Sarah Wood

Independent Scholar

Volume 16, 2024

Let’s begin with a sheaf of epigraphs—even if right now we don’t know what this kind of sheaf is, or how sheaving might work:

1) … the programmer instructs the computer to abide by certain rules, which are then converted into commands to be executed. Activities are ruled by hierarchies, not unlike the military. Such instructions produce a world that is—hopefully—more obedient to the wishes of the commander. The basic linguistic form of computational language is “NOW DO THIS.” Both programmer and military commander fear that the instructions will fail to be transmitted clearly enough, and chaos will ensue. Clausewitz warned of the problem of “friction” which impedes military plans, as they come into contact with messy and changing reality. Good instructions are those which are as clear and simple as possible, with minimal rhetorical or aesthetic flourishes.

William Davies

2) … fascism in the inter-war period was the vehicle for realizing the heady sense, not of impotently watching history unfold, but of actually “making history” before a new horizon and a new sky. It meant breaking out of the ensnarement of words and thoughts into deeds, and using the power of human creativity not to produce art for its own sake, but to create a new culture in a total act of creation, of poesis.

Roger Griffin

3) … the ideas that underlie fascist actions are best deduced from those actions, for some of them remain unstated and implicit in fascist public language.

Robert Paxton

4) The famous spell [fascist leaders] exercise over their followers seems largely to depend on their orality: language itself, devoid of its rational significance, functions in a magical way and furthers those archaic regressions which reduce individuals to members of crowds.

Theodor Adorno

5) I do what I don’t say, pretty much, I never say what I do.

Jacques Derrida

We could think about it like this: four of these epigraphs describe forms of language. They concern how to do things with words, and specifically how language can manage and control people. They form a set of associations and each one makes its own associating moves, observing, guiding, telling, pointing-out: 1) the militaristic ideal of language as a frictionless command operating within a hierarchical order; 2) a fascist conception of radical invention that wants to put an end to the ensnarement of language and thinking altogether; 3) a notion of action as itself readable and as initiating a re-examination of what is being said for its true message; 4) the fascist orator as abuser of language and enchanter of a crowd that becomes mindlessly one as it listens.1 The fifth epigraph doesn’t co-operate with the rest: a resistant “I” impassively refuses to foresee its own moves or to let them be foreseen. It’s an anti-manifesto, an agenda that can’t be deduced or made more explicit because it suggests the interanimation of doing and saying – improvisational, true, already broken up by not-saying or by the unsayable. The first four epigraphs represent analyses of fascism’s lies. The fifth presents (that which is) something else. This provisional distinction between representing and presencing will take us to poetry and music, as places where political and aesthetic thinking happens, beyond the agendas that ask us to put our faith in discourse without improvisation and to separate the sayer from what’s said.

What I am writing may not even happen but power “is always located with the people, no matter the claims of an administration” (The Motion of Light in Water 268). I’d like to go with that, accepting Samuel Delany’s – and Política Común’s – invitation into the uncharted here and now of writing, partly in order to think about “the people” as writers and readers, and how they might do their thing, or rather how we (all of us, speaking more generally therefore more precisely), how we might do ours, short of pursuing a policy but definitely by way of social bonds and resistant movements.

What if “we” being a bundle of “I”s was a fascist myth? What if power were with us—we the readers—and with reading-matter, no matter the claims of an administration? What if reading with love, a certain amount of anger and commitment to hearing and seeing could disrupt the complacency of knowing? What if it can repunctuate space and time? It’s a matter of something like the question: “can you make what we already (do / you remember / how did the people) // have?” (Moten, “fortrd.fortrn” 3). And in this making, there would be nothing like the clearing of an exclusionary laboratory space around poetic or critical experimentation, rather an opening up of the senses to the depth of every little thing already being written on everyday life. For example, a poem might see a lot in how someone dresses: “precision and humility in the experiment / is written on the way you customise your // uniform” (“fortrd.fortrn” 6). Writing can encourage its own fashion-sense or sense of style; reading can emulate the edge of “precision and humility”.

I’m thinking about how to honour the fact that “Deconstruction Contra Fascist Mythologies” declares a particular interest in “deconstruction as a textual and literary event.” And I’m wondering how the “literariness” thing goes with, or against, deconstruction being everywhere, being what happens. Either way, deconstruction is never going to be enough for us. And it’s not as if we have a choice about this or that strategy of relating to a system we could get outside: “the general antagonism won’t let you go, no matter how hard it propels you, ‘cause it’s us” (Harney and Moten, “Plantocracy or Communism” 56). What we have (to learn from, to come back to) is deconstruction as something other than a way of finding things out.

Listening When to Come In

The “general antagonism” can’t be transcended by understanding. It asks more and less of readers than any idea of method, or any thought about how people should read. Fred Moten attacks

a certain mode of intelligence and the supremacy of anyone who could be said to carry it. Fuck that intelligence; exercise, instead, some disruptive, phantasmatic, antepolitical phonography to extend a tradition of discursive violence that passeth understanding.

(“Refuge, Refuse, Refrain” 66)

Disruptive, phantasmatic, antepolitical phonography can make heard what summons and shatters sovereignty. It can appear in deconstruction, psychoanalysis, poetry and critical thought. You could call it by a number of names from the vocabularies of those traditions: batons rompus, indirektheit, anasemia, rub, blur. These are some of the movements we’re engaged in right now. Each one of them does specific violence to any reader’s wish to know in advance what’s going to happen; “on veut s’attendre,” as Derrida puts it, you want to expect yourself, but no, you have to like retracing your steps (“Envois” 8). Batons rompus is the title of a published conversation between Derrida and Cixous, the name refers to broken sticks, French for zigzags; indirektheit or indirectness is taken up from Freud in Archive Fever, and anasemia from Nicolas Abraham in “Fors” and “Me-Psychoanalysis.” And while it is important to note that Moten studied under Barbara Johnson and Avital Ronell, what matters more is how he heard them, and heard them hear Derrida, and is himself “totally interested in how Derrida sounds” and into the rub, in Stefano Harney’s word, of sharing and entanglement (“An Interview with Fred Moten”). Movements are not intelligible systems: they put you in a groove. That’s another way of understanding necessity.

Moten is among us and knows how to be by giving time to edges: where reach exceeds grasp. Reach isn’t just about the length of your psycho-somatic-intellectual-cultural arms. There has always been beauty and sound down around the hem of writing, where the ringing or tinkling of the bells thereof protects life. Language that only serves knowledge betrays the people. Its priests and clerks will come to no good. That phonography Moten refers to, which is a much-needed historiographical energy as well, writes with ears & eyes, gets all the bells and pomegranates ringing and exploding. I’m talking about decoration: a decorative writing with more or less than minimal rhetorical and aesthetic flourishes. In Exodus 28.34-35, the instructions for making the blue sleeveless robe of the priest Aaron are very particular about the fringes:

beneath upon the hem of it thou shalt make pomegranates of blue, and of purple, and of scarlet, round about the hem thereof; and bells of gold between them round about: A golden bell and a pomegranate, a golden bell and a pomegranate, upon the hem of the robe round about. And it shall be upon Aaron to minister: and his sound shall be heard when he goeth in unto the holy place before the LORD, and when he cometh out, that he die not.

(KJV)

The pomegranates were probably tassels in the form of pomegranates, and the whole thing here, with the words spaced and repeated like that, threaded with o and e, is very pretty. According to one commentary on the passage:

The bells were a means of uniting priest and people in one common service— they enabled the people to enter into and second what the priest was doing for them, and so to render his mediation efficacious—they made the people’s worship in the court of the sanctuary a “reasonable service.” And hence the threat, which certainly does not extend to all the priestly garments, implied in the words, “that he die not.” If the high priest neglected to wear the robe with the bells, he separated himself off from the people; made himself their substitute and not their mouthpiece; reduced their worship to a drear formality; deprived it of all heartiness and life and vigour. For thus abusing his office, he would deserve death, especially as he could not do it unwittingly, for his ears would tell him whether he was wearing the bells or not.

