Lacey Schauwecker

University of Southern California

Volume 10, 2016

I. Introduction

In colloquial Spanish, tengo que gritarlo [I must scream it] conveys urgency: the need to amplify one’s voice in order to be heard, understood, and solicit a desired response. A literal scream, after all, is both audible and legible to those who indeed respond. Yet, within the testimonio debates of postwar Guatemala, the first-person immediacy of tengo que gritarlo takes on layered, figurative meanings which are not as easily—as literally—legible as one might assume from their generic context: that of historical witnessing, or testimonio. Testimonio as a genre emerged near the end of Guatemala’s 36-year-long civil war (1960-1996), during which President José Efraín Ríos Montt waged a scorched earth campaign against indigenous populations. Since then, the genre has come to be associated with human rights politics and their epistemological frameworks, the objective of which is to secure the legal recognition of past atrocities committed by abusive governments across Latin America, including genocide in Guatemala. Like legal testimony, testimonio is not a genre that accepts the intrusion of figurative language readily—before the law, a scream must be a literal scream, a horror of historical fact. But witnessing is never a simple transmission of the “what happened”, of an abstract provable history. Within Guatemalan testimonio, tengo que gritarlo works at this intersection of the legal and the literary, the legible and the illegible, to open up new readings of testimonio’s representations of violence through literary and photographic metaphor.

John Beverley, the first U.S. scholar to define testimonio as a genre, calls it a “novel or novella-length narrative,” further describing its contours as, “first-person,” “real,” “significant,” and yet “protean” (31). Regarding the literary quality of this genre, he remains undecided. In “The Margin at the Center,” he wavers between testimonio as “a new form of literature… in which we can witness and be part of the emerging culture of an international/popular-democratic subject” and testimonio as necessarily non-literary, insofar as “literature, even where it is infused with popular-democratic form and content… is not itself a popular-democratic cultural form” (43). Though Beverley recognizes literature’s capacity to give voice to victims of violence, sharing subaltern histories and promulgating related politics, he cannot ignore its own exclusionary history. Suspicious of literature as a bourgeois institution with hegemonic politics, he declares the end of testimonio in “The Real Thing,” insisting “that new forms of political imagination and organization are needed; that, as in everything else in life, we have to move on” (78). Toward where might readers and witnesses start moving? Contradicting himself, Beverley tries to offer some direction by deferring to Rigoberta Menchú, a Mayan survivor of Guatemala’s civil war who co-authored Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú y así me nació la conciencia, which is Beverley’s choice model for testimonio. Paraphrasing an interview with her, he stresses how she has considered revising her own testimonio but, deciding it to be “beside the point,” now “has other things she needs or wants to do, which include writing conventionally literary poems in Spanish” (78).

Menchú, in other words, is moving on, to literature. Rather than support Beverley’s assertion that testimonio’s historical and political relevance has expired, his reference to Menchú prompts a reconsideration of the genre’s literary quality. Why does Menchú, herself a genocide survivor and prominent human rights activist, still privilege literature as a viable form of witnessing? Beverley does not reveal Menchú’s reasoning, yet her insistence upon the very literariness of witnessing resists his imperative to “move on,” pointing to a practice of testimonio that is already beyond the confines of literature understood as a bourgeois, hegemonic institution. This practice does not rely upon the epistemological and temporal closure that Beverley proposes, wishing to discard testimonio as now impertinent. In addition to preventing Beverley from making a satisfactory argument, Menchú’s turn toward poetry challenges human rights politics’ similar call for progressive movement. Like Beverley’s understanding of testimonio, these politics ultimately uphold literal truth and linear history as most important to witnessing past atrocities as indeed past. While these politics are critical to indicting perpetrators and securing legal justice, their practice of witnessing is limited by a call for closure that complies with neoliberal logic. Many postwar governments eager to implement neoliberal economic policies including unregulated enterprise and privatized social services, for example, justify amnesty and impunity upon the same premise that epistemological and temporal closure is necessary to political development. For neoliberalism, such closure facilitates historical oblivion, not memory.

Though Beverley, human rights discourse, and neoliberalism justify their calls to move on with varied politics, they commonly neglect the unresolved issue of testimonio’s literariness. Building off of Beverley’s groundbreaking work, however, multiple scholars have reopened this issue in order to defend the genre’s ongoing historical and political relevance. Louise Detwiler and Janis Breckenridge acknowledge the importance of Beverley’s initial definition of “testimonio as a distinctive genre worthy of literary attention,” yet suggest his understanding of literature to be too finite (41). As they state, “it is time for testimonio de jure of scholarship to move forward because testimonio de facto on the ground has undergone a profound metamorphosis” (1-2). For them, literature understood strictly as a historical institution does not account for the multimedia forms of witnessing that testimonio now includes. Rather than move away from the genre as indeed literary, Detwiler and Breckenridge expand such literariness, stretching it “from text to textiles, radio and graphic art; from transcribed to written to spoken, public and performative, and from nonfiction to fiction and film” (2).

