetermined detail, a sublime dog underscoring the topological indecision of the word “sublime”: neither definitively above nor under (the sub- of sublimen [“above the threshold”] comes from the Indo-European *upo which gives us the Ancient Greek ὑπό, hypo, “under”).34 Consequently, the painting has perhaps been misnamed by critics as “Semisunken Dog” when it could well be called “Semirising Dog,” or just simply “Sublime Dog,” “The Sublime is a Dog,” or “The Dog is the Sublime.”

In our traditions, through its shape and positions, as well as through its materiality and its significance as the “closest” animal to man (in terms of familiarity, and here the gender is not insignificant), the dog seems to incarnate, as he does in the original scene of recognition of the double in Dostoyevsky’s novel, the “almost” of our identifications and recognitions.35 It appears as the “foil,” that is to say, as that which prevents—or is prevented—from accomplishing a full identification or recognition (e.g.: “my dog, you’re [almost] my son,” “he died [almost] like a dog”), or as in Goya’s painting, as what hinders the merging of two spaces or two “pans” (brown and yellow, the earth and the sky). Or, according to yet another meaning of “foil,” it rises as a superficial leaf or sheet—a subjectile—, allowing for something or somebody else to appear in an always doubled re-presentation,36 potentially confounding both terms, signifier and signified, characters and/or spaces, or as the voice of M in Footfalls says—while incarnating Mrs. Winter, the mother within a story she is telling to V, whom she herself addressed at the beginning of the play as Mother—“revolving it all” (243, my italics). Sometimes it rises, this foiled and foiling dog, like the dog that Molloy runs into with his bike, early on in the novel, an event which he narrates immediately after a reflection and a resolution: “The fact is, it seems, that the most you can hope is to be a little less, in the end, the creature you were in the beginning, and the middle. For I had hardly perfected my plan, in my head, when my bicycle ran over a dog, as subsequently appeared, and fell to the ground (…)” (The Grove Centenary, 28). The description of this event carries an extra violence in the original French version, together with an idiom that highlights this canine encounter—almost as a redoubling of the violence of the two Goliadkins’ encounter with their dog: “Car je n’eus pas plus tôt établi mon plan, dans ma tête, que je rentrai violemment dans un chien, je le sus plus tard, et tombai par terre (…) (50-51, my italics), translated literally as “that I re-entered (crashed) into a dog, I knew it later, and fell to the ground.”

Fig. 4. [Francisco de Goya. El Perro (1819-1823). Museo del Prado.]

Let us go back to Dostoyevsky. Given the confounding traits and strokes brought by the animal in the originary doubling scene of The Double, it seems that for the final recognition between Mr. Goliadkin and his double to actually take place and, thus, for the novel to properly begin (just as the fatal crashing into the dog in Molloy begins this character’s relationship with Lousse, perhaps the main plot in his story), the dog has to disappear. But just before Goliadkin runs into his double for the last time in the chapter (as in the last loop of a sublime downward [or upward] spiral), this time, finally, “in the same direction”—the one that will take them both, together, to their shared house, room, bed, and story—Goliadkin whispers: “Eh, this nasty little dog!” (…) not understanding himself” (49, my italics)—adds the narrator.