(Pulpit Commentary)

This gets taken up by poets. Desirous of being more widely read, Robert Browning published a series of plays and poems in pamphlet form between 1841 and 1846 under the title Bells and Pomegranates. You can be popular and obscure at the same time, if you do it right. Musicians know about that possibility, more than a lot of writers: it has to do with how it sounds. What if the point of so-called literary immortality, were not to cheat death but to start to refuse a certain individuation of the author, and with it the ligatures of the religion of art or literature, marking the true inseparability of writer and readers, priest and people, by means of sound and ornament?

Disruptive, phantasmatic antepolitical phonography writes the history we need because it never stops, and—in Otis Redding’s formulation—it’s a sad sad song anybody can sing any old time. It’s shared with others, draws on the far and near and communes in a way that takes live and on tour what scholars might think of as Derrida’s legendary but thereby somehow over “rewriting of signification as a function of signature effects” (“Translator’s Preface” to Clang, xviii). How could such a writing thing belong to one writer or one place or one time? In a text written with Stefano Harney, Moten addresses fascism directly and finds it to be perennially recurrent and scattered all over—so much for “Strength through unity”:

If fascism is back, when did it go away? In the 1950s, with Apartheid and Jim Crow? In the 1960s and 1970s? Not for Latin Americans. In the 1980s? Not for Indonesians or Congolese. In the 1990s? The decade of intensified carceral state violence against black people in the United States?

(“Plantocracy or Communism?” 52)

Harney and Moten are very clear about adhering to “the black radical tradition’s expanded sense of fascism’s historical trajectory and geographical reach” (52), and this marks something for us to figure out in terms of ethico-political desire. We need to figure out how to get along and go forward; all the bibliographies and works cited and re-cited, all the passed-, past, passing, passed-over and still-coming-into or on-the-way-to-language signatures. And nothing about who arrived first at the gathering, or what it all means, or who thinks they are hosting, will help us to know how to be together, and we do need to know. In Moten’s spoken words “… we need to know something about who and what we are. We need to be able to imagine of … what … what exists in a way that’s sort of more intense I think than the need to imagine what doesn’t exist …” (Moten, “Figuring It Out”). His work implicitly insists on love and does this with a love for what already is, that can also take thinking and writing wherever it needs to go, hatred, scorn, cool and deconstructed high abstraction included.

Much critical material on fascism is concerned to identify the phenomenon and its various forms, going on to establish their aetiologies, symptoms and effects and to warn of their contagious presence in the world today. Two of the works quoted in the epigraphs to the current essay, Robert Paxton’s The Anatomy of Fascism and Jason Stanley’s How Fascism Works, are recent and influential examples of this. There is a lot to worry about, a lot to expose, describe and oppose. This essay follows that antifascist countering, analysis and confrontation by looking out for the living, wayward movement of … what? Marks, sounds, stuff that’s part of what we share and are made of, that was stolen and isolated to assist the ideological project of proclaiming fascism’s existence. The movement messes with some dearly-held intellectual distinctions but we know it when we feel it. It’s in what Robert Browning calls the “no more near nor far” of music (“Abt Vogler” 284) and in other fa-s as well: Aesop’s fable of a father and his sons, as well as certain facts, one of which is that in “fascism” we are concerned with a fiction. Moten refers to a “rampant, violent, brutal, unreality” that can really kill us (“Propositions for Non-Fascist Living—Video Statement”).

Today, reading the recent Hope Not Hate report about far-right extremism in the UK, reading about Ukraine or the Brothers of Italy, or Le Pen chasing Macron in the French Presidential elections, as well as how according to Jason Stanley “America is now in fascism’s legal phase,” we could be tempted to speak of anafascism—after the Greek ana-, meaning “up, back, again, anew.” The term would imply a recognition of the fact that fascism is on the up, coming back, happening again. No good would come of ignoring such a recognition. And yet, recalling Moten, I’d like to get back into temporal pre-conditions that answer a still greater and more real need: the “need to be able to imagine […] what exists in a way that’s sort of more intense […] than the need to imagine what doesn’t exist” (“Figuring It Out”). That would involve a certain hunger to share what reading, writing and performance can do in the way of anfascistic or defascistic unbinding, ana-lytic eliciting, drawing attention to experiences of différance, and generally developing our propensities to imaginative opening. Things people found their way to, even before fascism as we think we know it came to straighten everybody out and get us all on message. I’m also talking about what Irving Wohlfarth describes in terms of stopping. If fascism likes to publicise itself as continuously active, and if historical accounts of fascism inevitably announce presence and continuity in a way that reinforces the combination of fiction and violence—what about receiving its history in another way, in “prose whose discontinuous rhythms and revolutionary punctuation are sensitive to the ever-present potential of a General Strike” (“History, Literature and the Text: The Case of Walter Benjamin” 1009)? Not only prose: don’t those rhythms and punctuations exist in music, painting and elsewhere? Practices that are careful adventures “as we practice / saving differences” (“the red sheaves” 2023, 4) owe precious little to the reigning forms of historical understanding. And as we are concerned here with deconstruction, there is the forebackward movement Jacques Derrida heralds in another context as speaking about old matters, “not only to propose a new ‘exegesis,’ but also to decipher or deconstitute their meaning so as to lead, along new anasemic and antisemantic paths, to a process anterior to meaning and preceding presence” (“Me—Psychoanalysis” 130). Isn’t that the kind of breaking, stretching, melismatic, re-timing, re-breathing and scatter that happens to words and parts of words when they are voiced, in the ordinary course of shared poetic thinking, including lullaby, chant and popular song—a way of making music supremely, if not exclusively associated with the black radical tradition?

Attempts to locate and analyse fascism academically, including using the kind of deconstruction that doesn’t read, will risk losing track of why and how we are joyfully into débris, fallenness, and decorative elaboration, or why, to return to our first epigraph above, Otis Redding’s Complete & Unbelievable Dictionary of Soul starts not with an A, nor with any kind of letter or part of a word, but with a fa.

Redding

In English, to “red” is to clear a space, or a way, to put an end to a quarrel or confusion, to arrange, disentangle, unravel, sort out (OED). If Otis Redding does that kind of thing, it’s not by minimising the flourishes of sound, or by putting his trust solely in words. His composition “Fa-fa-fa-fa-fa- (Sad Song)” opens in a way that puts the chorus and the horns first, where the lead singer teaches the other players by following their sound that he has heard and learned. The song is about singing, and doesn’t hide the fact by pretending to begin with the lyric “I—thou” effect. There is an “I” and eventually a “you” but they are caught up in a repetition of sounds, including just about as many repetitions as the human ear can scan in a single line: “Fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa / Fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa / I keep singing them sad, sad songs, y’all.” It’s a chant, working at the origin of language, a poetic thinking that begins with iteration. Redding’s biographer Jonathan Gould wrote about the singer’s “cavalier attitude towards lyrics and their meaning” (Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life 301), but that formulation doesn’t get to how the whole music moves. The music addresses us right in a kind of feeling—Moten has us here—you can’t know about, you can’t write about because it writes you, having to do with “that thing when aesthetic experience/desire results in the breakdown of individual bodies and their anacorporeal recomportment in and as the mass+energy of social flesh” (“Anassignment Letters” 230). It’s a teaching thing, but also a general originary displacement of the signature which is overrun, dispersed, everywhere, nowhere, everywhere again. It’s somewhat agreed what the roles are, and there’s a willingness to learn but instead of explication, we have “a thing in common” as Rancière puts it (The Ignorant Schoolmaster 3).

You have to decide: are you in the audience, or are you with what’s happening? It’s a summoning and a stopping: “It’ll make your whole body move.” Like when Redding says “everybody do it, one more time,” or elsewhere, like what happens after the break in “My Girl” (for example, the 1966 Ready, Steady Go! live recording). Otis arrests and extends the conversational framework (“talkin’ ‘bout my girl”), by turning the first-person possessive inside-out, with stammer-like repeating syllables that mimic and repercuss, calling up the drums and the horns, also switching addressees, explaining what’s happening in a way that’s gripped by being about to, about to again, having done, not finishing, keeping starting:

my-m-my-m-my girl talkin’ ‘bout, talkin’ ‘bout, talkin’ ‘bout Here’s the story got to tell you ‘bout My-m-my-m-my-m-my-m-my-m-my-m … m’body tell me one more time tol’ me ‘bout ya My-m-my-m-my tol’ me yeah one more time nobody tell me ‘bout my-m-my-m-my-m-my-my … oh

(“My Girl”)

The song itself ends in a perfunctory series of notes from the band. It’s not even pretending it’s over; we’re freed from ending by the suddenness.