In a similar vein, Cynthia Milton turns her attention to testimonio as art more broadly conceived, which she claims to be “less tethered” to literal truth (22). Noting how “literary, visual, oral, and performance arts” enact a witnessing that draws others “toward the unknown,” she distinguishes her project’s multimedia archive from that of human rights politics, which consists of testimonies collected through more “official” processes such as truth commissions and legal trials (3). Though this multimedia testimonio seems more available to interpretation, Milton claims it introduces the unknown in order to ultimately provide new knowledge, eliciting emotional and intellectual responses of “empathy” and “understanding” (22). As such, her project complements, not contradicts, human rights’ privileging of epistemological closure. Elsewhere, Hans Fernández Benítez affirms the need for “una episteme testimonial renovada… que no se agote en categorías y conceptos monolíticos de análisis” [a renovated testimonial episteme… that is not exhausted by monolithic categories and concepts of analysis], yet similarly insists that such an episteme “siga promoviendo una conciencia y solidaridad internacional a favor de los derechos humanos en el ‘Tercer Mundo’” [continues promoting international consciousness and solidarity in support of human rights in the ‘Third World’] (67). While these scholars do take seriously the additional forms that testimonio has taken, redefining its literariness to include multimedia art, none of them consider the radical implications of these redefinitions. I maintain that accounting for literature as a multimedia logic inherent to all language, including the verbal and the visual, reveals interruptive understandings of truth and temporality, as well as history and politics.

Literature, according to Jacques Derrida, does not belong to an exclusionary institution but to logics of figuration and iteration that continually open meaning, as well as historical and political relevance. In “This Strange Institution Called Literature,” an interview between himself and Derek Attridge, Derrida describes literature as “an institution which tends to overflow the institution” (36). A philosopher with a keen interest in literature, Derrida recalls asking himself “What is literature?” and realizing that literature is both “a historical institution with its conventions, rules, etc.” and an “institution of fiction” (37). The latter institution does not subject writers and readers to power but, on the contrary, “gives in principle the power to say everything, to break free of the rules, to displace them” (37). Such power inheres not just in fiction but in all language as a system of figures, or what Derrida also calls traces and marks, that are never literal insofar as they never settle on a single definition or absolute context. As he explains, “The ‘power’ that language is capable of… is that a singular mark should also be repeatable, iterable, as mark. It then begins to differ from itself sufficiently” (43). A mark must be a repeatable mark in order to be legible at all, continually moving onto new contexts of reading and writing and, in doing so, also undergoing interpretive change. Nobody writes, reads, or witnesses in exactly the same way, which makes every mark so dynamic as to overflow its own meaning, become a metaphor of itself.

This definition of literature as a figurative and iterative logic inherent to all language challenges Beverley’s understanding of testimonio, as well as his and human rights discourse’s insistence upon epistemological and temporal closure. Rather than partake of progressive movement within the context of historical witnessing, this logic renders all truth necessarily open to repeating itself and, in doing so, also differing from itself. Accordingly, truth is never simply provable, and the past is never entirely past. While this literary understanding of witnessing cannot convincingly evidence President José Efraín Ríos Montt’s intention to systematically kill Guatemala’s indigenous populations, it can redefine testimonio as a genre even more, rendering it historically and politically relevant insofar as it resists imperatives to move on. Interrupting human rights politics and neoliberalism with representations of violence that cannot be remembered or forgotten absolutely, this literary iteration of testimonio instead demands to be read and re-read, witnessed and re-witnessed.

Returning to Rigoberta Menchú as a survivor-witness and key influence upon Beverley’s conceptualization of the genre, for example, scholars re-read Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú with a focus on her figure of secrets. Throughout her testimonio, Menchú claims her “secretos” [secrets] to symbolize the truths that she cannot share, remaining necessarily unknown to her readers.[1] According to Alberto Moreiras, such secrecy represents “whatever cannot and should not be reabsorbed into the literary-representational system,” withholding truth absolutely (127). As such, her secrets function as a part of literature that is also beyond literature, thereby figuring Derrida’s understanding of literature as an institution that overflows itself. Likewise, Brett Levinson notes how Menchú uses the trope of secrecy to locate her “ideal locus of enunciation” in her deceased “ancestors,” representing voices that can no longer be spoken or heard in a literal way (164). Yet, as interesting and important as these literary readings of testimonio are, neither of them pays specific attention to the “repeatable, iterable” implications of the genre’s literariness (“Strange” 43).

In the aftermath of testimonio’s alleged obsolescence, I recognize screaming as a literary figure that recontextualizes and repurposes the genre, showing it to entail multimedia witnessing that temporarily interrupts human rights politics and related calls to move on. Screaming, as trope, throws into question the boundaries of testimonio, demanding that we re-open firm generic and institutional definitions in order to consider testimonio, again. I trace this trope through Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Insensatez [Senselessness] and Daniel Hernández-Salazar’s “Para que todos lo sepan” [“So that all shall know”], a novel and a photo series about violence in postwar Guatemala, scaffolding my readings with Derrida’s concept of testimonial madness, and Walter Benjamin’s of monadic time. While Insensatez and “Para que todos lo sepan” differ in their allegiance to human rights epistemologies, both involve figurative and iterative screaming that foregrounds testimonio’s literary logic, representing truth, history, and politics through repetition that resists closure. This witnessing beyond testimonio’s original boundaries refuses to substantiate itself in literal language or progressive notions of history.

II. Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Insensatez

As a novel, Insensatez is an overtly literary take on a historical and political moment: the time between the end of Guatemala’s civil war in 1996 and the assassination of Bishop Juan Gerardi, the leader of the Archbishop’s Office of Human Rights (ODHA), in 1998. It was a time of fragile hope, largely dependent upon ODHA’s collection of testimonial and forensic evidence proving the Guatemalan state’s numerous human rights abuses during the war, including but not limited to its genocidal scorched earth campaign against indigenous populations. Setting up a situation almost diametrically opposed to Beverley’s resistance to read testimonio as indeed literary, Castellanos Moya writes Insensatez from the position of a copyeditor who cannot help but read more official testimonies as “estupendas literariamente” [stupendously literary] (43). As an employee for ODHA, this nameless protagonist is responsible for reading all of Guatemala: Nunca Más [Guatemala: Never Again], a truth commission report containing thousands of testimonies, on the short deadline of three months (13). He is overwhelmed from the very beginning, but not simply from the workload. “Yo no estoy completo de la mente” [I’m not complete in the mind] is the first report excerpt to disturb him with its pithy language, which he claims to characterize himself and the country at large. Though this editor was not a firsthand victim of violence, he often identifies with witnesses so closely that he even relives their memories with them.

“Para mí recordar, siento que estoy viviendo otra vez” [For me remembering, I feel that I am living again] is another excerpt that strikes the copyeditor. Noting it to be grammatically incorrect, and thus illegible in a literal sense, he understands such illegibility as itself testimonial. As he states, “[la] sintaxis cortada era la constatación de que algo se había quebrado en la psiquis del sobreviviente que la había pronunciado” [the cut syntax was proof that something had broken in the psyche of the survivor who had spoken] (149). Rather than read the testimony’s words as providing epistemological certainty and closure, the editor appeals to such words’ disjunction as an opening onto more literary understandings of truth. For him, the most convincing example of figurative truth within Guatemala: Nunca Más is screaming, which he reads as a recurrent trope for violence that is likewise recurrent. Though the Guatemalan state signed peace accords ending civil war in 1996, he recognizes racial and political violence as still ongoing and, as such, still worthy of witnessing by screaming horror. Near the novel’s beginning, for example, he reads the testimony of a woman who was kidnapped and tortured by the state army during the civil war. This, like all of the testimonies within Insensatez, is an actual excerpt from Guatemala: Nunca Más. In it, the woman describes the experience of being raped by numerous military officials in a room with a radio “so that no one would hear the screams” (Guatemala 153).

While her own torture went unheard, she claims, years later, still hearing that of a fellow prisoner recounting the scene of his castration, she states, “That guy let out a scream that I have never forgotten, a terrible scream” (Guatemala 153). This scream links back into Insensatez for the copyeditor cannot read this woman’s testimony without likewise hearing, or at least imagining, such a scream. Its intensity even makes him leave his office for a breath of fresh air, only to find out that the report’s witness is actually his very coworker, Teresa. Rather than keep seeing her as a “mujer guapa y misteriosa” [beautiful and mysterious woman], he views her as a torture survivor who is effectively screaming inside (107). Lamenting how the memory of this screaming “la despertaría en las noches por el resto de su vida, tal como aseguraba en su testimonio” [would awaken her at night for the rest of her life, as she asserted in her testimony], he resolves to avoid her at all costs, himself unable to bear the sight and sound that her presence arouses (99). Such resolve is part of the editor’s brief and unsuccessful attempt to escape the literary logic of testimonio, which instead compels him to read her account—and remember such screams—again and again.

As the editor fixates on this and other excerpts from Guatemala: Nunca Más, he even copies choice lines into his own journal and repeats them compulsively, all the while showing a critical apathy toward ODHA’s human rights politics. Reciting some lines to his friend Toto, he specifies his objective not as “convencerlo de la bondad de una causa justa” [to convince him of the goodness of a just cause] but rather “mostrarle la riqueza de lenguaje de sus mal llamados compatriotas aborígenes, y ninguna otra cosa más” [to show him the richness of the language of their damned aboriginal compatriots, and nothing else] (32). The richness of this testimonial language inheres in its literary qualities, not literal meanings. The more the editor reads and re-reads the testimonies, the more layered and varied their meanings become. Especially intrigued by the figures and syntax employed by survivor-witnesses speaking in Spanish as their second language, he describes such accounts with terms such as “frases sonoras,” “poesía,” and “musicalidad” [sonorous phrases, poetry, and musicality] (33, 123, 152). This obsession with the auditory aspects of such accounts partially explains the editor’s sensitivity to Teresa’s memory of screaming, which he describes as “un aullido como si el despejo hubiera estado en sus cincos sentidos, el aullido más horrible que la chica hubiera escuchado jamás” [a howl as if the victim had been fully conscious, the most horrendous howl the girl had ever heard] (99). Though Castellanos Moya, by way of the editor, sometimes uses “grito” [scream] and “aullido” [howl] interchangeably, both figures mark the limits of verbal language, dissolving from words into seemingly senseless sound.