6. Coda or Infinite Reflection.

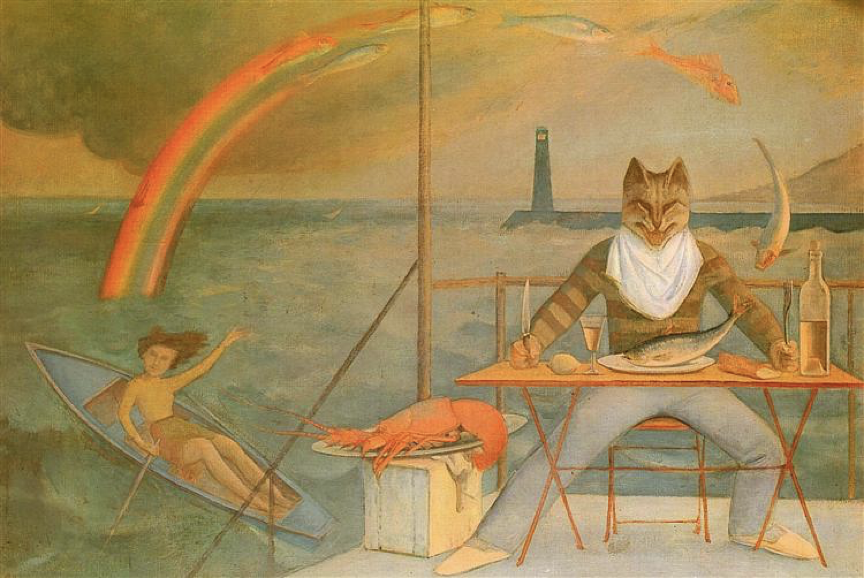

To end, let us look at another scene in our literature almost exactly like the last one. It is also a scene of narcissistic recognition, but this time instead of a dog intruding on the doubling scene, we have a cat. The reflection, here, is also maddening; up to the point where it is not clear if it is a true reflection, or if we have just two doppelgänger or even two + 1. Like Mr. Goliadkin, the subject about to be doubled (or more), does not understand or comprehend himself completely. In other words, it does not grasp where his limits or delineations are, where his individuation begins or ends. The subject is Jacques Derrida himself, and in this obscene scene within L’animal que donc je suis (The Animal That Therefore I am), he is naked in front of a female cat, not anymore like a man and his or a dog, but instead like a Balthusian petite fille or young girl, or like Alice in front of the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland.

What makes this scene of doubling maddening (and since it extends itself throughout the whole book, the reflecting obscene scene constitutes the book itself) is that the subject and object of the event of doubling are unclear, constantly shifting and morphing into other doublings. At the beginning, the first subject that is doubled, reflected upon itself, is neither Derrida nor the cat, but shame itself: “Reflection of shame, mirror of a shame ashamed of itself, a shame that is at the same time specular, unjustifiable, and unavowable” (4; FR 18, trans. modified). This shame of being seen naked by the animal summons later the entrance of, first, a woman, and then of another mirror, what in French is called a psyché, multiplying thus the reflections and the madness of what is reflected: Derrida’s body, Derrida’s sight, the woman’s body, her sight, the cat’s sight, the cat’s body, their doubling on the surface of the mirror, or, even more, their doubling on the maddening reflective surface of the cat’s eyes, the woman’s eyes, the double-cat or double female animal that could be, for Derrida, “in the depth of her eyes, my first mirror” (51; FR 77, trans. modified). Such a reflection of the male author in his object of desire, or in a female subject/object, reminds us, within the European tradition to which Derrida belongs, of the mirror and/or the cats in a Balthus painting, e.g.: Le chat au miroir I or i, or perhaps even Thérèse rêvant, or Nu avec un chat, or even the infamous La chambre, since all the reflections and doublings in these paintings reflect and multiply the women and men, together with their shame, lack thereof, and their desires. As Derrida says in the same scene, here “[w]e no longer know how many we are then, all males (tous) and females of us (toutes)” (58; FR 86). These maddening reflections make Derrida ask thus, not only: “What happens to me each time that I see an animal in a room where there is a mirror (…)?” (58; FR 86-87) but also, and more importantly: “Where do the mirror and the reflective image begin, that is to say, the identification of one’s resembling one (semblable)? (…) Does not the mirror effect also begin wherever a living thing, whatever it be (quel qu’il soit), identifies another living thing of its own species as its neighbor (prochain) or resembling one (semblable)?” (59; FR 88). But how do we delimit this “living thing” (un vivant), “quel qu’il soit” or “whatever or whichever it be,” especially in terms of identification or individuation, and when we are in or on a mirror or reflective surface telling us who we really are, at the bottom, that is to say, within or on khôra? How do we delimit the closeness, if it is a prochain, or the similarity, if it is a semblable (how much does it resemble me? more than a gorilla, than my cat or my dog, or less than my own shadow?)? Or how do we know that it is the same species, since, in the mire of our fascistic times, it seems we cannot even agree to who “fully” belongs to the one human one, or, in the middle of absolute climate catastrophe, we are not sure how to—or even if we should—demark any limits between the sensations and affects among the different genuses in the organic realm? What is more, and what complicates even further all these identifications and individuations, in these complex topologies of “living things” and delimited territories of belonging (nationally, ethnically, linguistically, etc.), are we not constantly both in and on an originary reflective surface, unable to escape the two essential and interconnected dangers: 1) to be doubled by our reflections and 2) to be swallowed in them as in an intestine, a stomach lining, a mire, or the ocean?