Something of this is visible on the undoubtedly quite strange album cover of Complete & Unbelievable, the MY-MY-MY in tall red letters set in front, with Otis wearing a mortar board, smiling, hand on hip, leaning against a giant book: The Otis Redding Dictionary of Soul. He’s dressed as a professor but he’s not here to tell anybody what he knows. As Rancière might formulate it, his mastery lies in the command that encloses listeners in a closed circle (we might see the lovely flat round of an LP),2 from which they alone can break out. By leaving his intelligence out of the picture, Redding allows their intelligence to grapple with that of the music.

This is how we learn my turns into ma, my goodness me, telling us past the horns and through them and the drums into a whole new set of questions Moten asks:

What if intellectual practice is irreducibly chor(e)ographic? What if the animation of the flesh is fundamental to reflection? What if reflection and reflexion and refleshment and refreshment are one in the same? Deeper still, what if the movement in question is, at once, collective and in concert, but also disruptive or deconstructive of the idea of the coherence or integrity of the single body/being?

(“Anassignment Letters” 230).

You can hear what happens to Smokey Robinson’s lyrics for “My Girl” live on Ready Steady Go! with Booker T. Jones, Isaac Hayes, Steve Cropper, Donald Dunn, Al Jackson, Wayne Jackson, Andrew Love, Joe Arnold, Floyd Newman, Patricia Kerr, Cassandra Mahon, Sandy Sarjeant and everybody in the whole TV studio up into the music, as Jeff Dexter recalls: “Every song that was—suddenly played at breakneck speed, you know the dancers had to dance much harder than they had during rehearsal! It was like suddenly the whole show was, was on purple hearts, it was great” (Otis Redding: Soul Ambassador). The analogy also suggests another kind of transportive communing and supplemented oneness, something like Moten describes when he talks about writing as improvising and revising in the company of those not present in real time: “all these people, they’re in my head and they’re in my body, you know, they’re sort of animating my flesh, disrupting the body I guess I thought was mine …” (An Interview with Fred Moten Part I). Lulu gets to the fleshly displacements, animations and disruptions of Redding’s reading with another kind of immediacy: “Otis sort of sang as if his heart was in his throat, and that torn part just pulled at your heartstrings. I think you could totally relate to him. He was a professor, he had got a degree, in knowing how to cut it” (Otis Redding / Soul Ambassador).

Today’s lesson: “Fa-fa-fa-fa-fa- (Sad Song)” is led by a voice calling to, calling up, schooling the Memphis Horns. Steve Cropper recalls:

I don’t know of another man now who has a better sense of communication than Otis Redding. He seems to get over to the people what he’s talking about, and he does it in so few words and little phrases that if you read them on paper they might not seem to make any sense. But when you hear them with the music and the way he sings them, you know exactly what he’s talking about.

(Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life 360).

There’s a staged and probably dubbed performance of “Fa-fa-fa-fa-fa” on video where Otis is play-demonstrating, live-rehearsing, teaching the Horns with that sung horn- or shofar-note, a proto-word-fragment that does something more and less than signify. You can see it on Otis Redding: Soul Ambassador, about thirteen and a half minutes in. It bends our ears, as Derrida puts it, towards a “syllabary put out on the airwaves” (“Rams” 152). Steve Cropper remembers:

Otis kept trying to tell me a horn line he wanted. He was going “Fa-fa-fa-fa-, I want fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-; so wha’ … fa-fa-” So his sounds of the saxophone was that breath, on the reed … fa-fa-fa-fa- … And I said, there might be a song in that: “Fa-fa-fa-fafa-fa-fa-.

(Otis Redding: Soul Ambassador)

In the video Redding’s expressions move quickly and are hard to read: a little weary, irritated, sad, amused. What happened that these people forgot call-and-response? He sings the sounds, turns round to say “Y’alls turn …,” pleased to hear it back from the horns, turns back to the camera “Our turn,” patient/impatient, turning back to the players. He’s a teacher synchronising presence, teaching teaching, bringing everybody to the point, where the point is not the point, but that we’re heading there, pointing at the point that’s inspiration point and vanishing point. What’s to come means you have to come when it’s ready, eat, drink, take part. “Come on, get it!”3

The song comments on what’s happening in its own performance, spacing out time and presence. The lyric refers to the impossibility of changing the familiar run of sad, sad songs that Otis sings because it’s not until the hearers have themselves sung the sad song that this promised, or promises to be, the one in line with all the other sad songs, that the message of that song will be addressed to them and then they will have heard its message, which is what he’s trying to get to them: “when you get through singin’ / My message will be to you.” It all happens and stops happening in the ear, in the passing on and in the flesh, in a line that breaks and zigzags, that isn’t a line until the music hooks you, hooks your heart and makes your whole body move:

It’s a lovely song y’all/ Sweet music honey/ It’s just a line,/ Oh but/ It tells a story baby/ You got to get your message/ A stone message, honey/ A lovely line, baby/ I’m worried a line.4 Watch me.

(Fa-fa-fa-fa-fa- (Sad Song)

He dances sitting down: singing here is dancing as well as teaching. It’s not that he’s a dancer. Wayne Jackson recalled: “Otis always said, ‘if you can’t march to it, it aint’ no good’” (Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life 317). He marches sitting down, beats a rhythm with his fist on his chest, makes eye-contact, prompts the mirror neurons, back inside before the senses enter their classic forms. Getting down in the valley of writing with Solomon Burke, on another march, the same one Derrida reads Nietzsche about in 1965:

It will be necessary to descend, to work, to bend in order to engrave and carry the new Tables to the valleys, in order to read them and have them read. Writing is the outlet as the descent of meaning [French sens, which is also feeling, direction, way, line, even ésprit, which is soul, intelligence, spirit] outside itself within itself: metaphor-for-others-aimed-at-others-here-and-now, metaphor as the possibility of others here-and-now, metaphor as metaphysics in which being must hide itself if the other is to appear.

(“Force and Signification” 35, translation slightly modified)

What happens in the valley, everybody knows, is that you can hear the wind blow, even the four winds that disperse everything. The horns, the breath, the cry, change itself and a power moving through, if only you can hear it. It tells you the most terrible things. You shall fear evil, and nobody will be with you, no comfort, no matter what the Bible says. Redding’s 1965 version of “Down in the Valley” is a precedent for “Fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa (Sad Song).” It has itself a precedent, and the precedent has a precedent. The vocal follows and changes Burke’s 1962 recording, which calls in the Gospel horns on “bad” rather than “fa”: “Did you ever really want someone / Really need them bad, bad, bad, bad, bad?” becoming Redding’s “Did you ever really need someone, oh my / Who really needed fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-fa-ha.”5 Watch the moves communicate, follow the movement. It’s a sexual message, yes, a groove of love is understood, but Redding opens the interpersonal love-song thing, and turns down any presence of comfort, and sings, that is to say breathes with, a pressure, the heavy absent-present airy weightless weight of enigmatically-signified historical significations. They are touched on by Wordsworth’s sonnet to Toussaint L’Ouverture, and countersigned, in the earth and on the sea this time, by Julius Scott in his study The Common Wind, and by Moten’s incredible, all too credible citation and reading of Frederick Douglas in In the Break, where there’s a primal scene going on, and on, and on.

Wordsworth archives but at the same time idealises and individuates, points something out to someone:

Thou hast left behind/ Powers that will work for thee; air, earth, and skies;/ There’s not a breathing of the common wind/ That will forget thee! Thou hast great allies:/ Thy friends are exultations, agonies,/ And love, and man’s unconquerable mind.