Within Insensatez, such senselessness takes on manifold significance. The sound of screaming, at least as recounted by Teresa and re-imagined by the editor, is the sound of life before and after death. Originally emitted by the torture victim upon his castration, such screaming marks the final moments of his life, as well as that which survives him: his memory. This memory lives on in Teresa’s recounting of the what-happened, yet not as a literal and indeed audible scream. Even upon its first iteration—its first re-witnessing—such screaming transforms into the word “grito,” a figure for the sound, that wordless cry of excruciating pain. This figure, now literary, overflows with layered and varied meanings. In the editor’s witnessing of Teresa’s testimony, which is a witnessing of the castrate’s suffering, for example, screaming functions as a metaphor for the editor’s own horror: a horror that compels him to identify with Teresa’s memory so closely that he, like her, continues to hear “el aullido más horrible” [the most horrendous howl] (99). Eventually, the editor even emits his own scream, or howl, which Castellanos Moya likewise figures beyond the limits of verbal language and literal sense. Fearful that his involvement with ODHA has put his own life in danger amid ongoing violence within postwar Guatemala, the editor flees the city for a rural retreat center, where he hopes to ease the anxiety that has heightened while reading the testimonies. Still fixating on particular lines and paranoid about his own persecution once there, however, he claims, “mi mente se me fue de las manos y no tuve ya momento de sosiego” [my mind went out of control and I no longer had any relief], thereafter exiting to a patio in order to “aullar como un animal enfermo bajo el cielo estrellado” [howl like a sick animal under the starry sky] (139).

This is the precise moment that multiple critics recognize as the copyeditor’s own psychotic break. Nanci Buiza and Misha Kokotovic call it a moment of “trauma” and “edge of insanity,” respectively, while Christian Kroll-Bryce suggests it to demonstrate a “reasonable senselessness” appropriate for the chaotic violence still dominant within an increasingly neoliberal postwar Guatemala (Buiza 164, Kokotovic 560, Kroll-Bryce 392). That Teresa and the protagonist continue to hear the screaming of fellow victims who, unlike them, did not survive the war, also situates such screaming as a figure for what Derrida describes more generally as the “madness” inherent to all testimony and witnessing. In Demeure: Fiction and Testimony, a critical essay on Maurice Blanchot’s short story titled “The Instant of My Death,” Derrida explains how testimony is structured by the condition that one survives whatever experience to which one subsequently bears witness. Humans must live to tell, but such telling is always incomplete because one can only bear witness to death if one does not, in fact, experience it. This logic of survival situates truth beyond epistemological and temporal closure.

Reading Blanchot’s text as a semi-autobiographical account of his own encounter with death by a Nazi firing squad, Derrida claims “unexperienced experience” to make all testimony possible yet, as such, also inseparable from the possibility of fiction, or indeed literature (54). Pointing out how survivors only can testify to events that they did not fully experience and, as a result, might indeed recount erroneously, he states,

The possibility of literary fiction haunts so-called truthful, responsible, serious, real testimony as its proper possibility. . . The testimony testifies to nothing less than the instant of an interruption of time and history, a second of interruption in which fiction and testimony find their common resource.

(73)

It testifies, in other words, to an interruption that simultaneously founds and incompletes time, history, and the possibility of witnessing. Arguing against institutional demands for testimonies to be articulate and coherent not only temporally, but also epistemologically, Derrida claims such standards to “rely on a naïve concept of testimony, requiring a narrative of common sense when its madness is put to the test of the impossible” (48). This madness is the constitutive possibility of literary fiction, which legal trials and associated human rights politics nevertheless put to the impossible test of provability.

By foregrounding the literary quality of testimony, Derrida helps justify the editor’s rejection of ODHA’s human rights politics, as well as more general imperatives for literal legibility. By the time we get to the scene in which the editor himself howls like a sick animal, however, most readers of Insensatez have given up on him as a reliable narrator and witness, instead considering him to be a paranoid drunk. Ignacio Sánchez-Prado, for example, claims that Insensatez demonstrates a recent “post-testimonial” tendency of Central American authors to reclaim writing, both fiction and non-fiction, from the stronghold of testimonio’s political and ethical “imperatives” (82). That the editor ultimately abandons his role with ODHA and associated human rights efforts causes Sánchez-Prado to dismiss historical memory within Insensatez as not “redemptive” but “futile” (85). Sánchez-Prado suggests historical memory to be futile here because it fails to witness past violence in a way that facilitates moving on, either from the part of the protagonist or Guatemala more generally. Yet such failure, as I have been suggesting, also can be witnessed as evidential of testimonio’s ongoing historical and political relevance. Because Teresa and the editor do not situate memories of violence as indeed past, for example, their iterative screaming continually interrupts human rights politics, exposing the impossibility of epistemological or temporal closure.

As truthful as the literary figure of screaming may be, it remains more commonly interpreted as senselessness, which upsets Insensatez’s copyeditor protagonist. In another reading of Guatemala: Nunca Más, he critiques a psychiatric doctor’s writing for being so “aséptico” [aseptic] as to diagnose victims’ mental conditions without actually engaging the madness inherent to their testimonies (27). Such madness, according to the report’s editor, is in both form and content. In addition to recognizing testimonio as a genre structured by survival, and thus the impossibility of literal legibility, he understands screaming as an interruptive figure demanding more literary interpretations. Moved by the story of a deaf-mute who was tortured to death, for example, he questions the sanity and authority of “un sargento bastante bruto si consideramos que destazó al mudito sin darse cuenta de que esos gritos no eran sólo de dolor, sino de un mudito para quien ésa era su única forma de expression” [a brute sergeant who murdered the little mute boy without realizing that those screams were not only of pain, but of a little mute boy’s only form of expression] (29). In this instance, screaming stands in for language while also signifying beyond it. Here, screaming is the mute’s language, which he employs to confess his own truth. Because this truth exceeds epistemological frameworks for truth, however, the sergeant fails to witness it as such.