If we are still—and forever will be—determined by our traditions, from Dostoyevsky’s doubles, to Goya’s dog, Marat’s death, Vermeer’s red lip-hat, and Balthus’ cats and petites filles, this means that our spirit or spacing (וְרוּחַ), our logos and discourse is still hovering over the surface of the deep and the ocean (the oceanic depth of Tehom and the murdered goddess Tiamat), constantly reflected and reflecting itself, even when it plunges into the depths or the abyss, reaching even those who “only breathe under water and have a banal hatred for those who have lungs instead of gills” (TLS). This eternal relation to an originary reflective surface means that our living space, what Derrida called early in his career, “espacement,” and later, khôra, is completely topological. In other words, in the madness of a reflection in folly, it means that, while individuals and their spaces are delimited and produce reflecting and breaching effects, there is ultimately no unbreachable limit between their interior and their exterior spaces, territories, identities, and individuations. Or as Simondon explains it:

(…) all the content of the interior space is topologically in contact with the content of the exterior space on the limits of the living. In fact, there is no distance in topology. All the mass of living matter in the interior space is actively present for the external world on the limit of the living: all the products of past individuations are present, without distance, and without delay.

(226, my trans)

Therefore, in this lack of distance the reflection is infinite. Or, in other words, there is no more true reflection, as in a Klein bottle. This is the madness or, in other words, the possibility of recognition of the unrecognizable (fact of this) infinite khôratic reflection in (and on) which we all live and die. This is the reflection as the annulment of distance, both spatial and temporal, the surfacing of khôra, nature, or the “pan” (or the dog or cat) and our only chance to recognize “a hideousness proper to the human face (….), a rising tide of stupidity, a deformity in evil, or a reflexion in folly” (152; FR 198, translation modified, my italics). It remains unclear if, recognizing such stupidity and evil as the rising of the ground where we all can reflect ourselves in and on each other, we can also deflect our violent need for recognition and identity and thus suspend our own fascisms, at least for a little while.

Fig. 5. [Balthus, Le chat en Méditerranée (1949), Private Collection.]

Notes

- The exact question “am I a fascist?” elicits, right now (April 11, 2024), 462,000 hits on Google, from the title of a 1934 article on the Jewish Daily Bulletin by W. B. Ziff, through that of a 2008 review of Jonah Goldberg’s book Liberal Fascism on Slate, to questions in Quora like “Am I a fascist if I despise and hate Antifa?” or “I believe in MAGA, but why do my children tell me I’m a fascist? I thought it was good to be antifa” and a subreddit to r/NoStupidQuestions with the same question posed earnestly. There is even a fascist test in another subreddit (to r/CapitalismVSocialism): https://www.idrlabs.com/fascism/test.php (Thankfully, I got “32% Fascist, which makes you Not a Fascist.”) ↩︎

- Besides Derrida’s own texts, Khôra, Sauf le nom, and Foi et savoir, other important texts that treat of khôra are Michael Naas, From Now On and Miracle and the Machine, John Sallis, Chorology, and Mauro Senatore, Germs of Death. Herman Rapaport “Deregionalizing Ontology: Derrida’s Khôra” is particularly insightful in its tracing of khôra’s import from early on in Derrida’s corpus. ↩︎

- The first two figures, Gradiva and Persephone, would inhabit, directly and indirectly, respectively, Derrida’s “Faith and Knowledge.” The third one is an import Naas makes through his extraordinary cross-reading of Derrida’s volume with Don DeLillo’s novel Underworld. ↩︎

- Here the undecidability of the gerund, between the subject and the object would stress the radicality (in the sense of root as ultimate origin as well as of Kant’s notion of “radical evil”) of the un-rationality or Grundlosigkeit (baselessness, groundlessness) of such a rising. ↩︎

- The easiest path to follow such a linkage will pass through German Idealism, particularly through Schelling’s early essay on the Timaeus and in his developments of the Ground (Grund) as Urgrund and Ungrund in the famous Freiheitsschrift. ↩︎

- Antoine Meillet, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine (Paris: Klincksiek, 2001), 456, quoted in https://fr.wiktionary.org/wiki/obscenus#la ↩︎