(“Sonnet to Toussaint L’Ouverture” 254)

The language: “thee,” “allies,” “friends,” doesn’t really trouble the notion of individuality. The wind is a monument to Toussaint. Julius Scott heads into the archives and retrieves the communication networks that formed a resistance movement across the Atlantic and in the Caribbean in the late 18th century. His research defies prevailing notions of history in general, and the history of transatlantic slavery in particular, as the work of individual agents and national policies. Also in the graphophonics of the black radical tradition, Solomon Burke and Otis Redding carry the news with lyric syncopations and iterations that don’t leave out the too much, the so too much, the too too much, Otis digs into it like a man digging a well, he turns it, and turns to the horn, and flinches at the guitar, so sharp, and turns away but can’t turn away, it gets into the words: can’t turn you loose, you are tiiied and you want to be free, it’s all held in the music that gives it away all over because that’s what you do when it’s too much. I wish I had a way to write about how the instrumentalists—who really are more than instrumental to this— work, how he arranges them, listens to them, redds them and teaches the players what to do while still letting them play. This is Materialist Historiography 1965. What an album title that would be.

Phonocamptic Deconstruction

“Phonocamptic. Adjective (now rare or obsolete) [Greek kamptein to bend] pertaining to (the perception of) reflected sound” OED. So, let’s listen and keep more precise track of the movements of ana-, fa-, ot-, rd-, and all the other sounds that worry our lines and worry them alive, through the phonocamptic reading capacities of black study, so more of us can be trying to tell the story that can’t be told. A quality central to the work of Miles Davis, Cedric Robinson, Will Alexander, Saidiya Hartman and Julius Scott, is a capacity to disconnect, leaving out the obvious notes in a chord, spacing out time in a way that cuts through what seemed like inevitable elements of narrative or exposition, cutting away to something anyone who wants to read, or listen can feel and work with. Elsewhere, sound-bending continues to be torn away from its place in writing history, and historical research still seeks to derive authority from the exclusions and manufactured unbrokenness of Aristotelian storytelling. Scholars keep forgetting what words are for. They are for sharing! It is possible to understand something despite the terror of leaving behind what you know, but not without it. We need to think about why the tracklist of Otis Redding’s Complete & Unbelievable Dictionary puts “I’m Sick Y’all” ahead of the tainted waltz, and how anger that refuses to be restricted to anti- and non- best carries the news, which isn’t good and weighs heavier than a death in the family.6

Derrida scholarship mustn’t look too hard for a way out of what sickens it, lest we forget what he says about reading. When we read and write there are signatures that are not simply present. We carry them, sometimes without knowing it. Carry: “Bear from one place to another, convey, transport, (by vehicle, ship, aircraft, etc.; on horseback; on a river, the wind, etc., by its own motion; on the person, in the hand, or fig. in the mind” (OED). To read is to be with those people and things, sometimes without knowing it, to raise them up on the earth, in the water, through the air. Cixous describes how reading takes us into “a living-dead, absent-present-relation, a spectral relation with the presumed signatory or signatories or the presumed signatory scene of the text” (“Volleys of Humanity,” 264). She wrote that in a text from 2009, reading and writing with Derrida, who left in 2004, and is being interviewed on the occasion of a Fête de l’Humanité in 1999.

We always carry on by disappearing into a scene. Moten also knows about this, mutatis mutandis, ana = dispersed mama as he says, you do the math, in the absence of any way of saying “equals” without saying “subordinates.” The debt that can’t be paid is no myth:

Our writing needs to be free to take the form of zigzags and bunches of stuff that are beautiful not because of what they mean, that’s maybe unteachable, but because these forms let us imagine what already is, and want it more than ever, like when Moten is listening to the paintings of Jennie C. Jones and responding so that we start to desire history again for the first time, and Derrida is there too. I’ve already quoted Moten’s “the red sheaves” and I’m going to quote an earlier version here, the one that’s in the brochure for Jennie C. Jones’s exhibition Constant Structure. The earlier version has more of the scholarly references we need. For this dossier on deconstruction contra fascism, it’s useful that Derrida is named and his work on structure, sign and play cited. (There’s also a breath of the wind under the wings of Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History). Here’s what Moten calls for:

We want what Jacques Derrida calls “structure without a center,” a progression in which chords of the same quality but with different root notes are played consecutively, giving what they say is a free and shifting tonal center, which seems to mean that if the center shifts, then it is not. Then, it is a fugitive center, an eccentricity, which brings to mind a changing, shifting structure, a moving structure, a structure that can be felt—nonsensuously—in being seen, or even heard, to be more + less than cool reason ever comprehends. A structure of wind, or breath, or even of a range of absent wings and tongues who, nevertheless, make their impression. An open, mobile togetherness, a tumultuous gathering, a murmuration, like the recoil or the recall of some birds reciting aesthetic informality without an art form or an artist.

(Moten, “The Red Sheaves” 2020, 10)

He keeps calling in ways that keep on by changing. Moten’s fashion of revising is suggestive for our understanding of how deconstruction has always had to change. The revised version of the passage above is in perennial fashion presence falling pages 12-13, and it retains a lot but erases Derrida’s name. The published writer is gone, part of the range of absent wings and tongues, while a reference to “jackie-marching” transposes JD to the now more recognisable and more fully musical displacements of (Thelonious Monk’s 1959) “Jackie-ing” and how that music marches, shifts and sheaves. Monk’s “Jackie-ing” multiplies rhythms and skips what’s expected, and deserves a more musically literate account than I can give. But still, I can hear it keeping the same condensed, hard-dancing energy of marching that Otis Redding’s onstage marching moves carry, while Moten also makes “jackie-marching” this phrase that laughs at any wish to keep in step with, or merely keep up with that energy, recalling that Derrida renamed himself Jacques the better to publish his academic work, but it was back then as Jackie, the Jewish child caught in the frictions of German-occupied French-occupied Algeria that he made the initial libidinal investments that make his writing capable of being, and knowing itself to be “a march, an act, an appeal, a demand” (Monolingualism of the Other 72). The common noun or gerund “jackie-marching,” with a lower-case “j” also recalls the “something that exists between” Derrida and Monk, “that rub, that hapticality” as Moten describes it in some remarks on the unmistakable closeness between Marx, Freud, Derrida and the black radical tradition (“An Interview with Fred Moten Part II: On Radical Indistinctness and Thought Flavor à la Derrida”).7

Shake! Ébranlement. Embranglement.

Got to, got to shake. “Words”—Cixous reminds: “—what chance and what energy!” (“Writing Blind” 121). But in order to claim fascism’s legitimate presence and historical necessity, to found its identity and name, it had to happen that certain words, symbols and movements could be turned in and conscripted into a lying war on truth. Their possibilities were noticed, taken and put to use in a story. So much depends on our incredulity and refusal when we see thinking, history and language forced to uphold any kind of -ism. So much depends on how we read, and where, and with whom. Cixous tells it pretty clearly: “We are reading, in the morning as soon as it is day, we read – from the cradle, from the first gaze, already we are reading. We are giving ourselves to (be) read. We are making links. We are mirroring ourselves in the mirror of the other” (“Volleys of Humanity” 264).

It’s that “we”: “First we feel. Then I write. This act of writing engenders the author” (“Writing Blind” 118). It makes us tremble, even when it’s a good vibration it’s an earthquake feeling. Stefano Harney and Fred Moten describe writing together as: “that touch, that rub, that press, that kinky tangle of our incomplete sharing” (Conversación Los Abajocomunes). This is how we patch nonsense into sense, how we study, by descriptive ear: we have to go somewhere with people who can take us with them, who become able to take us by doing so even before we know we’re setting out. Moten mobilizes, assembles, sheaves, shuffles with a shared and riffing ear for the form-generating force, the disparate genius of black social and aesthetic life. What’s more he can describe what’s going on: “collective, space-time separated testimony in the form of deconstructive gathering, destroying and rebuilding, profane and sacred space blown up and out from the inside, surreptitiously” (“Refuge, Refuse, Refrain” 65). Moten gets us believing again in the sense no one ever made, without explanation, like Cixous writing blind, like looking at something a long time, in dark, dark, dark, amid the blaze of noon.