Throughout Insensatez, the editor critiques military leaders, leftist leaders, and human rights activists alike for failing to witness violence in an interruptive and politically relevant way. Disgusted by leftist poetry written on the walls of a Guatemalan bar-café, he claims that literary excerpts from Guatemala: Nunca Más should replace those “horribles versos de mediocres poetas izquierdistas vendedores de esperanza” [horrible verses written by mediocre poets, sellers of hope] (41). Though the editor’s dismissal of leftist and human rights politics may appear to be cynical, Castellanos Moya ultimately suggests this protagonist to be both paranoid and perceptive. Near the novel’s end, he receives an email informing him that Bishop Gerardi, the leader of ODHA, was brutally assassinated by state officials just three days after presenting a completed Guatemala: Nunca Más to the public, thereby partially justifying the copyeditor’s disillusionment with human rights discourse. For the editor, this discourse’s axiom that truth can guarantee justice is at odds with the figurative and iterative nature of testimonio, as well as ongoing violence within postwar Guatemala.

As an actual, not fictional, employee for ODHA, however, photographer Daniel Hernández-Salazar is more committed to human rights politics’ “causa justa” [just cause] than Insensatez’s protagonist. Rather than flee Guatemala, this witness insists upon the importance of Guatemala: Nunca Más in documenting, protesting and ending his nation’s history of violence. Indeed, he maintains such insistence both before and long after Bishop Gerardi’s historical assassination. In this sense, he exhibits an unwavering belief in provable truth and linear history that his own work ends up undermining or, more specifically, that his own photos of screaming angels end up interrupting. Additionally, his angel-witnesses show seemingly non-literary modes of testimonio, such as photography, to be likewise iterative, overflowing with varied meanings. Against the artist’s own human rights politics, such screaming furthers my claim that testimonio’s literariness entails a multimedia epistemology that resists imperatives for closure and progress.

III. Daniel Hernández-Salazar’s “Para que todos lo sepan”

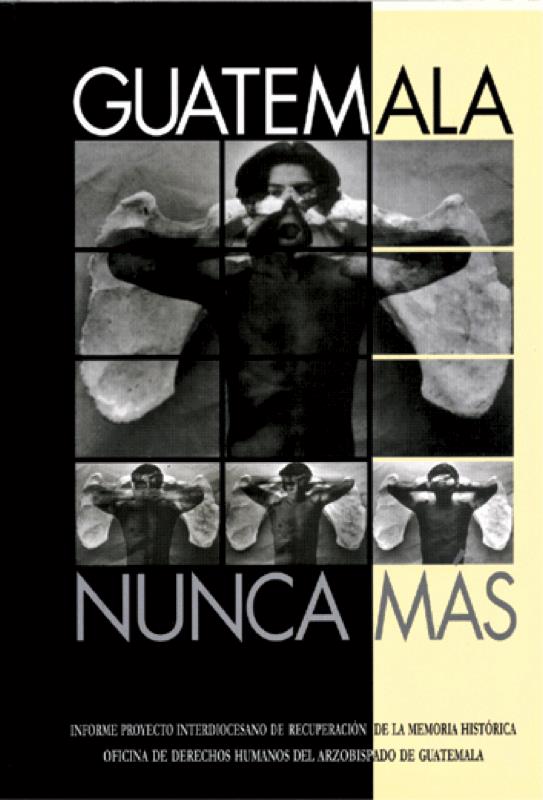

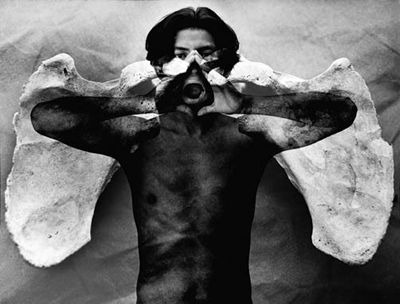

Working as a photojournalist and participant in mass grave exhumations when ODHA commissioned him to create its cover image, Hernández-Salazar combined bones from such exhumations with the more ambiguous figure of a screaming angel. At the time, however, the photographer did not understand such an image, titled “Esclarecimiento” [Clarification], as ambiguous at all. On the contrary, he saw it as proof of the Guatemalan genocide that would prove the past in related legal trials, thereby enabling historical progress. Indeed, it would replace amnesia with mourning, and impunity with justice. For this reason, “Esclarecimiento” consists of four images, each of the same angel as he covers his ears, eyes, and mouth before ultimately cupping his mouth and screaming (see Figs. 1 and 2.). According to the artist, this screaming angel, which he calls “Para que todos lo sepan” [So that all shall know], “es justamente el angel que rompe el silencio que los otros tres [ángeles] denunciaban. Lo hice porque la ODHA con su informe acerca de las violaciones [de los derechos humanos] iba a romper el silencio” [is precisely the angel that breaks the silence that the other three [angels] denounced. I made it because ODHA, with its reporting about the [human rights] violations was going to break the silence] (Palabra).