- An easy recent example would be the optimism that pervaded certain demographics in the USA after Barack Obama’s election in 2008, followed by the certainty that Hillary Clinton would become the next president—setting us up, after the elections of the first African-American president and the first woman, in the path of a more progressive society. But beyond such historical anecdotes, what this essay tries to explore, albeit sometimes indirectly, is the relation between assured identities and fascistic micro or macro drives. ↩︎

- For translated texts, I will give first the English translation pagination and then the original French one signalled by FR, and the original German text by DE. ↩︎

- It is for this reason that I do not believe that the fact that Goya had originally painted the two men not sinking but standing on grass ( https://www.publico.es/culturas/cara-oculta-pinturas-negras.html ) invalidates Serres’ and our contemporary interpretations of it. Even if the “sinking” effect was an accident resulting from the transposition of the painting from the wall to the canvas, it is how such an effect speaks to us concerning our contemporary situation that matters the most as an opportunity to think our time and the modernism that Goya help inaugurate. ↩︎

- It is the paradox of the enactment of the unequivocality of fascism, its frigid and univocal death drive performed nowadays through ambiguity, described by Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback, that this essay attempts to examine through “foiled reflections”: “I found in the world today a new way of imposing the unequivocal meaning of fascism through a dynamic of making every sense ambiguous, when their exacerbation empties them. Fascism as a whole is unequivocal, but today its unequivocality is exercised and imposed through a politics of ambiguation. That is what I have called the fascism of ambiguity” (Cavalcante Schuback, xi). ↩︎

- The fact that the ocean is linked to the French word “connerie,” derived from “con” (cunt), exposes the traditional connections between a swallowing, unstable surface (the ocean or Tehom: the depth), the gaping abyss (chaos), and woman or the female sex (the goddess Tiamat, etymologically related to Tehom). There is thus a “close link between separation and the creation of space, as is suggested in the ancient link between chõrizen (to separate) and chõra (space, place)” (Edward S. Casey, The Fate of Place, n. 37, 351). This link between khôra and chaos is at the centre of this article and of the question of fascism as it ties itself to acts of foundation and beginnings, that is to say, to grounding or begründen (of a nation, a people, an identity, etc.). Maria Sa Cavalcante Schuback explains this fascistic desire “to start again” (after absolute destruction) thusly: “Fascism replaces ‘this must change’ with ‘everything must end.’ This means the replacement of the desire for transformation with a desire for extermination. If transformation implies the desire of the other, fascism wants to replace that desire with the desire of the same once again, always the same, the similar other, which is the desire for the ‘same’ to start again.” (18).

For a consideration of the relationship between ground and the ocean in between Derrida and Heidegger see my “Between the Ocean and the Ground: Giving Surfaces,” Derrida Today, 17.2 (2024), 211-223. ↩︎ - https://deleuze.cla.purdue.edu/lecture/lecture-13-6/ Charles J. Stivale, who transcribed the seminar for the Deleuze seminars, hears an unidentified Greek term at this point of the recording (55:00 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D11eW8G5ZWs&t=3303s). I, however, think Deleuze says ‘paroi d’estomac’ (stomach lining) which would be consonant with his understanding of the fond as a digestive space. I thank Michael Naas for lending me his ear to confirm this interpretation. ↩︎

- For Derrida’s direct developments of “autoimmunity,” see Foi et savoir (“Faith and Knowledge”) and Voyous (Rogues). There is much to be said about fascism as an or the proper auto-immunity (or suicide) question of democracy today: from the contemporary cooptation of calls for “fair elections,” the unremitting lie about electoral fraud in 2020, and the bills passed by Republican state representatives in the US, in the name of voter “protection,” which are rather attempts to suppress a portion of the electorate that does not vote Republican, to the Azov Regiment in Mariupol, Ukraine, allegedly connected to far-right, and potentially neo-Nazi movements, while at the same time becoming the last defence of Ukrainian democracy at the siege of Mariupol. One of the most striking and, sadly, traditional examples in the US, of both a rising ground of stupidity and malevolence and an auto-immune impulse, is the purportedly “protection” of life in the Pro-Life movement, which pushes some of the deadliest and cruellest policies and agendas in the name of the indemnity of the foetus. As we know, this violence exerted on women in the name of “life” is part of the auto-immune confusion of the sacred (the attack on the same sacred body one pledges to protect): “violence against women and the sacralization and protection, the indemnification, of them are not opposed but can actually go hand in hand. When ‘real’ women are forgotten, suppressed or repressed, we might even say, the phantasms of them are likely to emerge, their purity made into the object of fetishized desire. When life or life-death is forgotten, when the relationship between life and the technical supplement is denied or repressed, life or life-death is replaced by a hyperbolization of life, the colossal phallus or the spontaneously swollen womb” (Miracle and the Machine, 217). For two recent essays on autoimmunity and suicide in relation to democracy, see Ronald Mendoza-de-Jesús, “Another Life. Deocracy, Suicide, Ipseity, Autoimmunity,” Enrahonar. 66. 2021. 15-35, and Dimitris Vardoulakis, “Autoimmunities,” Research in Phenomenology. 48. No. 1. (Feb 2018), 29-56. ↩︎