At stake are the concomitant social effects of a kind of reading that can hear and see writing, that cannot help but imagine words as things, or experience them as movements not confined to signification. There are subtle definitive hatreds that will sideline reading by patronising its greatest proponents and finest moments, speaking of “playfulness” or “creativity,” enviously celebrating its “freedom” and associating it with this or that “marginal group” (women, black people, poets, children, sensitives, the avant-garde, the mentally ill, the ones who are not fully present, don’t read the news, license themselves to pleasure and idiosyncrasy). However, they cannot entirely suppress the existence of reading as a visionary experience of divination among the general writing. Another sheaf of epigraphs to open an essay on deconstruction and the myths of fascism. No numbers this time. Picture them never entering your mind, playing softly and irreversibly, with a red garland:

The historian’s qualifications hinge on his sharpened awareness of the crisis into which the subject of history has entered at any given time. This subject is by no means a transcendental subject but rather the militant oppressed class in its most exposed situation.

Walter Benjamin

I had a sense Dotty’s mid-fifties infiltration of that all-male space had been a political turning point. Also it carried a lesson about power (as opposed to material strength, with which power may or may not be enforced): It is always located with the people, no matter the claims of an administration, and may be defied as easily as pristine ignorance’s stroll across a bar’s dark floor planks.

Samuel Delany

Let the emblemed philosopher be thus fixed.

Jacaues Derrida

I note, I want to write before, at the time still in fusion before the cooled off time of the narrative. When we feel and there is not yet a name for it.

Hélène Cixous

We feel? Fuck the flow.

Fred Moten

Emblazoned, right on fascism’s name, is a device, the picture of a bundle or sheaf, a logo on a reading-shield that diverts our reading, giving rise to non-semantic effects as well as symbolic substitutions. It’s a falsifying figure for what I follow Delany in calling “the people.” The people who cannot be bound to themselves, who are not a crop or a unified collection but a changing same and a desired embranglement of differences. Fascism lies about us and to us. Sometimes its device is in plain sight, borne in a ceremony, carved in stone and fixed to the front of a building, printed on a bank note. Other times it works more discreetly to shackle one thought to the next until thinking and history cease to be worthy of the name. The image magically arranges the scene around itself, ordering knowledge, history, language so as to make it impossible to imagine any movement not dictated in advance by hierarchies too banal to name. What exists is acknowledged and forgotten in the same movement. It is as if the movements of the people could not be imagined. But we do imagine them. We can counter the lie. Delany imagines “pristine ignorance’s stroll across the dark floor” into the forbidden zone (The Motion of Light in Water 268). It happened: he heard about it and told us. This is history. Moten imagines another way of phrasing change by imagining Jennie C. Jones and Amiri Baraka’s way of imagining what exists, too. I’m going to cite the brochure version of “The Red Sheaves” here too:

And what about this totally cool semantic phenomenon in which the word “constant” in the phrase “constant structure” can only ever seem to imply change? Change is its semantic substrate so that “constant structure is another way of phrasing what Amiri Baraka keeps aberrantly calling “the changing same.” This phenomenon of sustain ed delta, in which constancy implies and bears change, because if the structure is to be constant it must change, indexes or ondoctes or echoes that imperative against its anamonolithic grain, carrying changes out from the enclosure of subject, object and decision.

(“The Red Sheaves,” 2020, 4)

This beautiful word “anamonolithic” is only in the earlier version of the poem, and it describes the layout of the poem on the page, its justified lines and fluidly spaced typography, also the spacing and the plain surfaces of Jennie C. Jones’s painting, hung for a show that people can move around. Monoliths otherwise. Pillars, differently. Two-dimensional columns addressing our condition of unshakable uprightness, angularity and petrifaction in a roundabout, oblique manner. Just walking around, as John Ashbery says: “Come see it. Come not for me but it.” (“Just Walking Around” 8). As if you could just walk around in the writing or in the painting, get inside it, where it welcomes you with light and mystery and food. Paintings address our presence with attention to the varying densities and feels evoked by surfaces. We can call these surfaces “fascia”: (“Any object, or collection of objects, that gives the appearance of a band or stripe” OED). They speak to our sense of inside too, to our felt sense of connective tissue’s thinness and capacity for slip and rub that connects as it binds the other tissues and organs of the body. Collective tissue, I meant to say, amis lecteurs; we like running on, and looking back, and being with the “presumed oppositions or contraries” Cixous talks about (“Volleys of Humanity” 265). Derrida readers have no right to miss what Fred Moten is talking about because he’s showing us how to go, how to move through, very gently, what moving on looks like when we remember how to read:

Because we want to see what it will be like to submit to no design, to be undevoted to our line breaks, to have them only ever come from having been broken, cut, cut off, or having been surprised by the real in the neighborhood, like when we come upon what comes up on us from behind, while we be walking straight ahead, eyes wide open, over the rentpartying cliff of some threshold, having walked right through the bend in Betty Carter’s river, through the scent of the heather, in the shimmering, in the wreck, all up in the water, remember, with all them birds, because, in our shared attention to edges and margins, we are certain in nonfull nonsimplicity, tuning, turning.

(“The Red Sheaves” 2020, 28)

Without that imagined togetherness, that bliss-ridden drift towards the edge, where waiting and promise and presence blur, and without what that movement makes possible, which is a most unblissful experience of the edge, it’s as if the whole deconstruction thing were no more than a fable, an example of itself, an explanation from Aesop, or worse a premature fantasy of rescue from the wreck and the cold gray-blue gaze of the indifferent sea.

Don’t Read the Instructions

An old and dying man, let’s call him the Famous Inedible Patriarch:

… asked his sons to bring to him a bundle of slender rods, if there happened to be some lying about. One of his sons came and brought the bundle to his father. “Now try, with all your might, to break these rods that have been bound together.” They were not able to do so. The father then said, “Now try to break them one by one.” Each rod was easily broken. “O my sons,” he said, “if you are all of the same mind, no one can do you any harm, no matter how great his power. But if your intentions differ from one another, then what happened to the single rods is what will happen to each of you!”

(‘The Old Man and His Sons,’ Aesop’s Fables 227-28)

They never said a word. One of them just fetched the sticks that were lying around, then watched and learned the lesson. The motto was maybe Strength in unity or Solidarity, or perhaps that should be Think alike or No difference without separability. The fable in general always risks saying: Read me! The condition of your reading is an identification with the entire explanation of the other. More concretely, according to a living-dead scene conjured by Anthony Marshall, the ceremonial Roman fasces were not a message that could always possibly go astray, they were a direct threat to life:

the fasces were not merely decorative or symbolic devices carried before magistrates in a parade of idle formalism. Rather, they constituted a portable kit for flogging and decapitation. Since they were so brutally functional, they not only served as ceremonial symbols of office but also carried the potential of violent repression and execution. If these emblems of office paraded before Roman eyes retained their practical function in the infliction of severe corporal punishment, then despite the advent of provocatio their punitive associations never became as historically “distanced” for the average citizen as have those of ceremonial maces and swords in modern societies. Even after provocatio had been won to shield citizens from their summary use, mass executions of deserters or prisoners of war involving virgae [the rods] and secures [the axe] could still be viewed on occasion in the forum. Roman society was therefore unusual in that its central magisterial regalia remained directly functional; the fasces continued as both symbol and instrument of executive power. Thus, powerful emotions of pride and fear could focus on them, and their symbolic political significance was accordingly intensified by their aura of latent violence.

(“Symbols and Showmanship in Roman Public Life” 130)

There’s a certain contempt in the phrases “merely decorative or symbolic” and “parade of idle formalism.” This piece of history disregards Delany’s distinction between power and the material strength with which power may or may not be enforced. Its description universalises and accelerates a movement in which recognising the fasces meant one thing: the hierarchical symmetry of brutal teaching and calculating comprehension. It imagines an onlooker with just enough knowledge to be interpellated into an order that depends on granting or refusing citizenship, just enough wit to recognise the fasces’ potential as weaponry, and just enough imagination to hear it say: Freeze! This approach has got to be displaced, subjected to ructions and brought towards the people who can help figure it out. It’s a scene that still happens in schools of every kind.