Breaking such silence is necessary for curing the sickness with which Hernández-Salazar diagnoses Guatemalan society: “esa misma sociedad a la que no le gusta ver y oír lo que sucede y que está acostumbrada a callar” [the same society that does not like to see or hear what happens and that is accustomed to shutting up] (“Asi”). This sickness, according to the photographer, is one of “injusticia, intolerancia, violencia” [injustice, intolerance, violence] (Palabra). That Guatemala: Nunca Más “was going to break the silence,” however, renders such an action incomplete, bound to iteration. Even though Hernández-Salazar has recreated his screaming angel amid ongoing impunity for President José Efraín Ríos Montt and other state criminals within Guatemala, for example, none of his adaptations break silence in any resounding or progressive way. Instead, they resignify such screaming as silently shocking, iterative, and interruptive.

The first adaptation of “Para que todos lo sepan” was not created by the artist himself but fellow witnesses. The day after Bishop Gerardi’s assassination, hundreds of Guatemalans silently marched through the capital city wielding enlarged posters of Hernández-Salazar’s “Esclarecimiento” and the titular, emphatically capitalized “GUATEMALA: NUNCA MÁS” (see Fig. 3.).

This message of “never again” was literally and figuratively muted in this context, for protestors were gathering to denounce yet another instance of state violence, this time nearly two years after the signing of civil war peace accords. Yet, instead of simply shutting up, these Guatemalan protestors were publicly refusing to cover their eyes, ears, and mouths. With “Para que todos lo sepan,” they were silently screaming in order to witness violence: violence, however, that clearly was not as past as their “never again” message proclaimed. Yet what, exactly, might the screaming make known this time: Yes, there was a murder? Yes, there is still impunity for genocide and other human rights violations? Never again, again? Surprised to see such street protesters brandishing his work, Hernández-Salazar rushed home to retrieve his camera. In his words, “When I saw that, I immediately understood that I had to take photos; I had to follow what could happen with the pictures” (Mackenzie 20).

Indeed, he had to follow, as well as create, another series of screams. When the anniversary of the Bishop’s assassination approached with its perpetrators still benefitting from impunity, Hernández-Salazar again recreated “Para que todos lo sepan.” As he explains, “Los años pasan. Se apilan como páginas de un libro. Todo queda impune. Tengo que gritarlo” [Years pass. They peel away like pages in a book. Everything remains unpunished. I must scream it] (So that 1). The night before the assassination’s anniversary, Hernández-Salazar installed dozens of enlarged angels throughout Guatemala City. Installation sites included Bishop Gerardi’s parish, military intelligence facilities, army headquarters, military barracks, the presidential guard facilities, and a former military school. Some sites immediately recognized and removed the denunciatory angel. Others, including various military sites, did not understand the image’s significance until a local newspaper published an article explaining its connection to ODHA a few days later (Hoelscher 213).

Aside from being much larger and cut into squares in order to facilitate fast and clandestine mounting, this angel series is identical to “Para que todos lo sepan” (see Fig. 4.). Appearing to intentionally differentiate it, however, Hernández-Salazar has referred to this series specifically as “Ángel callejero” [Street Angel] and “El ángel que grita justicia” [The angel that screams justice] (“Así”). While the photographer considers all his work to be part of human rights politics, he further distinguishes the screaming of “Ángel callejero” to be more target-specific, and yet also more ambiguous. Noting his decision not to include the written message of “Guatemala: Nunca Más” with these public installations, he states, “la imagen ya estaba muy fija en la mente del público a través de los libros y los periódicos que la publicaron. Se dejó mejor un poco ambiguo para que sea más misterioso y más cuestionadora a las personas” [the image was already fixed in the public’s minds from the books and newspapers that published it. It was better to leave it a little ambiguous so that it would be more mysterious and interrogative for people] (Palabra). Here, Hernández-Salazar acknowledges the reproduction, or indeed iteration, of his screaming angels to introduce varied meanings. In doing so, he also foregrounds the literariness of such photography, inadvertently suggesting it to be testimonio that resists epistemological and temporal closure.

Though this resistance is at odds with the photographer’s commitment to ODHA and its political aims of proving truths and moving on, reading Hernández-Salazar’s screaming angel against Walter Benjamin’s concept of monadic time opens up a new way to consider the iterative temporality of the angel. In “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Benjamin uses Paul Klee’s “Angelus Novus,” a painting of an angel likewise facing forward with an open mouth and eyes, in order to propose a mode of witnessing that is less progressive than that upheld by human rights politics. According to Benjamin, this “Angel of History” is facing the past, which he does not see as a linear “chain of events” but the repetition of “one single catastrophe,” namely violence committed by what he calls history’s “victor[s]” (256, 257). While this angel wishes to witness this violence as also part of the present, “progress” pulls him forward, urging him to focus exclusively on the future instead of witnessing a more monadic, and indeed truthful, understanding of time (256).