- Such an excess as that which exceeds the limits of the demos in modernity continues, to this day, to haunt any definition of the demos as such, and with it, of democracy. As Vardoulakis explains in his analysis of Derrida’s different notions of autoimmunity and their relations to both democracy and sovereignty: “(…) the inscription of autoimmunity as self-critique in democracy to come entails both the inability to give democracy a specific form, either semantically or politically, and the imperative to give it a form, every time anew, within different political circumstances” (Vardoulakis, 42-43, my italics). It is this double bind as the impossibility and simultaneous need to figure, delimit, or (give) form (to) a space next (above or under, in the double sense of “sublime” we will see below) to our recognizable figures (figure and representable bodies), that is best embodied in Jacques-Louis David’s portrait. Or perhaps we should call this painting a “still life” as “nature morte” (dead nature), given the different lives (the lives of the revolution, of Marat, but also of Louis XVI, etc.) expiring, yet surviving, in it. ↩︎

- Such an indecision was remarked by Derrida in his calling his own library, at home, in the attic, in Ris-Orangis, “my sublime”: “… my sublime, my upside down (mes dessus dessous), for I have neither up nor down (car je n’ai ni haut ni bas)” (“Circumfession,” 134; FR 128). ↩︎

- Since we began with Goya’s marsh and will end up with the empty space above his Semisunken Dog, both from the Black Paintings, it is worth noting too the empty space at the top of The Miracle of St. Antonio, painted 5 years after David’s Marat, at the Chapel of San Antonio de la Florida in Madrid. As Anthony J. Cascardi explains, just as with the sovereign emptiness above Marat, here Goya’s critical secularism underlines divine (and royal) vacancy as well: “This is a space that reads as if governed from above by a final vacancy, bereft of any forces that might carry the miracle worker or his father heavenward. The work as a whole derives power from the sheer visual drama of the circular composition and from the steep curvature of the dome, which terminates in a vacant central cupola. Indeed, Goya seems in the San Antonio frescoes to have been responding to the power of empty space—to its ability to suggest the hollowing out of a context that had once been filled with the signs and effects of religious belief.” (36-37). ↩︎

- For an excellent tandem examination of Simondon’s and Schelling’s theory of individuation see, Yuk Hui, “The Parallax of Individuation,” Angelaki, 21 (4) (2016) 77-89. ↩︎

- Such traits make the ground—like khôra and pharmakon—another of those “‘complex words’ that were ‘proto-deconstructive’ in that their philology was shot through with instances of undecidable meanings and senses, if not logics, as well as excessively overdetermined references (explicit or implicit) to kindred terms that multiplied, amplified, misdirected, and contradicted whatever synthesis or positioned meanings one might wish to establish” as described by Herman Rapaport (101). I would also argue that they make it not only such a “proto-deconstructive’ term, but also one of the main figures of any “proto-deconstructive” event, as well as of any proto-constructive one, since the ground is the ineffaceable néotenie of every individuation, the necessary pre-surface to any taking place or topos. For an explanation of “néotenie” as used by Simondon see note 21. ↩︎

- See J. Derrida, “Forcener le subjectile,” in J. Derrida and Paul Thévenin. Artaud. Dessins et portraits, Paris: Gallimard, 1986. ↩︎

- “Its name is not an exact word, not a mot juste. It is promised to the ineffaceable even if what it names, khôra, is not reduced to its name.” J. Derrida, On the Name, 93-94. ↩︎