Latin fasces, in Italian fascio: for some these signifiers still hyper-connect twentieth-century Italy and ancient Rome:

The word fascism has its roots in the Italian fascio, literally a bundle or sheaf. More remotely, the word recalled the Latin fasces, an axe encased in a bundle of rods that was carried before the magistrates in Roman public processions to signify the authority and unity of the state. Before 1914, the symbolism of the Roman fasces was usually appropriated by the Left. Marianne, symbol of the French Republic, was often portrayed in the nineteenth century carrying the fasces to represent the force of Republican solidarity against her aristocratic and clerical enemies. Fasces are prominently displayed on Christopher Wren’s Sheldonian Theatre (1664-69) at Oxford University. They appeared on the Lincoln Memorial in Washington (1922) and on the United States quarter minted in 1932.

(The Anatomy of Fascism 4-5).

Italian revolutionaries used the term fascio in the late nineteenth century to evoke the solidarity of committed militants. The peasants who rose against their landlords in Sicily in 1893-94 called themselves the Fasci Sicilani. When in late 1914 a group of left-wing nationalists, soon joined by the socialist outcast Benito Mussolini, sought to bring Italy into World War I on the Allied side, they chose a name designed to communicate both the fervour and the solidarity of their campaign: the Fascio Rivoluzionariao d’Azione Interventista (Revolutionary League for Interventionist Action.) At the end of World War I, Mussolini coined the term fascizmo to describe the mood of the little band of nationalist ex-soldiers and pro-war syndicalist revolutionaries that he was gathering around himself. Even then, he had no monopoly on the word fascio, which remained in general use for activist groups of various political hues.

Officially, Fascism was born in Milan on Sunday, March 23, 1919.

This history of a word inside a much larger and more detailed project of describing “the major political innovation of the twentieth century” (Anatomy of Fascism 3) needs to be cited, and read, but it can’t really be part of what we need to imagine without getting bent out of shape. Historical writing has a way of arranging things, it lines up signifiers and proper names. The various terms, fasces, fascio, fascizmo and so forth signify and communicate, we are told, authority, unity, Republican solidarity, the solidarity of militants, the fervour and solidarity of leftist nationalists. Fascism the word, fascio, fasces, fasciszmo, Fascism the new-born political abomination; Italian, Latin, Roman, Left, Marianne … Fasci Siciliani … The more history we read the harder it seems to say what fascism and its cognate words should be called, linguistically speaking, in what language they belong, whether they are signifiers, signifieds, names, symbols, things, regalia, weapons, synecdoches, metonymies … and the harder it is to satisfactorily distinguish and position them in what Moten calls the “enclosure / of subject, object and decision.” No one gets to monopolise the discrepant agency of words. Their energy remains available for general use (citation and recitation), even when put to work telling this or that story.

According to our first set of epigraphs, fascism wants to be all about action, intervention, the most accelerated decipherability of language in general, but we are here to remember the revolutionary historiographical potential of aesthetic discontinuity, what Irving Wohlfarth calls the “dynamite that is to explode the continuum of history” (“History, Literature and the Text” 1009). When reading is figured as a series of punctual acts of representation, portrayal, display and appearance, it could seem as if that’s all there is to it. No way. Roots are routes. Recollection can be animal: “a murmuration, like the recoil or the recall of some birds reciting aesthetic informality without an art form or an artist” and “all up in the water, remember, with all them birds, because, in our shared attention to edges and margins, we are certain in nonfull nonsimplicity, tuning, turning” (“The Red Sheaves” 2020, 28, 10). It’s an experience we have, unfolding and ravelling in the ordinary ensemblic behaviour that might be called “general reading.”

Gleanings from the General Sheaving

Fasces, Latin for a bundle or sheaf: OK, but the word is more plus less than a harvested quantity, the consistent bundle or package of some self-identical substance, wheat or rice, that holds its form, publicises this or that historically determined social order and fetches an agreed cognitive price. As Moten and Fernando Zalamea help read them, sheaves are also something less concrete: a proto-investigative formation devised by 20th century mathematics to work precisely with the shared and already sharing, gathered, dispersed and interspersed condition we find ourselves in. This mathematical sheaf can’t be visualised in the form of an emblem, though there are some pretty fierce diagrams out there. The mathematician and philosopher Zalamea describes the necessary work of cognition beyond unitary recognition as follows:

To construct a sheaf on some space allows us to “shift the discourse” from something less well-understood to something better-understood by ensuring that the less well-understood object is faithfully patched together from regions of better-understood structures – and this even though the better-understood structures in themselves may initially appear to have nothing to do with the less well-understood object that we want to study.

(“Wittgenstein Sheaves” 3)

A sheaf can thus be regarded as an answer to the following question: what kind of rule turns local nonsense into global sense? More suggestively put: A sheaf is a rule to patch together nonsense into sense. And if we are in possession of a sheaf then we can literally replace our object of study with a sheaf defined on it – and proceed to study that sheaf, forgetting all about the object we started with. This simple but vague idea of a sheaf was of monumental significance in 20th century mathematics.

These remarks come from a fascinating experimental essay published by Zalamea under the name of Cosmas Capros. Inventive in terms of form, tonality, its deployment of surprising rhetorical gambits and combination of intellectually challenging materials, the essay takes up mathematical sheaving to understand late Wittgenstein. It describes (and indeed intentionally practices) insight as “that which you do justice to, not [that which you] attempt to communicate” (“Wittgenstein Sheaves” 18). It deserves and repays study. Insight, the essay suggests, does not primarily exist to hold itself up for the general approval by using this or that (here, mathematical or philosophical) material to substantiate itself. It is an experience both given and hard-won, hidden and yet unmistakably evident in the essay’s manifold broken but precise and informative “zigzag” movements (“Wittgenstein Sheaves” 1). This differentiates its insightful account of sheaving from the totalitarian fascistic binding of sticks, and stick-people, under the “famous spell” of a single voice (Adorno, “Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda” 132). “Wittgenstein Sheaves” is more interested in finding things out than in marshalling evidence towards a conclusion, and it customises its essay-uniform with precision and humility. The fascist sheaf represents, for an imaginary or self-imagining set of individuals dragged into strict formation and set on course for a single end. Sheaving, on the other hand, presents what is necessary for understanding in a faithfully patched-together way, and this must include some sense of who you’re talking about, and who you’re talking to, and the necessary tact and grace to be with them without imposing too much being of your own.

Zalamea’s book Synthetic Philosophy of Contemporary Mathematics points to an incessant exercise that sheaving asks of those who are interested in it. (Elsewhere, Moten talks about works that do not “constitute an end within an eschatological system [but], rather, a remorseless working in a general field of … beginningless endlessness,” “Discomposition: An Interview with Fred Moten”). For Zalamea, working in the field of mathematics, cuts and ruptures are necessary for mathematical understanding, which draws on sheaves to find ways to include that which cannot simply be reconciled:

In concrete terms, sheaves, those (quasi-) objects indispensable to contemporary mathematics, acquire all their richness in virtue of their double status as ideal/real, analytic/synthetic, local/global, discrete/continuous; the mutual inclusion (and not the exclusion) of opposites—an incessant exercise of mediation—secures their technical, conceptual and philosophical force.

(Synthetic Philosophy of Contemporary Mathematics 288).

The doubleness Zalamea talks about is a major formal element in “WittgensteinSheaves,” which divides itself in two. The upper two thirds or so of each page is the reading of Wittgenstein’s later work, to be read left to right in the usual way. The lower third is presented so as to be read backwards from the last page of the essay to its first and describes in a personal, even diaristic way the painful erosion of the writer’s subjectivity. In the process of showing “that the method of the late Wittgenstein is to construct a sheaf of objects-of-comparison defined on our natural language” he is “floored” and “struck” by the realisation that mathematics and philosophy are not modes of discovery or ways of finding things out but activities you do without thinking, comparable to the jumping of cats or the spinning of silkworms (“WittgensteinSheaves” 4, 22-20). Sheaving entails a refusal of transcendence through knowledge; its way of making sense has everything to do with imitation.