Contrary to human rights efforts seeking to resolve the past as a way of righting the present and enabling a better future, Benjamin positions his open-mouthed angel as calling for an understanding of history in which “time stands still and has come to a stop” (262). To witness this arrest of time, according to Benjamin and his philosophy of historical materialism, means “to take control of a memory” when it is at greatest risk of being appropriated by advocates of progress and instead recognize its internal “tensions” as “the sign of a messianic cessation of happening, or put differently, a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past” (262). For Benjamin, such cessation of happening is both messianic and revolutionary because it includes the past, present, and future all at once: compressed into a monad that challenges the very advancement of time, as well as the political movements either ruthlessly enforcing or more benevolently advocating it.

While Hernández-Salazar’s “Ángel callejero” may seem to advance ODHA’s mission of proclaiming the particular truth of violence and impunity, its ambiguities simultaneously function like Benjamin’s temporal tensions insofar as they resist comprehension and, in this sense, any sort of restitution or progression. Benjamin’s “Angel of History” would like to “make whole what has been smashed,” yet he cannot precisely because it is still being smashed or, stated otherwise, the past is the present (257). To witness this history instead requires pause, which Hernández-Salazar also elicits with his images. In addition to installing “Ángel callejero” in “lugares muy visibles y símbolicos” [very visible and symbolic places], the photographer also sought sites “donde habían semáforos [y] la gente tiene que esperar unos minutos” [where there were streetlights [and] people had to wait some minutes] (Palabra). Indeed, they had to wait and contemplate these images just enough to experience a defamiliarizing retake, for they were once again being faced by the very angel that originally meant to end violence in Guatemala.

Likewise recognizing a mutual resonance between Hernández-Salazar’s photos and Benjamin’s ideas, historian Stephen Hoelscher claims the mechanical reproduction of “Para que todos lo sepan” and “Ángel callejero” to enhance “the aura of the original,” suggesting iteration to bolster, not interrupt, the artist’s human rights politics (Hoelscher 213). Though Hoelscher perceptively observes Hernández-Salazar’s angels to foreground a political struggle over historical memory, he overlooks how “Ángel callejero” appears and disappears in a way that diminishes whatever auratic quality it, or any memory, may have once had. Pointing to an angel that he positioned under a highway underpass so that cars’ lights would hit it as they passed, for example, Hernández-Salazar emphasizes the angel’s interruptive and fleeting presence as integral to its truth value. In his words, “Allá abajo es como un refugio: un lugar oscuro donde está escondido…esconderse, estar abajo, guarderse del peligro… [y] cuando lo veías, pasaba muy rápido… era muy fugaz” [There, underneath, is like a refuge: a dark place where the angel hides… protecting himself from danger… [and] when you saw it, it passed very quickly… it was very fleeting] (Palabra). Rather than measure the truth value of this angel based primarily upon presence, as art does with “aura” and human rights efforts do with material and testimonial evidence, Hernández-Salazar’s work connects truth value with shock value.

Benjamin makes this same connection while situating his “Angel of History” as a figure for monadic time and associated historical materialism. Rejecting history that is written in the name of progress, Benjamin instead proposes one that is experienced as shock. Elaborating upon the aforementioned moment in which “thinking suddenly halts in a constellation overflowing with tensions,” he claims “there it yields a shock to the same, through which it crystallizes as a monad” (263). This monad, containing “revolutionary” and “messianic” potential, can then “blast a specific era out of the homogenous course of history” and, in doing so, reveal history as instead interruptive and inconclusive (263). While the continual iterations of Hernández-Salazar’s “Para que todos lo sepan” may seem to suggest a certain inefficacy if measured in relation to their original purpose of making the Guatemalan genocide known, both publicly and legally, they are actually accurate and necessary in this Benjaminian sense. As long as history remains at risk of being decided as indeed past, either in the name of neoliberal amnesia or legal justice, Hernández-Salazar’s screaming angels remain politically urgent reminders of this very impossibility.

Yet, later versions of “Ángel callejero” bear an explicit articulation of the message, “Sí hubo genocidio.” Hernández-Salazar posted these installations in May of 2013, shortly after Guatemala’s congress overturned a brief court conviction of President José Efraín Ríos Montt for charges of genocide. Such a ruling would have been the first domestic conviction of a former Latin American dictator but, in a regressive change of events, Guatemala thereafter began debating whether genocide happened at all. As necessary as the public affirmation of “Sí hubo genocidio” may be, the claim’s preterite phrasing is still incongruous with the photograph’s iterative history. Though the original “Para que todos lo sepan” was created with the specific purpose of making genocide legally known and, in this sense, officially past, such a message appears both insufficient and inaccurate within the context of ongoing state violence, impunity, and human rights politics. Rather than work toward achieving Hernández-Salazar’s original mission, these screaming angels more convincingly display what Rebecca Schneider calls “the curious inadequacies of the copy” or, as Derrida explains, the curious way in which every mark “differ[s] from itself slightly” (Schneider 6, “Strange” 43). According to Schneider, the practice of reenacting “a precedent event, artwork, or act,” which Hernández-Salazar does with “Para que todos lo sepan” and “Ángel Callejero,” troubles investments in “straightforward linearity as the only way to mark time… and points to a politic in veering, revolving, turning around, reappearing” (182). This politic, as I have been arguing throughout my reconsideration of testimonio, acknowledges truth as literary and, as such, subject to figuration and iteration. Within Guatemalan testimonio, such iteration also attests to the country’s historical logic wherein war-related violence, including the assassination of Bishop Gerardi, continues repeating in the postwar era.[2]