- In L’individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information, Simondon uses the néoténie (a biological term developed by Julius Kollmann to design the conservation of juvenile characters in adult members of a species) to explain the individuation process by which less “completed” organisms develop as a slowing down of “more completed” organisms, i.e.: “The living beings need physico-chemical individuals to live; animals need plants, which are, for them, in the proper sense of the term, Nature, just as chemical composites are Nature for plants” (153, my trans). This “slowing down” would mark thus a certain “return” to nature or to the pre-individualized process in the new individual. Interestingly enough, this process would make what is traditionally conceived as the “more complex” beings, i.e., humans, the least “completed” ones, the more “inchoatif,” the more “khôratic,” or the most (in their closeness to the indecision of the Ur/Ungrund) auto-immune. ↩︎

- As we have been explaining, this connection between the ground, the origin, and undifferentiation suggests yet another analogy between this ground as pre-individual reality and the Platonic and Derridean notion of khôra, especially as Rapaport examines it in its relation to Derrida’s very early engagement with the question of genesis (in his mémoire Le problème de la genèse dans la philosophie de Husserl), describing it as a “regioned, placed, spatialized” (112) différance. ↩︎

- The relation between the undifferentiation of the origin and the self in Schelling is similar to Deleuze’s and Simondon’s, except perhaps for its theological dimension, positing “the will of the ground” (der Wille des Grundes) as “the yearning of the One to give birth to itself.” (Schelling 59; DE 55). Such theological dimension, however, brings back the question as Derrida posed it in his last seminar, The Beast and the Sovereign, of the impossibility of conceiving a sovereign human identity without the theological notion of divine sovereignty behind it. What is more, it also brings up the question, as Michael Naas has explained in his acute reading of this seminar, of another sovereignty, “a ‘beyond of sovereignty’ as a beyond of ‘the theologico-political,’ something related to ‘Heidegger’s notion of Walten as originary violence, as physis or, indeed, as différance” (The End of the World, 115). ↩︎

- Translatable as “section,” “part,” or “face,” it comes from the Latin “pannus” meaning “piece of fabric,” “band,” “cloth,” itself derived from the common Indo-European “*pan,” which gives a variety of terms meaning “thread,” “fabric,” or even “flag.” ↩︎

- Such a figurability is similar to Lyotard’s notion of the figural in Discours, Figure, especially in its contraposition with discourse as an identificatory and delimited logos. ↩︎

- I want to thank Feargal Whelan for this observation, shared with us in a walk around Beckett’s birthplace and childhood home, Cooldrinagh, in the summer of 2022. ↩︎

- Following these Beckettian examples, it is worth considering if not a similar recognition between Stephen and Leopold is the main theme of Joyce’s Ulysses, with Molly as the final khôratic ground/embodiment where they meet, after having arrived at “Ithaca.” ↩︎

- A brilliant example of the insistence of such cosmogonic figures and their resonances for our anthropocenic, post-apocalyptic landscapes is Pierre Alferi’s novel Hors Sol, where the survivors of the ultimate catastrophe of global warming literally live in a hovering state above the mostly oceanic surface. ↩︎

- As we know, one of fascism’s most puzzling yet direct traits, raised by Deleuze among others, is how a people can will its own repression, its own harm. Or in Derridean terms, how a demos follows its own auto-immune drives. ↩︎

- See Milan Kundera, “An Introduction to a Variation.”

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/98/05/17/specials/kundera-variation.html ↩︎ - I find Zabuzhko’s more general point about “Russian humanism” and its focus on how the criminal is to be pitied instead of condemned—because, as written by Tolstoy “there are no guilty people in the world”—highly relevant in the context of Russia’s current and past crimes. By briefly examining Dostoyevsky’s The Double in what follows as a main example of Western’s modern doppelgänger tales, and how it functions, I would like to explore, precisely, not this piece of literature as “a beautiful princess imprisoned by a cruel regime” (TSL), but rather the violence particular to the Unheimlichkeit of the double, or of reflection, as we still conceive it, in the West, and perhaps also abroad. This is the violence of what and how we identify with someone or something, or not. Such autoimmune violence in the context of our current split tribalistic communities is the focus of Naomi Klein’s excellent recent book, Doppelgänger. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023. ↩︎