And how might this affect our understanding of the red sheaves that Moten writes about? No list could do justice to what he brings together. The revisions of the poem already enforce a double reading. The more note-like and scholarly 2020 version of “The Red Sheaves” appears alongside and reads Jennie C. Jones’s Constant Structure paintings, and cites the names of many writers, artists and musicians (Jones herself, Renée Gladman, Derrida, [Bernhard] Riemann, Amiri Baraka, Wilson Harris, Betty Cartwright, Miles [Davis], Herbie [Hancock] and so on). The 2023 poem has gone on to become something differently spaced, more opened out on the page, tougher to quote from, more idiomatically and clearly and at times cryptically insistent on being in conversation with a black “we.” Complexity and condensation are even more there and it seems still less possible and still more wrong for a critic to itemise the intensity of the writing as it displaces, skips and erases. I have already quoted the passage from the 2020 version that names Derrida and the 2023 revision that jackies him under Monk’s wing. Both versions gloss sheaving, I think, but it’s clearer, glossier, blacker and musically faster in the later version, when it describes how the “jackie-ing march” goes:

where some same/qualities with different/roots play parallel,/ giving free amd shifting/ nothing eccentrinsically,/ nonsensually depth-felt/ but cool/in being seen+heard/in how to/ to be more+less than reason comprehends,/stay/ in how we just can’t stay/ and how we can’t just stay.

(“the red sheaves” 2023, 13)

It’s also so obviously talking about black socioaesthetic life, including music, that I don’t want to emphasise the sheaf-thing too much. It’s also that these sheaves Moten mimetically and ana-emblematically writes can’t not include people whose ancestors were torn away and stolen in a calculated harvest, enumerated in ledgers and enslaved in the plantations, along with a desire those people and their ancestors might have to gather and paint pictures, or be with music or poetry, or to cook and talk with each other so as to counter brutal, murderous calculation with improvisations coloured and sounding from felt depths of insight. If you were to listen to the “the red sheaves” being read you might hear and see the Red Sea parting, clearing, separating, closing the waves of reading, of Fred reading, of sheaves having been read by Jennie Sea Jones, all those ears up in the perennial grass, listening, and the red, plain red, colour she uses in the paintings Moten calls “a black / and red sea’d haptic / operation” (“the red sheaves” 2023, 8). And there’s a kind of redding going on, a redding kin like when you respectfully unravel family history while being folded up into a learning of visits and conversations with elders and friends, a living spectral arrangement of talk that dispenses with what writing traditionally fences off with its distinctions between capital and lower case letters and proper names and common nouns. And maybe there’s some defeat of the kind of red flag that says stop, more of the communist kind of red flag that Walter Benjamin and Walter Rodney unflaggingly advocated, that waves to say gather, stay, strike! and points to “the lie that harmony exists” (Groundings 65). It strikes my memory that Fred Moten and Stefano Harney insist on black study not being about any “object,” and they sheaf and teach sheaving when they talk about what they do, and that Derrida sheaves too. For example at the start of Clang, when he collages scraps of “what remains today, for us, here, now, of a Hegel,” not starting from the casually recognisable individuality of public Hegel, the “emblemed philosopher,” but with leftovers, philosophical traces, in a dispersing haze of signatory smoke, addressing those few random guests ready to stick around till the morning after, cooking up something dangerously palatable in the palpable atmosphere of signatures that can’t be deciphered because they are too many, too weakly strong, working “much later and slowly this time” to exhibit the edges and margins of a certain philosophical code of knowing (Clang 7a).8 Can’t stop reading that page, but don’t want to get past Moten’s gentle declaration right at the start “we’re walking / an open diary” (“the red sheaves” 2023, 3), which I take to be a friendly refusal of hasty assimilation, and therefore as a resistance to the assimilative drive whose most extreme ideological product fascism is.

With Miranda Wood, Tom Tomaszewski, Forbes Morlock, Ben Grant, Kaori Nagai, Yuli Goulimari and more.

Notes

- The fourth epigraph explicitly valorises reason and individuality in ways we will need to look at again, in this essay and elsewhere. Adorno’s “Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda” pathologises fascism’s followers in ways that resonate with his account of jazz as a “mass phenomenon” (“Perennial Fashion—Jazz,” 119). As this essay tries to find out about deconstruction’s countering of fascism by way of Otis Redding’s soul music and Fred Moten’s poetry, it must at least acknowledge that Adorno hates black music and that his phobically fascinated writing on jazz pathologises black social life. Moten’s latest collection of poems (2023) is called perennial fashion presence falling and it dispenses with, we might say disperses Adorno by putting that phrase perennial fashion to use against the perennial wish some people get behind, to separate art from social and aesthetic practice. In a recent interview, Moten points out the relationship between his book and Adorno, and asks: “But what if the problem with Adorno is that he loved jazz, but he just couldn’t admit it? That the anti-blackness of his intellectual formation was so powerful that to admit that you love this music and even further, to admit that this music bears thinking, would have been to throw over his entire intellectual formation. I don’t think he could do that. In many respects he’s a more or less deviantly orthodox Kantian, and nothing good can come from that kind of thing. Maybe what I’ve been trying to say is that this residual Kantianism is a general problem that causes particular discomfort for the ones who don’t want it that way or who want to assume that for them it’s not that way.

But to me, to the extent that jazz has a definition, the best definition ever is Adorno’s definition, which is: “jazz is not what it is.” You know, like, yeah, okay, that’s right. So, it’s interesting that out of all that hate came all that truth”

(“Discomposition: An Interview with Fred Moten”). ↩︎ - The record lends its form to what’s going on here: a circular shape, a fixed location, track order and duration, and the possibility of the kind of repetitive immersion in sound that repeats the conditions under which children first learn to speak. ↩︎

- Moten’s great critical poem of that name, that is not only his, and carries many names can be read across a number of his books: parts 1-11 appear in The Feel Trio 35-64, parts XIV-14-20 and 21-25 in all that beauty 5-24, 113-122. I’m looking for parts 12 and 13. ↩︎

- The lyric sheets give “worried in mind” but you hear “worried a line,” or even “worried alive.” ↩︎

- Burke recalled in 2006: “I wrote that on the train, ‘cos I had no song and I started thinking on old songs that I could do uptempo and I thought, (sings Gospel song pacier, with horn arrangement) so I had to keep that in my head ’til I got to the studio. I said, ‘Can I have a tuba like I have in my church?’ In my church we got the tuba and the trombones. Got to get that New Orleans sound. They loved it.” (https://www.songfacts.com/facts/solomon-burke/down-in-the-valley) ↩︎

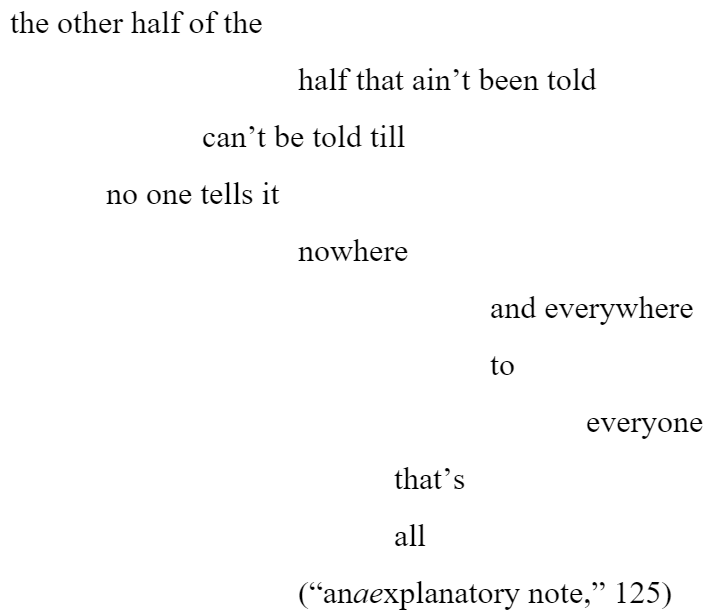

- Read Moten, “anaexplanatory note,” all that beauty, 124-26; also In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, especially 18-24. ↩︎

- There’s an important reading of both versions of “the red sheaves” in a fine review essay of perennial fashion presence falling by Coleman Edward Dues in The Cleveland Review of Books (“Some Ekphrastic Evening: on Fred Moten’s perennial fashion presence falling,” The Cleveland Review of Books, February 1, 2024 https://www.clereviewofbooks.com/writing/fred-moten-perennial-fashion-presence-falling).” ↩︎

- I have been reading Clang / Glas since the Glossing Glas symposium with Derrida in Kolding, Denmark in 2002. A little of what was presented there is published in “Not One of My Moments” Derrida Today 10(2) 160-179). ↩︎

Works Cited

- Adorno, Theodor. “Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda.” In The Essential Frankfurt School Reader. Andrew Arato and Eike Gebhart. New York: Continuum, 1982, 118-137.