IV. Conclusion

As invested as Hernández-Salazar remains in human rights efforts to separate the present from the past, and postwar from war, in order to declare “Sí hubo genocidio,” Schneider’s reproduction of the “Nunca más” message resonates with this photographer’s images. In Schneider’s words, “the time to protest is Now. It is Again. It is the necessary vigilance, the hard labor, of reiterating Nunca Más, Never Again. Never, Again. And, now, again” (186). This, effectively, is what Hernández-Salazar’s screaming angels make known. The interrupted yet insistent repetition of “never again” is also reminiscent of Insensatez’s protagonist and his compulsive recitation of testimonial excerpts. Because photography and all language are, as Derrida claims, “repeatable, iterable” in a way that causes them to differ from themselves, they are structured by the same possibility of non-truth or, more appropriately, a reconfigured type of truth (“Strange” 43). While Hernández-Salazar does not intentionally participate in such reconfiguration, continually appealing to legal authorities for recognition based on their understandings of literal truth and linear history, his work functions as testimonio insofar as it indeed fails. By failing to achieve such recognition, instead being misunderstood or destroyed by state institutions, his screaming angels function more like Benjamin’s “Angel of History”: an angel that speaks in a screaming silence, and does so over and over again.

Rather than partake of the very logic of moving on, which testimonio, neoliberalism, and human rights politics together uphold, Castellanos Moya’s novel and Hernández-Salazar’s images, with their iterations, alternatively work to reimagine history in a way that “loosen[s] the habit of linear time” (Schneider 19). Such imagination is not one of “the new forms of political imagination and organization” that Beverley anticipated, let alone acknowledged as possible, when foreclosing testimonio as a historically and politically relevant genre (78). While human rights politics continue appealing to the very institutions that refuse to verify their truths, screaming as witnessing foregrounds a testimonio that instead appeals to not deciding: not deciding on truth as provable, time as progressive, nor the testimonio genre as obsolete.

Notes

01. She ends Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú with the claim, “Sigo ocultando lo que yo considero que nadie sabe… ni un intelectual, por más que tenga muchos libros, no sabe distinguir nuestros secretos” [I continue hiding that which I consider nobody shall know… not even an intellectual, with his many books, knows how to distinguish our secrets” (271).

02. In 2001, three army officers were convicted of committing Gerardi’s assassination. This trial marked the first time that members of the Guatemalan military were tried in a civilian court.

Works Cited

- Beverley, John. Testimonio: On the Politics of Truth. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

- Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Shocken Books, 2007.

- Castellanos Moya, Horacio. Insensatez. Barcelona: Tusquets Editores, 2005.

- Buiza, Nanci. “Trauma and the Poetics of Affect in Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Insensatez.” Revista de Estudios Hispánicos 47.1 (2013): 151-72.

- Derrida, Jacques. Demeure: Fiction and Testimony. Trans. Elizabeth Rottenberg. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Derrida, Jacques. “‘This Strange Institution Called Literature’: An Interview with Jacques Derrida.” Acts of Literature. Ed. Derrick Attridge. London: Routledge, 1992. 33-75.

- Detwiler, Louise and Janis Breckenridge. Eds. Pushing the Boundaries of Latin American Testimony: Meta-morphoses and Migrations. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Fernández Benítez, Hans. “‘The Moment of Testimonio is Over’: problemas teóricos y perspectivas de los estudios testimoniales.” Íkala 15 (2010): 47-71.

- Guatemala, Never Again!: Recovery of Historical Memory Project. Human Rights Office, Archdiocese of Guatemala. New York: Orbis Books, 1999.

- Hernández–Salazar, Daniel. “Así me convertí en Daniel Hernández–Salazar.” ContraPoder. Web. 31 Dec. 2014. <http://www.contrapoder.com.gt/es/edicion7/actualidad/337/>

- — — —. So that all shall know. Ed. Oscar Iván Maldonado. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007.

- Hoelscher, Steven. “Angels of Memory: Photography and Haunting in Guatemala City.” GeoJournal 73 (2008): 195-217.

- Kokotovic, Misha. “Testimonio Once Removed: Castellanos Moya’s Insensatez.” Revista de

- Estudios Hispánicos 43.3 (2009): 545-562.

- Kroll-Bryce, Christian. “A Reasonable Senselessness: Madness, Sovereignty and Neoliberal Reason in Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Insensatez.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 23.4 (2014): 381-399.

- La Palabra Desenterrada. Dir. Mary Ellen Davis. 2001. Film.

- Levinson, Brett. The Ends of Literature: The Latin American ‘Boom’ in the Neoliberal Marketplace. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002.

- Menchú, Rigoberta. Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú y así me nació la conciencia. México D.F.: Siglo XXI Editores, 1985.

- Milton, Cynthia. Ed. Art from a Fractured Past: Memory and Truth-Telling in Post-Shining Path Peru. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2014

- Moreiras, Alberto. The Exhaustion of Difference: The Politics of Latin American Cultural Studies. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2001.

- Sánchez-Prado, Ignacio M. “La ficción y el momento de peligro: Insensatez de Horacio Castellanos Moya.” Cuaderno Internacional de Estudios Humanisticos y Literatura. 14 (2010): 79-86.

- Schneider, Rebecca. Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment. London and New York: Routledge, 2011.