- Aesop’s Fables. Translated by Laura Gibbs. Oxford: World’s Classics, 2002.

- Ashbery, John. “Just Walking Around.” A Wave: Poems. New York: Penguin Books, 1985. 8.

- Browning, Robert. “Abt Vogler: After He Has Been Extemporizing Upon the Musical Instrument of His Invention.” In Robert Browning’s Poetry: Authoritative Texts, Criticism. Edited by James Loucks, Andrew Stauffer. New York: W. W. Norton, 2007, 283-85.

- Burke, Solomon. “Down in the Valley.” The Very Best of Solomon Burke. Atlantic, 1962.

- —. “Down in the Valley.” Songfacts. https://www.songfacts.com/facts/solomon-burke/down-in-the-valley. Consulted April 4, 2022.

- Cixous, Hélène. “Volleys of Humanity.” Translated by Peggy Kamuf. In Volleys of Humanity: Essays 1972-2009. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2011, 264-85.

- —. “Writing Blind: Conversation with the Donkey.” Translated by Eric Prenowitz. In Stigmata: Escaping Texts. London and New York: Routledge, 2005, 115-125.

- Davies, William. Nervous States: Democracy and the Decline of Reason. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020.

- Delany, Samuel. The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

- Derrida, Jacques. Clang. [1974]. Translated by David Wills and Geoffrey Bennington. London and Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

- —. « Envois. » La Carte Postale: de Socrate à Freud et au-delà. Paris: Flammarion, 1980.

- —. “Force and Signification.” [1965]. Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass. Routledge: London, 2001. 1-35.

- —. “Me—Psychoanalysis.” [1978]. Translated by Richard Klein. In Psyche: Inventions of the Other I. Edited by Peggy Kamuf and Elizabeth Rottenberg. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007. 129-142.

- —. Monolingualism of the Other. Translated by Patrick Mensah. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998.

- Jonathan Gould. Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2017.

- Griffin, Roger. Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- Harney, Stefano and Fred Moten. Conversación Los Abajocomunes.

- Conversation on the occasion of the Spanish translation of The Undercommons by Yollotl Gómez Alvarado, Juan Pablo Anaya, Luciano Concheiro, Cristina Rivera Garza and Aline Hernández. The New Inquiry. September 5th, 2018. https://thenewinquiry.com/conversacion-los-abajocomunes/ Consulted January 26, 2022.

- Harney, Stefano and Fred Moten. “Plantocracy or Communism.” In Propositions for Non-Fascist Living: Tentative and Urgent. Edited by Maria Hlavajova and Wietske Maas. Utrecht, Cambridge MA and London: Basis voor Actuelle Kunst and MIT Press, 2019, 51-63.

- Harney, Stefano and Fred Moten. Propositions for Non-Fascist Living – video statement. BAK Basis voor Actuelle Kunst. Youtube, October 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZxZir6POGb0 Consulted January 24, 2022.

- Jeremy Marre. Otis Redding: Soul Ambassador. London: BBC4, 2013. Archived at https://vimeo.com/240581042. Consulted February 15, 2022.

- Marshall, Anthony J. “Symbols and Showmanship in Roman Public Life: The Fasces.” Phoenix 38(2): 1984. 120-141.

- Moten, Fred. all that beauty. Seattle, WA: Letter Machine Editions, 2019.

- Moten, Fred. “Figuring it out.” Youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmnFeGaCkGI. Excerpted from Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, April 24th, 2015. The Poetry Project. https://soundcloud.com/poetry-project-audio/stefano-harney-fred-moten-april-24th-2015 Consulted January 31, 2022.

- —. “fortrd.fortrn.” The Little Edges. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan UP, 2015. 3-9.

- Moten, Fred. “Refuge, Refuse, Refrain.’” The Universal Machine. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018. 65-139.

- Moten, Fred. “The Red Sheaves.’” Constant Structure, brochure produced on the occasion of Jennie C. Jones: Constant Structure. The Arts Club of Chicago, March 19–May 22, 2020. 3-34. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5526ca35e4b02b6cae98841c/t/5e8644ec1b1008571750e24e/1585857789526/FINAL+Constant+Structure+Moten.pdf Consulted January 24, 2022.

- Moten, Fred. “the red sheaves.” perennial fashion presence falling. Seattle: Wave Books, 2023. 1-21.

- Moten, Fred and Andrew Fitzgerald. “An Interview with Fred Moten Part I: In Praise of Harold Bloom, Collaboration and Book Fetishes” Literary Hub. August 5, 2015. https://lithub.com/an-interview-with-fred-moten-pt-i/. Consulted February 27, 2022.

- —. “An Interview with Fred Moten Part II: On Radical Indistinctness and Thought Flavor à la Derrida.” Literary Hub. August 6, 2015 https://lithub.com/an-interview-with-fred-moten-pt-ii/. Consulted February 27, 2022.

- Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism. London: Penguin Books, 2005.

- Pulpit Commentary. Edited by Rev. Joseph S. Exell and Henry Donald Maurice Spence-Jones. Online at BibleHub. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/pulpit/exodus/28.htm. Consulted April 2, 2022.

- Rancière, Jacques. [1969]. The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation. Translated by Kristin Ross. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991.

- Redding, Otis. Complete & Unbelievable: The Otis Redding Dictionary of Soul. Cover artwork Ronnie Stoots. Atlantic, 1966.

- —. “My Girl.” Live on Ready Steady Go. London: BBC, 1966. Viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-dVU3JYcQS0&t=30s . Consulted February 24, 2022.

- —. Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul. Atco Records, 1965.

- Rodney, Walter. The Groundings with My Brothers. Edited by Asha T. Rodney and Jesse J. Benjamin. London and New York: Verso, 2019.

- Stanley, Jason. How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. With a New Preface. New York: Random House, 2020.

- —. “America is now in fascism’s legal phase.” The Guardian. December 21, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/dec/22/america-fascism-legal-phase Consulted April 11, 2022.

- Villaverde, David Joez. “Discomposition: An Interview with Fred Moten.” Michigan Quarterly Review 63.1. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/mqr/2024/03/discomposition-an-interview-with-fred-moten/ Consulted March 30, 2024.

- Wohlfarth, Irving. “History, Literature and the Text: The Case of Walter Benjamin.” Modern Language Notes 96.5, Comparative Literature. December 1981. 1002-1014.

- Wordsworth, William. “Sonnet: To Toussaint L’Ouverture” in William Wordsworth, The Complete Poetical Works of Wordsworth, ed. Henry Reed. Philadelphia: Troutman & Hayes, 1851.

- Zalamea, Fernando. Synthetic Philosophy of Contemporary Mathematics. Translated by Zachary Luke Fraser. Falmouth: Urbanomic. 2019.

- —. [Anonymous]. “Wittgenstein Sheaves.” Glass Bead Research Platform. https://www.glass-bead.org/research-platform/wittgenstein-sheaves/?lang=enview# Consulted January 23, 2022.